But why should we learn about the world and its history, why bother trying to live in harmony with others? What is the point of all this effort? And does it have to make sense? These questions, and some others of a similar nature, bring us to the third dimension of philosophy, which touches upon the ultimate question of salvation or wisdom. If philosophy is the ‘love’ (philo) of ‘wisdom’ (sophia), it is at this point that it must make way for wisdom, which surpasses all philosophical understanding. To be a sage, by definition, is neither to aspire to wisdom or seek the condition of being a sage, but simply to live wisely, contentedly and as freely as possible, having finally overcome the fears sparked in use by our own finiteness. –Luc Ferry in A Brief History of Thought

Mental Models: http://www.farnamstreetblog.com/mental-models/

Why Legos Are So Expensive — And So Popular? Hint—it is a FRANCHISE! (I hope readers who have children that play with Legos can add their input–Why did you shell out those big bucks for plastic blocks?)

January 16, 2013

A lot of people wonder how Lego, selling a now un-patented product, can command both massive market share and sell at twice the price of the nearest competitor: Megablocks.

Mega blocks are much cheaper than Legos yet Legos dominates in sales.

Mega blocks are much cheaper than Legos yet Legos dominates in sales.

Rhett Allain, in his WIRED article addressing why lego sets are so expensive, unsatisfyingly concludes “Honestly, I don’t know much about plastic manufacturing – but the LEGO blocks appear to be created from harder plastic. Maybe this would lead them to maintain their size over a long period of time.”

While lego offers a superior product, that doesn’t wholly account for why they sell so well.

Chana Joffe-Walt offers a much better explanation in her NPR Planet Money article: (click on link to hear the radio show on Legos)

Lego did find a successful way to do something Mega Bloks could not copy: It bought the exclusive rights to Star Wars. If you want to build a Death Star out of plastic blocks, Lego is now your only option.

The Star Wars blocks were wildly successful. So Lego kept going — it licensed Indiana Jones, Winnie the Pooh, Toy Story and Harry Potter.

Sales of these products have been huge for Lego. More important, the experience has taught the company that what kids wanted to do with the blocks was tell stories. Lego makes or licenses the stories they want to tell.

Lego isn’t just selling a product, they are selling a story. Still, I doubt that alone fully explains the difference.

I think Warren Buffett offers the best explanation. Talking about the brand power of See’s Candies, he comments:

What we did know was that they had share of mind in California. There was something special. Every person in Ca. has something in mind about See’s Candy and overwhelmingly it was favorable. They had taken a box on Valentine’s Day to some girl and she had kissed him. If she slapped him, we would have no business. As long as she kisses him, that is what we want in their minds. See’s Candy means getting kissed. If we can get that in the minds of people, we can raise prices. I bought it in 1972, and every year I have raised prices on Dec. 26th, the day after Christmas, because we sell a lot on Christmas. In fact, we will make $60 million this year. We will make $2 per pound on 30 million pounds. Same business, same formulas, same everything–$60 million bucks and it still doesn’t take any capital.

… It is a good business. Think about it a little. Most people do not buy boxed chocolate to consume themselves, they buy them as gifts—somebody’s birthday or more likely it is a holiday. Valentine’s Day is the single biggest day of the year. Christmas is the biggest season by far. Women buy for Christmas and they plan ahead and buy over a two or three-week period. Men buy on Valentine’s Day. They are driving home; we run ads on the Radio. Guilt, guilt, guilt—guys are veering off the highway right and left. They won’t dare go home without a box of Chocolates by the time we get through with them on our radio ads. So that Valentine’s Day is the biggest day.

Can you imagine going home on Valentine’s Day—our See’s Candy is now $11 a pound thanks to my brilliance. And let’s say there is candy available at $6 a pound. Do you really want to walk in on Valentine’s Day and hand—she has all these positive images of See’s Candy over the years—and say, “Honey, this year I took the low bid.” And hand her a box of candy. It just isn’t going to work. So in a sense, there is untapped pricing power—it is not price dependent.

The reason Lego is awesome and Megablocks is not has as much to do with what’s in the consumers’ mind as the product on the shelf. It’s the experience you have with Lego that makes it so amazing.

Remember the first time you played with Lego? You want to pass that experience off to someone else. No one wants to show up to a kid’s birthday party and announce to everyone they took the ‘low bid’ on a relatively cheap children’s toy.

Lego is a safe bet and we want to reduce uncertainty.

Read more posts on Farnam Street on:

Association bias • Lego • Warren Buffett

—

I went to Toys R Us recently to buy my son a Lego set for Hanukkah. Did you know a small box of Legos costs $60? Sixty bucks for 102 plastic blocks!

In fact, I learned, Lego sets can sell for thousands of dollars. And despite these prices, Lego has about 70 percent of the construction-toy market. Why? Why doesn’t some competitor sell plastic blocks for less? Lego’s patents expired a while ago. How hard could it be to make a cheap knockoff?

Luke, a 9-year-old Lego expert, set me straight.

“They pay attention to so much detail,” he said. “I never saw a Lego piece … that couldn’t go together with another one.”

Lego goes to great lengths to make its pieces really, really well, says David Robertson, who is working on a book about Lego.

Inside every Lego brick, there are three numbers, which identify exactly which mold the brick came from and what position it was in in that mold. That way, if there’s a bad brick somewhere, the company can go back and fix the mold.

For decades this is what kept Lego ahead. It’s actually pretty hard to make millions of plastic blocks that all fit together.

But over the past several years, a competitor has emerged: Mega Bloks. Plastic blocks that look just like Legos, snap onto Legos and are often half the price.

So Lego has tried other ways to stay ahead.

The company tried to argue in court that no other company had the legal right to make stacking blocks that look like Legos.

“That didn’t fly,” Robertson says. “Every single country that Lego tried to make that argument in decided against Lego.”

But Lego did find a successful way to do something Mega Bloks could not copy: It bought the exclusive rights to Star Wars. If you want to build a Death Star out of plastic blocks, Lego is now your only option.

The Star Wars blocks were wildly successful. So Lego kept going — it licensed Indiana Jones, Winnie the Pooh, Toy Story and Harry Potter.

Sales of these products have been huge for Lego. More important, the experience has taught the company that what kids wanted to do with the blocks was tell stories. Lego makes or licenses the stories they want to tell.

And kids know the difference.

“If you were talking to a friend you wouldn’t say, ‘Oh my God, I just got a big set of Mega Bloks,’ ” Luke says. “When you say Legos they would probably be like, ‘Awesome can we go to your house and play?’ ”

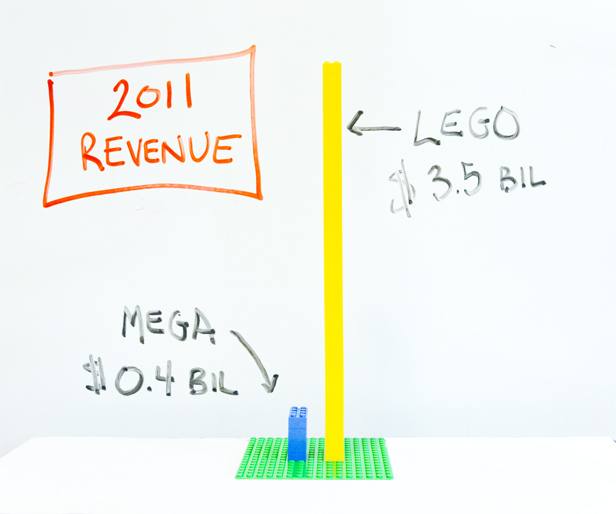

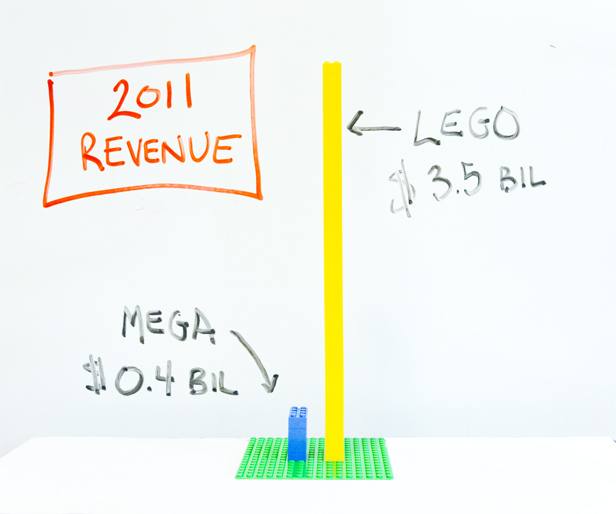

Lego made almost $3.5 billion in revenue last year. Mega made a tenth of that.

But Mega Bloks may yet gain on Lego.

Mega now owns the rights to Thomas the Tank Engine, Hello Kitty, and the video game Halo. And, on shelves for the first time ever this week: Mega Bloks Barbies.

PS: I will post shortly on a Reader’s Question: What besides an Index would you recommend for a person who seeks safety and return on his/her capital?