Buy them when they are up, and sell them when the margin clerk insists on it. It is obviously impossible for the thinking Wall Streeter to avoid acting on that principle. He certainly can’t buy them when they are down, because when the are down “conditions” are terrible. You can ask an experienced Wall Street man to buy stocks when carloadings have just hit a new low and unemployment is at a peak and steel capacity is less than half of normal and a very big man (“of course I can’t tell you his name”) has just informed him in confidence that one of the big underwriting houses in the Middle West is in really serious trouble.

Unfortunately for everyone concerned, these are the only times when stocks are down. When “conditions” are good, the forward-looking investor buys. But when “conditions” are good, stocks are high. Then, without anyone having the courtesy to ring a warning bell, “conditions” get bad. Stocks go down, and the margin clerk sends the forward-looking investor a telegram containing the only piece of financial advice he will ever get from Wall Street which has no ifs or buts in it. (Source: Where Are The Customers’ Yachts? by Fred Schwed, Jr.)

John Hussman (www.hussmanfunds.com)

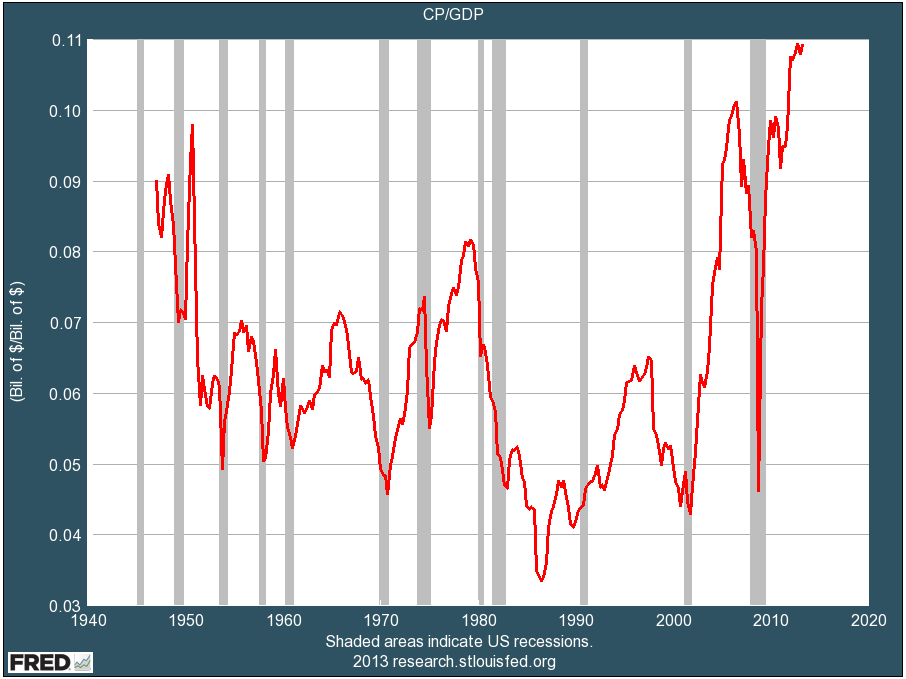

The fact that profits as a share of GDP are more than 70% above their historical norm should immediately raise a question as to whether current year earnings or next year’s projected “forward earnings” should be used as a sufficient statistic for long-term cash flows and equity market valuation without any further reflection. Then again, more work is required to demonstrate that such an approach would be misleading. We’re just getting warmed up.

http://www.hussmanfunds.com/wmc/wmc131125.htm

GMO_QtlyLetter_ALL_3Q2013 Be Careful! Future returns expected to be negative over the next seven years.

Csinvesting: Stocks are probably fairly valued IF long-term bonds were normalized. 4% to 5% is a far cry from 3% in the Ten-year Treasury.

For Whom the Bell Tolls Bob Moriarty Archives Nov 25, 2013

I’ve heard it said that they don’t ring a bell at the top. That’s bullshit, of course. In March of 2000 I read that inmates in a jail in Baltimore were holding stock picking contests. If you wanted to pick the very last group who would ever be likely to participate in a stock market bubble, it would probably have to be inmates in a jail in Baltimore. Ding, ding, ding.

Luckily for the poor prisoners in Baltimore, they can go back to doing drugs, extortion and getting correctional officers pregnant, they don’t have to waste any more time on the stock market. They did ring a bell at that top on March 10, 2000.

They just rang another bell. Only time will tell if it’s a top but I can clearly hear the clanging of a bell.

There are times that you know intuitively that some people have way too many dollars and way too little ‘cents.’ Ten days or so ago, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook offered $3 billion in cash for an application named Snapchat. Snapchat was co-founded by a 23-year-old named Evan Spiegel.

Snapchat is an interesting app that provides a 14-year-old young lady the opportunity to send her 15-year-old boyfriend a nice picture of her budding boobs. She can be secure in knowing that the competitive advantage of Snapchat is that the picture disappears in 1-10 seconds depending on the option of the person using it. Luckily for her boyfriend, he can do an instant save and pass the “sext” around to all his friends. This is known as “sexting” and is a lot more fun than anything I ever did in high school.

Snapchat CEO Evan Spiegel promptly rejected the $3 billion offer despite having no revenues and no business plan but runs a handy application for every 14-year-old.

Somebody is being really flipping stupid. It’s a tossup as to whether it’s Zuckerberg for offering to overpay for an application that anyone could duplicate in a month, or Spiegel for not taking the cash and running for the nearest French beach where all the women will show you their boobs and you don’t need a cellphone to look at them.

You don’t have to be the mayor of Toronto to smoke crack and do really stupid things. Applications come and go. Computers come and go. I can remember when the Trash 80 from Tandy Radio Shack was the hottest computer in the market. Then the IBM PC and AT and PCJr and now Apple. All things change.

Actually I think they are both being dumber than a brick.

Any investor that hasn’t learned about what happens to markets when they go curvilinear will soon find out.

Ding, ding, ding, ding.

How to Generate Stock Ideas

24 Nov 2013 08:55 pm | Vishal Khandelwal

In an interview with Warren Buffett in 1993, Adam Smith, author of Supermoney, asked how the small investor can find good investment ideas.

In an interview with Warren Buffett in 1993, Adam Smith, author of Supermoney, asked how the small investor can find good investment ideas.

Warren Buffett: I’d tell him to do exactly what I did 40-odd years ago, which is to learn about every company in the United States that has publicly traded securities, and that bank of knowledge will do him or her terrific good over time.

Adam Smith: But there are 27,000 public companies.

Warren Buffett: Well, start with the A’s.

Everybody knows that Warren Buffett gets his investment ideas largely from annual reports.

Of course, now he has become so influential that companies call him to share their own ideas. But, fifty years ago, Buffett was not the go-to guy if you wanted to sell your company or raise capital for your failing bank.

He was a small investor who was clawing his way up the investing street by reading whatever annual report came his way, and then finding his investment ideas that worked wonders in the subsequent years.

You are probably at the same stage Buffett was fifty years ago. But there’s a big advantage you have over the early day Buffett.

That advantage is – technology.

With annual reports now available at the press of a few buttons (on company websites and BSE), you can look through hundreds of companies in lesser time than it took Buffett to access ten companies.

You may ask, “But how do I select companies whose annual reports I should read?”

Well, one quick suggestion is what Buffett told Adam Smith – “…start with the A’s.”

I would simplify this for you…

- Take, for instance, the BSE-200 list of companies

- Remove all companies that you “know” are outside your circle of competence (Don’t worry if you remove lot of companies…because the size of the circle is not important, knowing its boundary is)

- For companies that remain, start reading annual reports of companies whose names start with A, then B, and so on.

If you find this difficult to implement (and it is), here are a few other ways you can create a list of companies you would like to do a deeper research on to generate stock ideas…

Remember, good ideas rarely come from…

- TV, newspaper analysis and breaking news

- Brokers and research analysts

- Friends, colleagues, and people you meet at social gatherings

…so you may rather do your own homework than relying on free tips, however enticing they may sound.

Screening Your Way to Stock-dom!

While I am not anymore a big fan of using readymade screeners to generate stock ideas – because you tend to substitute thinking with a lot of data – simple screeners still help me in doing the initial groundwork.

Also, while there are a few paid (and expensive) screeners available in the market – like Ace Equity, Prowess, Capital Line – I find a few free screeners to be very effective when it comes to the value I can derive from using them.

Here are three steps you can use while using three free screeners I use to do a basic analysis on companies…

Step 1: Use a Google Screener

Visit this Google Finance Stock Screener page and select “India” from the drop down list of countries, and then BSE or NSE from the stock exchange list.

Remove all entries like “Market Cap”, “P/E Ratio” etc, so that you can set your own criteria for screening. Then, screen for companies using these key numbers (you may add more screening criteria from those available)…

- 5-year sales growth – Between 10% to 50% – Neither too low nor too high to avoid extremes or cases with sharp rise and sharp falls that may revert to the mean

- 5-year EPS growth – Between 10% and 50% – Neither too low nor too high to avoid extremes or cases with sharp rise and sharp falls that may revert to the mean

- Latest Net Profit Margin – Between 5% and 75%

- 5-year Avg. Return on Equity – Between 15% and 100%

- Latest Debt/Equity Ratio – Less than 1x

- Latest Market Capitalization – At least Rs 2.5 billion (Rs 250 crore) to exclude extremely small companies

- Latest P/E ratio – Between 5x and 25x

- Volume – At least 100 shares traded daily

Here is how the screening and its output look like…

Note: Another good screener that a tribesmen has directed me to is from Financial Times – FT Equity Screener. It has greater number of criteria than Google’s screener, but does not display the results in INR. You must however try it out for sure.

Step 2: From the list of companies you get, exclude those outside your circle of competence – businesses you “know” you don’t understand (like I would exclude commodity businesses like metals and mining, or oil & gas businesses).

Step 3: Glance at the last 5/10 years’ financial performance on sites likeScreener or Morningstar. Look for trends in:

- Sales growth – Check for rising and stable growth

- Net margin – Stable / rising margin. Be wary of margins that are falling

- Return on equity – Stable or rising. Be wary of falling ROE

- D/E – Nil or small debt is fine. Be wary of companies where D/E > 1x

- FCF change – Morningstar gives the free cash flow calculation, which instantly tells you if the company is generating cash or burning it. Look for businesses that have generated positive FCF over the past few years

- Apart from the ratios given, calculate ones like FCF yield – FCF per Sharedivided by Stock Price, which tells you if the stock is cheap or expensive. An FCF yield of 5% or more is a good number to look at.

The best part about these two screeners – Screener and Morningstar – is that you can download companies’s financial performance in excel and then do you own analyses.

Better Alternative to Step 3

While you may use Screener or Morningstar to study the past 5/10 years’s performance of companies that you get from Step 1 and Step 2 above, a far better way is to pick up the annual reports of the resultant companies and then read them one by one.

After having used ready-made screens for the past few years, I have realized that you should not use numbers prepared by others, but rather generate them yourself. This way you get into the habit of actually reading annual reports and also get to learn what numbers you need to focus on.

Here are two videos that will tell you what you must focus on in an annual report…

If you can’t see the videos above, see here – Video 1 | Video 2

Ultimately, as you would realize, just a few numbers / facts / variables will help you understand what drives a given business.

I have seen analysts and investors trying to get perfect in their analysis by accumulating as many data points as possible.

But then, my experience suggests that trying to increase your confidence by gathering information that is supposedly unknown to most others really only makes you more comfortable with your investment decisions, not better at them, and is generally an unproductive use of your limited time.

Thus, I would suggest that after you arrive at your list of companies using any or a combination of methods suggested above, use a “Less is More Checklist” while reading the annual reports of the companies in your list.

Use the “Less is More” Checklist

Rather than obsessing with the bewildering fusion of news and noise, concentrate on a few key elements in stock selection, i.e., what are the 5-10 most important things you should know about any business you are about to invest in?

Of course, if I knew the exact answer I would have retired long ago! ![]()

Even if I could know all the facts about an investment, I would not necessarily profit. This is not to say that fundamental analysis is not useful. It certainly is.

But information generally follows the well-known 80/20 rule: the first 80% of the available information is gathered in the first 20% of the time spent.

So if I were to list down eight questions that, I believe, would help me do an 80% analysis of a business, they would be…

- Is the business simple to understand and run? (Complex businesses often face complexities difficult for its managers to get over)

- Has the company grown its sales and EPS consistently over the past 5-10 years? (Consistency is more important than speed of growth)

- Will the company be around and profitably better in 10 years? (Suggests continuity in demand for the company’s products/services)

- How has the company performed on Buffett’s earnings retention test?(Suggests how a company has used retained earnings in the past – a very important question to answer)

- Does the company have a sustainable competitive moat? (Pricing power, gross margins, lead over competitors, entry barriers for new players)

- How good is the management given the hand it has been dealt? (Capital allocation, return on equity, corporate governance, performance against competition)

- Does the company require consistent capex and working capital expenditure to grow its business? (Companies that have to spend continuously on such areas are like running on treadmills, which is not a good situation to have)

- Does the company generate more cash than it consumes? (Cash generators have a higher probability of surviving and prospering during bad economic situations)

These questions would help you answer whether the business you are looking into is great, good or gruesome as Warren Buffett has defined each one of them to be.

Ultimately, successful investing is all about doing your own research carefully and buying good businesses.

If you know a company well and you’ve done your homework, you can take advantage of situations when Mr. Market offers them on a platter, which he occasionally does.