“First, never buy a bank at twice its book value, Number two, don’t trust any bank with a superior earnings record, Number three, you are buying a pig in a poke because the assets are inherenetly unanalysable… ” “Then there are the contra rules, ” He went on, “such as the inability to earn exponential rates of return except through recklesness or fruad.” Also,” said Tisch…”a really smart person says to himself at a certain point that your pricing is set by the stupidest person in the market,” It is the marginal lender who makes the marginal loan at a bargain-basement rate, and it is impossible to compete with that optimist.

James Grant “Banking with Tisch” (October 6, 1986)

And that brings us to the lunatic valuation of the FANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google), which was also on display again this week. To wit, 100X+ PE multiples are always and everywhere a deformed artifact of central bank driven Bubble Finance, not the emission of an honest capital market.

The fact is, the greatest technology-based businesses of modern times accomplished its dramatic growth spurt in just over 20 quarters between 2011 and 2015. That was after the i-Phone incepted and the i-Pad worked up a serious head of steam.

Now Apple is pancaking or worse, and it is hard to believe that gimmick products like Apple Watch or Oculus can fill the hole from the fast fading i-Pad and the stalling i-Phone. No harm done, of course, and its entirely possible the APPL will have another modest growth run.

But here’s the thing. Apple essentially proves you can’t capitalize anything at 100X except in extremely rare cases because of the terminal growth rate barrier. That is, after a few years of red hot growth almost every large company’s organic growth rate bends toward the single digit path of GDP.

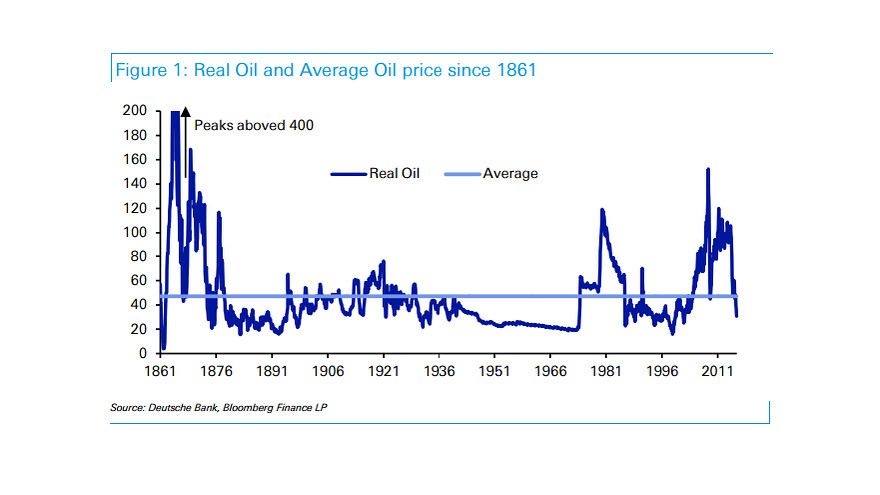

I’m wondering if people may take the wrong message from this chart. Here’s my read:

The high prices in the beginning were due to oil being a very desirable but very scare resource. Drilling only began in 1859 and the technology was primitive and inefficient.

Then entered J.D.Rockefeller, who brought major efficiencies to the industry and increased refining capacity to the point where it was in excess of that needed for kerosene (used in lamps), and so the price plummeted. There was another brief spike in price as Rockefeller gained what amounted to monopoly control of the industry in the late 1870s, and new applications for oil were found.

Thereafter, the price plunged due to improved efficiency and competition from other areas and abroad. Oil traded in a fairly broad but well-defined range for the next 60 years, depending on prevailing business conditions. The wide swings in prices during this period suggest that there is a positive feedback mechanism involved in the prices. Low prices make energy less expensive, which promotes increased economic activity, which increases demand, which causes higher prices, which quenches economic activity, which reduces demand, which reduces prices…

After WWII, with the discovery of the huge Arabian oil fields (as well as others) and the emergence of the US as the guarantor of stable world prices, there emerged a period of remarkable price stability from roughly the end of WWII onwards. Stability resulted from increases in demand being met with increases in supply at current prices, coupled with the price stability resulting from the Bretton Woods monetary system.

The next significant break came with the “Arab Oil Embargo(s)” of the 1970s. While there was an obvious political context here, the other part of the equation was that US production was peaking. There was a short respite once political conditions improved, but the underlying dynamic was that some of the important producers, the US in particular, were unable to keep up with local demand.

This situation became global in the early years of the 21st century, as demand in emerging economies ramped-up, while at the same time production from important established fields was in decline. New fields were found, but were typically much more expensive to exploit than the earlier fields. Since that time, the supply/demand dynamic has been at play, with price increases driven by increased cost and limited supply, and price declines being driven by poor economic conditions caused by the heretofore high prices. The feedback cycle outlined above is in full play, this time with prices being in a generally upward trend due to generally scarce supply at lower price levels.

My reason for pointing this out is that I’m not sure that identifying $47 as an average price is very meaningful. The bottom line is that demand for oil will be robust whenever prices allow for it, while supply at any given level will become scarcer as the “low-hanging fruit” is picked clean. My contention is that major price volatility with a generally upward trend is what we have to look forward to. This will continue until something happens to fundamentally change either the positive feedback mechanism or the fundamental long-term supply/demand relationship. So the $47 average price may be of historical interest, but may be of limited applicability going forward. (from an anonymous commentor).

—