FREE CLASS in New York City

Whitney Tilson through www.kaselearning.com will be teaching value investing and hedge fund entrepreneurship to the next generation of investors. His programs are aimed at experienced investors and are very hands-on, so they aren’t cheap ($1,500-$2,000/day), but for beginners, he is offering a free two-hour seminar, An Introduction to Value Investing, in midtown NYC (57th and 7th) on Wed., April 4th from 5:30-7:30pm, followed by a cocktail hour. If you’d like to come, just email wtilson@kaselearning.com and Whitney will send you details.

Investing and Hedge Fund/Entrepreneurship “Boot Camp” And other Courses.

I attended Whitney Tilson’s and Glenn Tongue’s February 6th – 8th Boot Camp. I was initially skeptical but pleasantly surprised.

Overall, I was impressed with the learning materials, the organization, and most importantly, the participants who attended. Whitney and Glenn were brutally honest and forthright in showing the rise and fall of their business. One can know the lessons of Munger, Buffett, Graham, and behavioral finance but still fall into a pit. Our main enemy is likely to be ourselves. There were many lessons taught, but my promise of confidentiality prevents me from giving details. The course would not be appropriate for a rank beginner, but for an entrepreneur who wishes to launch their own fund.

The main value–besides the lessons taught–would be to cultivate relationships with the participants including Whitney and Glenn. I wouldn’t go to Whitney to help you get a job, but if you do a rigorous analysis of a company, I am sure Whitney or Glenn could give you honest feedback. And if they liked your work, they might suggest how you could reach a larger audience. Also, your classmates could help. The opportunity to build strong relationships with knowledgeable investors and hedge fund managers would be invaluable for someone beginning their fund.

Each day was ten hours long with meals and cocktails afterwards, so you had plenty of opportunity to develop relationships.

60% of the course was how to improve as an investor, 20% life lessons, and 20% how to build your hedge fund.

See details here:

There are other courses available as well.

Make sure you receive at least a 10% discount on the course or other courses by using “CSI10“ when you register.

If you want details on my experience of the course and what you might expect, please don’t hesitate to email me at aldridge56@aol.com with BOOT CAMP in the subject line. I will be happy to discuss with you.

“Regarding last week, I was super impressed by the material. I liked the practical nature of the lessons they taught – a lot of courses exist that cover investing philosophy, but this was unique in its applicability to a start-up manager like myself.”

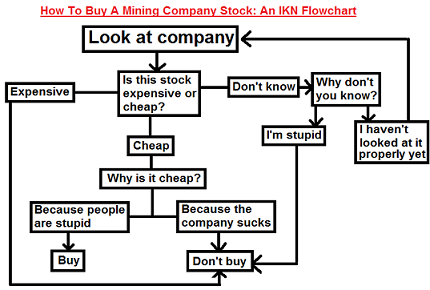

“The main lesson I learned from the course was to keep it simple. Look for the easy investments.”

“I actually really liked the emphasis on short selling, because it tends to be one of the great struggles of hedge funds that need to be long & short to justify the carry but have difficulty executing on compelling short ideas in the midst of a bull market.”

“I would have liked more on portfolio construction because that is what I am struggling with. Ditto for risk management and small funds. Things I loved – the interaction of our group, the LL case, the mea culpas of what Whitney and Glenn did right and wrong.”

All the participants told me that they both enjoyed the boot camp and found it useful in developing their fund.

Whitney solicited feedback each day, therefore, Whitney and Glenn should improve their course offerings.

I give a thumbs-up. To learn more about the boot camp/Kase Learning programs you can go to www.kaselearning.com.

Update:

I will periodically update information on Kase Capital for interested readers. If you learn anything from reading this post it should be to KNOW THYSELF! The market is an expensive place to find out. John Chew

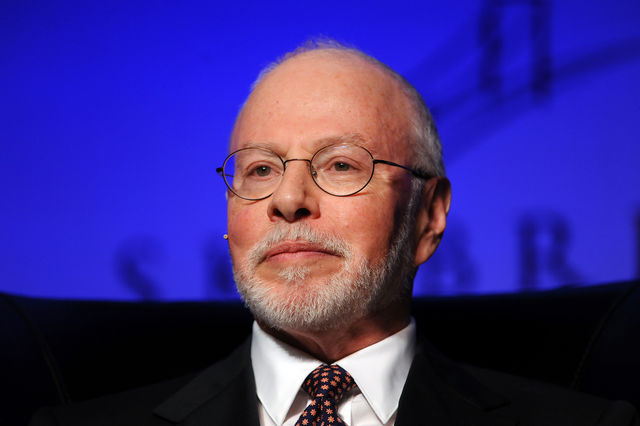

The hedge fund founder explains why his fund was “sucking the joy” out of his life — and why he’s turning its failure into a teachable moment.

By Michelle Celarier

March 20, 2018

Whitney Tilson’s Facebook friends surely thought he was on top of the world last summer.Photo after photo posted on the social media site tells the story of a rich, exciting life: There’s Tilson watching whales off the coast of Iceland. Next, he’s on the canals of Amsterdam with his wife and daughter. Just a few days later, he’s checking out Lenin’s tomb in Moscow. Last August he even climbed to the top of the famed Eiger mountain in the Swiss Bernese Alps, photographing every step of the arduous journey.

But to hear Tilson talk today, the reality was grim. After 18 years in the hedge fund business, his firm — Kase Capital Management — was losing money, and Tilson found himself dipping into hissavings to keep it afloat.

“I had lost my passion for the game,” Tilson confided in a two-hour, soul-searching interview about the events that led him to shut down his hedge fund last September. After gaining 184 percent, net — when the broader market was up only 3 percent — during the first 11 and a half years of his hedge fund’s existence, Tilson’s returns had been floundering. Since 2010, Tilson says, he trailed the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index, and in 2017 he had lost almost 9 percent on the year by the time he shut down his fund. “In an ironic twist, I always built my firm to survive the worst storm, but it was a nine year bull market — complacency and sunshine — that took me out.”

Tilson is one of several veteran hedge fund managers, including Eton Park Capital Management’s Eric Mindich, Hutchin Hill Capital’s Neil Chriss, Eclectica Asset Management’s Hugh Hendry, and Blue Ridge Capital’s John Griffin, who called it quits in 2017. Small hedge funds come and go with great regularity, but the inability of the industry’s stars to profit as the stock market soared to new heights has raised questions about the viability of the model. Tilson was a much smaller player than the others — at his peak he managed only $200 million — but his experiences are a window into the headwinds that have faced these former masters of the universe.

What distinguishes Tilson from many of his peers is his willingness to talk about the long, excruciating road down. “It’s hard, after seven years at sucking at something, to wake up and tap-dance to work. So, I found myself getting distracted. I wasn’t physically getting out of shape; it was the opposite. I was going and climbing mountains. This one part of my life, I was miserable at; I was having no success. It’s hard to have the self-discipline to focus all your attention like a laser, and all your spare time on a particular part of your life in which you’re getting so much negative reinforcement.”

Last year, as his fund’s losses began to mount, Tilson says, “I didn’t feel like I could look my investors in the eye and say, “˜Look, I’m losing you money, but I’m not doing anything else, 18 hours a day that I’m awake, the only thing I am doing is trying to turn performance around.’ ” The vacation photos notwithstanding, Tilson says he even felt guilty attending his daughter’s soccer games. “My hedge fund was sucking all the joy out of my life.”

Tilson’s introspection is uncommon for those in the hedge fund business, where selfconfidence and salesmanship are as important to success as any investing prowess. As Tilson readily admits, managers cannot afford to be frank while they are going through turmoil, lest they further hurt their business — and their investors. “The last thing you want to do is air your dirty laundry. That will further shake the confidence of your investors.”

But there’s another reason for Tilson’s uncommon openness: His experiences, both positive and negative, have led him to create a whole new business, turning Kase Capital into Kase Learning (Kase stands for the first letters of the names of Tilson’s wife and three daughters). From a small conference room at the New York Athletic Club, Tilson has started teaching the perils and profits of investing in general — and running a hedge fund specifically — to aspiring youngsters who don’t come out of big seeding platforms like Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management or a multibillion-dollar hedge fund.

“Unless you are the lucky 1 percent who has the chance of learning in an apprenticeship, how are you supposed to learn how to do this?” Tilson says. “Nobody teaches the next generation. There is not one business school on the planet that teaches anything really usable to starting up your own hedge fund.

“It’s so rare to talk to a manager who is injected with truth serum, isn’t it?” he asks as he details his long bumpy journey through hedge fund land. “But I don’t give a crap anymore.”