A new blog: www.valueuncovered.com I hope readers learn from this blog. My initial glance shows that this blog focuses on smaller companies. I an impressed with this student’s (aren’t we all students) thoughtful analysis. Don’t forget to always ask of the business has a franchise or not. Does the business generate above average returns on capital. Don’t be deceived by multiples of EV to EBITDA or EBIT. And always do your own independent analysis.

My favorite blog: www.greenbackd.com for those who invest in asset type investments; net/nets, special situations, and activist stocks.

Austrian Capital Theory

I highly recommend this article for understanding our current situation: http://www.thefreemanonline.org/features/austrian-capital-theory-why-it-matters/ See www.cafehayek.com.

http://www.thefreemanonline.org/features/austrian-capital-theory-why-it-matters/

Austrian Capital Theory: Why It Matters

by Peter Lewin • June 2012 • Vol. 62/Issue 5

With the resurgence of Keynesian economic policy as a response to the current crisis, echoes of past debates are being heard—in particular the debate from the 1930s between John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek. Keynes talked about the “capital stock” of the economy. He argued that by stimulating spending on outputs (consumption goods and services), one can increase productive investment to meet that spending, thus adding to the capital stock and increasing employment.

Hayek accused Keynes of insufficient attention to the nature of capital in production. (By “capital” I mean the physical production structure of the economy, including machinery, buildings, raw materials, and human capital—skills). Hayek pointed out that capital investment does not simply add to production in a general way but rather is embodied in concrete capital items. That is, the productive capital of the economy is not simply an amorphous “stock” of generalized production power; it is an intricate structure of specific interrelated complementary components. Stimulating spending and investment, then, amounts to stimulating specific sections and components of this intricate structure.

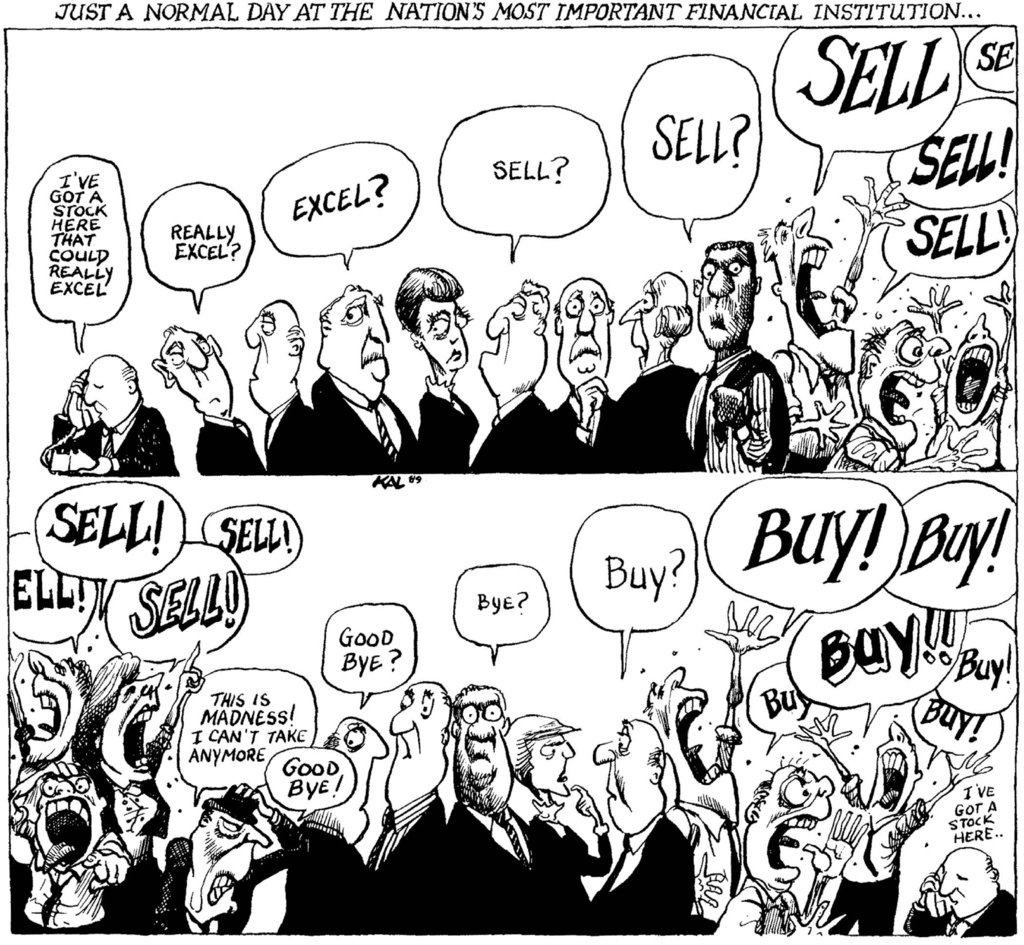

The “shape” of production is changed by stimulatory activist spending. And given that in a world of scarcity productive resources are not free, this change comes at the expense of productive effort elsewhere. The pattern of production thus gets out of sync with the pattern of consumption, and eventually this must lead to a collapse. Productive sectors, like dot-com startups or residential housing, become “overbought” (while other sectors develop less), and eventually a “correction” must occur. Add this distortion to the fact that the original stimulus must somehow eventually be paid for, and we have a predictable bust.

These Hayekian criticisms are once again relevant. It is necessary therefore to return to the nature of capital to clarify the issues. Hayek was working from foundations that were developed by his intellectual forebears in the Austrian school of economics. Specifically, it is the Austrian theory of capital that is relevant, and we should begin with that.

The Austrian Theory

The best known Austrian capital theorist was Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, though his teacher Carl Menger is the one who got the ball rolling, providing the central idea that Böhm-Bawerk elaborated. Böhm-Bawerk produced three volumes dedicated to the study of capital and interest, making the Austrian theory of capital his best-known theoretical contribution. He provided a detailed account of the fundamentals of capitalistic production. Later contributors include Hayek, Ludwig Lachmann, and Israel Kirzner. They added to and enriched Böhm-Bawerk’s account in crucial ways. The legacy we now have is a rich tapestry that accords amazingly well with the nature of production in the digital information age. Some current contributors along these lines include Peter Klein, Nicolai Foss, Howard Baetjer, and me.

The Austrians emphasize that production takes time: The more indirect it is, the more “time” it takes. Production today is much more “roundabout” (Böhm-Bawerk’s term) than older, more rudimentary production processes. Rather than picking fruit in our backyard and eating it, most of us today get it from fruit farms that use complex picking, sorting, and packing machinery to process carefully engineered fruits. Consider the amount of “time” (for example in “people-hours”) involved in setting up and assembling all the pieces of this complex production process from scratch—from before the manufacture of the machines and so on. This gives us some idea of what is meant by production methods that are “roundabout.”

(The scare quotes around time are used because in fact there is no perfectly rigorous way to define the length of a production process in purely physical terms. But, intuitively, what is being asserted is that doing things in a more complicated, specialized way is more difficult; loosely speaking it takes more “time” because it is more “roundabout,” more indirect.)

More Roundabout Production

Through countless self-interested individual production decisions, we have adopted more roundabout methods of production because they are more productive—they add more value—than less roundabout methods. Were this not the case, they would not be deemed worth the sacrifice and effort of the “time” involved—and would be abandoned in favor of more direct production methods. What are at work here are the benefits of specialization—the division of labor to which Adam Smith referred. Modern economies comprise complex, specialized processes in which the many steps necessary to produce any product are connected in a sequentially specific network—some things have to be done before others. There is a time structure to the capital structure.

This intricate time structure is partially organized, partially spontaneous (organic). Every production process is the result of some multi-period plan. Entrepreneurs envision the possibility of providing (new, improved, cheaper) products to consumers whose expenditure on them will be more than sufficient to cover the cost of producing them. In pursuit of this vision the entrepreneur plans to assemble the necessary capital items in a synergistic combination. These capital combinations are structurally composed modules that are the ingredients of the industry-wide or economy-wide capital structure. The latter is the result then of the dynamic interaction of multiple entrepreneurial plans in the marketplace; it is what constitutes the market process. Some plans will prove more successful than others, some will have to be modified to some degree, some will fail. What emerges is a structure that is not planned by anyone in its totality but is the result of many individual actions in the pursuit of profit. It is an unplanned structure that has a logic, a coherence, to it. It was not designed, and could not have been designed, by any human mind or committee of minds. Thinking that it is possible to design such a structure or even to micromanage it with macroeconomic policy is a fatal conceit.

The division of labor reflected by the capital structure is based on a division of knowledge. Within and across firms specialized tasks are accomplished by those who know best how to accomplish them. Such localized, often unconscious, knowledge could not be communicated to or collected by centralized decision-makers. The market process is responsible not only for discovering who should do what and how, but also how to organize it so that those best able to make decisions are motivated to do so. In other words, incentives and knowledge considerations tend to get balanced spontaneously in a way that could not be planned on a grand scale. The boundaries of firms expand and contract, and new forms of organization evolve. This too is part of the capital structure broadly understood.

Division of Knowledge

In addition, the heterogeneous capital goods that make up the cellular capital combinations also reflect the division of knowledge. Capital goods (like specialized machines) are employed because they “know” how to do certain important things; they embody the knowledge of their designers about how to perform the tasks for which they were designed. The entire production structure is thus based on an incredibly intricate extended division of knowledge, such knowledge being spread across its multiple physical and human capital components. Modern production management is more than ever knowledge management, whether involving human beings or machines—the key difference being that the latter can be owned and require no incentives to motivate their production, while the former depend on “relationships” but possess initiative and judgment in a way that machines do not.

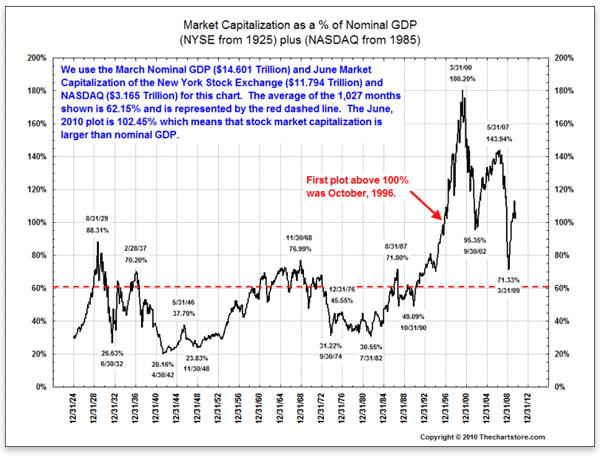

The foregoing provides the barest account of the rich legacy of Austrian capital theory, but it should be sufficient to communicate the essential differences between the Austrian view of the economy and that of other schools of thought. For Austrians the whole macroeconomic approach is problematic, involving, as it does, the use of gross aggregrates as targets for policy manipulation—aggregates like the economy’s “capital stock.” For Austrians there is no “capital stock.” Any attempt to aggregate the multitude of diverse capital items involved in production into a single number is bound to result in a meaningless outcome: a number devoid of significance. Similarly the total of investment spending does not reflect in any accurate way the addition to value that can be produced by this “capital stock.” The values of capital goods and of capital combinations, or of the businesses in which they are employed, are determined only as the market process unfolds over time. They are based on the expectations of the entrepreneurs who hire them, and these expectations are diverse and often inconsistent. Not all of them will prove correct—indeed most will be, at least to some degree, proven false. Basing macroeconomic policy on an aggregate of values for assembled capital items as recorded or estimated at one point in time would seem to be a fool’s errand. What do the policymakers know that the entrepreneurs involved in the micro aspects of production do not?

Capital and Employment

The folly is compounded by connecting capital and investment aggregates to total employment under the assumption that stimulating the former will stimulate the latter. Such an assumption ignores the heterogeneity and structural nature of both capital and labor (human capital). Simply boosting expenditure on any kind of production will not guarantee the employment of people without jobs. How else to explain that our current economy is characterized by both sizeable unemployment numbers and job vacancies? Their coexistence is a result of a structural mismatch: The structure (that is, the pattern of skills) of the unemployed does not match those required to be able to work with the specific capital items that are currently unemployed.

In fact the current enduring recession is basically structural in nature. It is the bust of a credit-induced boom-bust cycle, augmented by far-reaching production-distorting regulation. The Austrian theory of the business cycle was developed first by Ludwig von Mises, combining insights from the Austrian theory of capital with the nature of modern central-bank-led monetary policy. The theory was later used, with some differences, by Hayek in his debates with Keynes. Over the years its popularity and acceptance have waxed and waned, but it appears to be highly relevant to our current situation.

Dot-Com and Other Bubbles

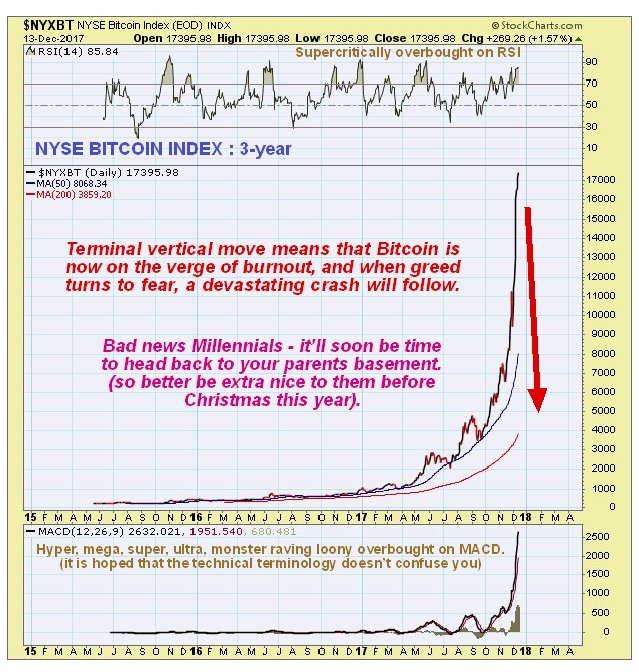

The dot-com boom no doubt reflected the advent of a pervasive new technological environment: the arrival and expansion of the digital age. It was a time of great promise and uncertainty and of enhanced risk-taking. Astronomical book values reflected expectations that in total could not be realized. A shakeup was inevitable—and known to be so. It was part of the market process. As the boom expanded, interest rates started to rise, reflecting the increased demand for a limited supply of loanable funds. This, as Hayek would have put it, is the natural brake of the economy, the signal and the incentive to slow down. But the Federal Reserve, not wishing to spoil the party, expanded reserves to keep interest rates low, thus allowing the boom to progress beyond its “natural” life. When the bust came it was bigger than it would have been had the cycle been allowed to run its natural course.

Notice how this story accords with our understanding of the capital structure. The expanding boom reflected entrepreneurs’ expectations of profitably making new capital combinations, only some of which would, in the event, prove to be profitable. But there was no way to know which they were ahead of time. That is why we need markets. Rising interest rates and the passage of time would tend to reveal the less viable ventures and weed them out. Keeping interest rates artificially low prevented this from happening, more so for those projects that were more interest-sensitive—namely, those that had a longer time horizon—or, loosely speaking in terms of our earlier discussion, contained more “time.”

But the dot-com collapse did not really mark the end of the cycle. Much of the extra liquidity was then directed into real estate, specifically into residential housing and into financial assets based on it. This investment channel was wide open as a result of a decades-long, recently intensified congressional and regulatory policy to expand homeownership in America. This is a familiar story that need not be repeated here. The result was an unprecedented expansion of home building and home purchases riding the tsunami wave of home prices. Once again the production structure was pushed out of sync with any kind of sustainable pattern of consumption.

The solution, from this perspective, is to remove the distortions—to allow the market process to “restructure” production. This would mean a sustained period of consolidation in the housing market, not a policy that attempts to revive it (to revive the bubble?) of the kind we are currently witnessing. But then today’s policymakers do not have the benefit of knowing Austrian capital theory.

Article printed from The Freeman | Ideas On Liberty: http://www.thefreemanonline.org

URL to article: http://www.thefreemanonline.org/features/austrian-capital-theory-why-it-matters/