If women ran the world we wouldn’t have wars, just intense negotiations every 28 days.–Robin Williams

The Value Vault is being worked on…..patience.

VALUE LINKS

To sign up for interesting value investing articles and links that are emailed to you every weekend don’t forget to ask to be placed on Steve Friedman’s (Santangel’s Review) email list. Contact: sfriedman@gmail.com

Greenblatt Discusses the Magic Formula and the Psychology of Investing.

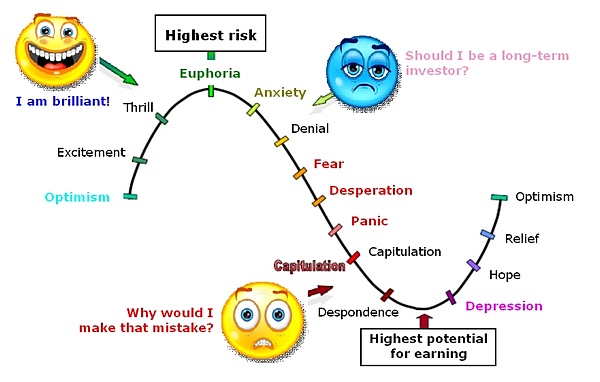

I included comments on this article because of what you can learn about investor psychology.

Adding Your Two Cents May Cost a Lot Over the Long Term

By Joel Greenblatt, Managing Principal and Co-Chief Investment Officer, Gotham Asset Management | Posted: 01-16-12

Wow. I recently finished examining the first two years of returns for our Formula Investing U.S. separately managed accounts. The results are stunning. But probably not for the reasons you’re thinking. Let me explain.

Formula Investing provides two choices for retail clients to invest in U.S. stocks, either through what we call a “self-managed” account or through a “professionally managed” account. A self-managed account allows clients to make a number of their own choices about which top ranked stocks to buy or sell and when to make these trades. Professionally managed accounts follow a systematic process that buys and sells top ranked stocks with trades scheduled at predetermined intervals. During the two-year period under study[1], both account types chose from the same list of top ranked stocks based on the formulas described in The Little Book that Beats the Market. But before I get to the results, let me rewind a little and review how we got here in the first place.

In 2005, I finished writing the first edition of The Little Book that Beats the Market and I panicked. The book contained a simple formula to pick stocks that encapsulated the most important principles that I use when making my own stock selections. The problem was that after I finished, I realized that the individual investors I was trying to help might try to follow the book’s advice but use poor quality company information found over the internet or a miscalculation of the formula to make unsuccessful stock investments (or possibly worse, they might use the book to learn how to write run-on sentences). I quickly put together a free website called magicformulainvesting.com that used a high quality database and that performed the calculations as I had intended. Unfortunately, it still wasn’t that easy to keep track of all the stocks, trades and timing that are necessary to follow the plan outlined in the book. In fact, my kids and I ended up having a tough time keeping track, too.

So after hundreds of emails from readers asking for more help in managing their portfolios, I had an idea. It was based on an idea I had long ago about creating a “benevolent” brokerage firm that sought to protect its customers from the most common investing errors. The firm would still let clients pick individual stocks, but those stocks would have to be selected from a pre-approved list based on the principles and formula outlined in the book. We would encourage clients to hold a portfolio of at least 20 stocks from this list to aid in the creation of a diversified portfolio and to send them reminders to make trades at the proper time to help maximize tax efficiency. We wouldn’t allow margin accounts so that customers could pursue this investment strategy over the long-term.

At the last-minute after creating the site, Blake Darcy, the CEO of the new venture and the founder of pioneering discount broker DLJdirect (in other words, he knows a thing or two about individual investors) suggested we make one simple addition. He said, why don’t we give customers a check box which essentially says “just do it for me”? In other words, this “professionally managed” account would follow a pre-planned system to buy top ranked stocks from the list at periodic intervals. No judgment involved, just automatically follow the plan.

So, what happened? Well, as it turns out, the self-managed accounts, where clients could choose their own stocks from the pre-approved list and then follow (or not) our guidelines for trading the stocks at fixed intervals didn’t do too badly. A compilation of all self-managed accounts for the two-year period showed a cumulative return of 59.4% after all expenses. Pretty darn good, right? Unfortunately, the S&P 500 during the same period was actually up 62.7%.

“Hmmm….that’s interesting”, you say (or I’ll say it for you, it works either way), “so how did the ‘professionally managed’ accounts do during the same period?” Well, a compilation of all the “professionally managed” accounts earned 84.1% after all expenses over the same two years, beating the “self-managed” by almost 25% (and the S&P by well over 20%). For just a two-year period, that’s a huge difference! It’s especially huge since both “self-managed” and “professionally managed” chose investments from the same list of stocks and supposedly followed the same basic game plan.

Let’s put it another way: on average the people who “self-managed” their accounts took a winning system and used their judgment to unintentionally eliminate all the outperformance and then some!

How’d that happen? Well, here’s what appears to have happened:

(You might consider this a helpful list of things NOT to do!)

1. Self-managed investors avoided buying many of the biggest winners.

How? Well, the market prices certain businesses cheaply for reasons that are usually very well-known. Whether you read the newspaper or follow the news in some other way, you’ll usually know what’s “wrong” with most stocks that appear at the top of the magic formula list. That’s part of the reason they’re available cheap in the first place! Most likely, the near future for a company might not look quite as bright as the recent past or there’s a great deal of uncertainty about the company for one reason or another. Buying stocks that appear cheap relative to trailing measures of cash flow or other measures (even if they’re still “good” businesses that earn high returns on capital), usually means you’re buying companies that are out of favor. These types of companies are systematically avoided by both individuals and institutional investors. Most people and especially professional managers want to make money now. A company that may face short-term issues isn’t where most investors look for near term profits. Many self-managed investors just eliminate companies from the list that they just know from reading the newspaper face a near term problem or some uncertainty. But many of these companies turn out to be the biggest future winners.

2. Many self-managed investors changed their game plan after the strategy underperformed for a period of time.

Many self-managed investors got discouraged after the magic formula strategy underperformed the market for a period of time and simply sold stocks without replacing them, held more cash, and/or stopped updating the strategy on a periodic basis. It’s hard to stick with a strategy that’s not working for a little while. The best performing mutual fund for the decade of the 2000’s actually earned over 18% per year over a decade where the popular market averages were essentially flat. However, because of the capital movements of investors who bailed out during periods after the fund had underperformed for a while, the average investor (weighted by dollars invested) actually turned that 18% annual gain into an 11% LOSS per year during the same 10 year period.[2]

3. Many self-managed investors changed their game plan after the market and their self-managed portfolio declined (regardless of whether the self-managed strategy was outperforming or underperforming a declining market).

This is a similar story to #2 above. Investors don’t like to lose money. Beating the market by losing less than the market isn’t that comforting. Many self-managed investors sold stocks without replacing them, held more cash, and/or stopped updating the strategy on a periodic basis after the markets and their portfolio declined for a period of time. It didn’t matter whether the strategy was outperforming or underperforming over this same period. Investors in that best performing mutual fund of the decade that I mentioned above likely withdrew money after the fund declined regardless of whether it was outperforming a declining market during that same period.

4. Many self-managed investors bought more AFTER good periods of performance.

You get the idea. Most investors sell right AFTER bad performance and buy right AFTER good performance. This is a great way to lower long-term investment returns.

So, is there any good news from this analysis of “self-managed” vs. “professionally managed” accounts? (Other than, of course, learning what mistakes NOT to make—which is pretty darn important!) Well, I can share two observations that are, at the very least, fun to think about:

First, most clients ended up asking Formula Investing to “just do it for me” and selected “professionally managed” accounts with over 90% of clients choosing this option. Perhaps most individual investors actually know what’s best after all!

Second, the best performing “self-managed” account didn’t actually do anything. What I mean is that after the initial account was opened, the client bought stocks from the list and never touched them again for the entire two-year period. That strategy of doing NOTHING outperformed all other “self-managed” accounts. I don’t know if that’s good news, but I like the message it appears to send—simply, when it comes to long-term investing, doing “less” is often “more”. Well, good work if you can get it, anyway.

[1] The study reviewed the period May 1, 2009 to April 30, 2011. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

[2] Source: Morningstar study quoted in The Wall Street Journal, December 31, 2009, “Best Stock Fund of the Decade.”

Comments on the Article

These stories happen with so many good investment processes. The investor does not have enough faith to weather the inevitable, occasional loss, and begins to ‘fine-tune’ the system into failure.

One of my favorite mutual fund investments before I started picking my own stocks was (still is) Fidelity Contrafund. And it matches my personality. If the crowd is going one way, I tend to go the other. I am skeptical of the conventional wisdom since I learned most Europeans though Columbus would fall off the end of the Earth and painful lessons, like in the tech and real estate booms. When everyone’s getting into the act, it’s time to hit the exits. I brought that style into my own stock investing and tend to want to do the opposite of what most investors do.

Then there’s one of the best lessons I learned from Jim Cramer. It doesn’t matter where a stock or company has been. What matters is where it is going. Period. (OK, history and a track record count. But that didn’t help investments in companies like GRMN, RIMM… AAPL or WMT at critical points of their history).

Morningstar’s forward-looking, fair value, star, moat and certainty ratings give me something solid to anchor to. The bigger the discount to fair value, moat and higher certainty, the more I have invested. Then adjust my position as it changes significantly, taking profits on winners and buying more as a good company’s stock gets cheaper. A simple spreadsheet based on those principles helps keep my discipline and emotions in check.

I think most investors are a lot like I used to be. Lack of confidence in the businesses behind our investments, putting too much weight in what others, including Mr. Market think and being impatient. I’ve made all the mistakes outlined herein and I’m still no rock-solid, Warren Buffett type. But getting there with practice, study and experience. swsalf

Jan 16 2012, I’m a little surprised that Morningstar would publish such a blatant sales pitch on their website.

Let me see, what are we saying here? Let me manage your money for 1% and I will do better than you can. The returns posted on his website commence 2Q’09 – a convenient time to start keeping score – claim to have beaten the S&P 500 by a cumulative 10% or so to date. Not a word about risk incurred relative to the indices. The value approach he touts didn’t work so will in 2008 – witness some well-known value managers stocking up on Countrywide and other financials when they were so cheap.

The true measure of good management is how well you do in downturns, not whether you get an extra 1% during an up market.

I am a self-managed investor (more than two decades) and I do not see this as a sales pitch. The faults identified are real and need to be addressed if one is to become and remain a successful self-managed investor. If you are unwilling to examine your temperament and actions, then perhaps having your money professionally managed may be a better course to investing success. A key, but unstated point is one must take responsibility for their own decisions, whether it be self-managed or professionally managed. A failure to accept that responsibility will lead to misplaced criticism when things go south.

As to your second point, you have to start at some point in time. Granted, starting in May 2009 does slightly tilt the results, but does not negate the message. As a long-term value investor, I am now and was fully invested during the 2008-2009 downturns. And my portfolio was down more than 50% on paper. That did not prevent me from finding the necessary funds (I did not add money to the portfolio) to take advantage of fire-sale prices on many companies. With some repositioning, my paper loss was more than recovered in less than nine months and the portfolio has grown significantly since then. While I may not have made as much on those positions sold, they were all sold for a profit even at the depths of the downturn.

Although having one’s total portfolio down more than 50% can be unnerving, it is not unusual to see the share price of individual companies vary by 50% or more in a year’s time. This is really what the article is about – first, realizing when the market is miss-pricing a company and using that to your advantage to add to your position; second, to maintain positions over time, not concerning yourself with short-term losses or gains. That is what enabled me to sell positions at the depths of 2008-2009 while still enjoying double-digit Compound Annual Growth Rates (CAGR) on those positions.

The importance is having a well-defined plan which accounts for multiple scenarios, providing the flexibility to respond appropriately with a goal of enhancing one’s overall long-term returns. Without an appropriate plan, the investor, self-managed or professional, is subject to the whims of the market and will inevitably suffer lower returns than otherwise possible.

Thanks, Bob.

Many points of this article are well taken. But I have the same concern as yourself. The manager mentioned that “Many self-managed investors changed their game plan after the strategy underperformed for a period of time.” So why did he decide to write this article now, rather than at the time when his strategy “underperformed for a period of time”? wagnerjb

Joel: you describe the specific stocks as value stocks, yet you benchmark your performance against the S&P500? I suspect the professional performance might look more mediocre if you compared it to a more appropriate benchmark. swsalf

I’m a self-managed investor too and have been for quite a while. My five-year return as of 12/11 was 82% cumulative (Fidelity’s calculation) – that includes 2008.

I would certainly agree with the comments above on having a plan and following it. Granted, the article does speak to that. Indeed, it is probably the main point.

Having said that, returns in up and down markets do depend on what the plan is. Even more importantly when you are retired – as I am – and living on your portfolio. A 50% decline in portfolio value would be a disaster for most retirees, particularly if they are relying on capital gains for income. Withdrawals from a depressed portfolio for more than a year or so can put you in a situation from which you might never fully recover. That’s why there’s been so much in the literature about carrying very large cash cushions recently (which I don’t agree with either, incidentally).

I live on a portion of our portfolio’s income, so moderate swings in total value don’t affect us much. But I do favor equity investing with capital (or more importantly – income) preservation in mind. Most money managers do not. They are competing against an index and big decline is still success, if they’re up over the index. If you’re on a twenty year horizon, this will probably work for you. But if not, a black swan event like 2008 is not good and should be recognized as a probability.

Value does not always work. Wally Weitz presumably knows what he’s doing and his 5 year return is ca. -3% (Morningstar’s number) versus the S&P 500. In large part because of the bets he made that in the 2008 time frame that turned out to be value traps.

My biggest problem with this article is that any “magic formula” for investing needs to be tested through up and down markets. Touting total return over a very good past 2.5 years is at best incomplete-some would say misleading. Rick Ferri

I have two “professionally managed” accounts with formula investing. I believe in the strategy. My results are varying significantly in the small amount of time I’ve been invested. An account opened in April 2010 is losing to the S&P 500 index by 7.17%. Another account opened May 2010 is beating the S&P by 6% (both account results before the 1% annual fee).

My Question for Joel, is “what is the average return for all investors at Formula Investing?”, not just the accounts that started in May 2009. How much does timing changes the results? My personal experience (limited to two accounts, a terrifically small sample size) is over a 13% difference in almost two years. And, perhaps more significantly, average out to ~0% improvement on the S&P 500 index.

I have had a managed account with Formula Investing for 24 months and my current total return is 19.36%. That’s a far cry from 84%. He calls it a compilation of the funds but that is disingenuous to claim those returns. Mdlmdl;

I also have a formula investing account, where I first opened it and funded it about 25 months ago. So far, it has tracked the S&P 500 fairly closely. Magic Formula investing did much better than the S&P 500 from when it first started in about April 2009 thru about December 2009. Since then, it has done about the same (from about December 2009 thru December 2011) as the S&P 500. Joel gives the monthly performance versus the S&P 500 on the website.

I’m thinking that there is a good chance that it has done well in January 2012 given that some of the beaten down bargain stocks have done very well within the last few weeks.

I have a couple of beefs with Formula Investing. First, I hate to pay the 1% fee for what I could really do for myself for a lesser total cost (assuming that you have > $100,000 invested there, which I think now is the minimum allowed to start an account.) All you really need to pay is about 40 trades per year (buys plus sells combined on a running count of 20 stocks) at a discount broker, which would be about $240 per year, much less than > $1,000 per year paid to Joel and company.

My second beef is that Formula Investing sets a fairly high floor to the market cap of the companies that it buys shares for clients. I’d like it to offer the option of bringing down the market cap to, say, around $1.5 billion. Then, I think the formula would return slightly higher results over the long run, compared with big-cap only firms.

I have sent emails expressing this last view to the Formula Investing people. But, they don’t seem to forward my suggestions on up the line. David

www.formulainvesting.com/actualperformance_MFT.htm

You can see that Formula Investing beat the S&P 500 by about 16% from its inception in May 2009 thru the end of September 2009. Then, over the next eight quarters (24 months) it ended up essentially equaling the S&P 500’s performance.

—

My point/question is how much do the results vary based on starting date?

The “formula” selects a different set of stocks on any given day based on Joel’s criteria. My results vary considerably. The results Joel post are, I believe, from one discreet starting date. The results from my “April 2010 to now” account do not equal the S&P (under-perform by ~7%) at the end of the 22 month period.

Is variation expected? Absolutely. But what is the average return of all accounts/starting dates?