A Great Interview: The Forging of a Skeptic_Buffett

Snippets:

Learn about investigative journalism to become better at investing

Alice: Yes, I will give away some of my secrets. People would do well to study investigative journalism. Read something like Den of Thieves or A Civil Action and try to reverse engineer how it was reported.

Here are three other great books on conversing with people, understanding their real motives, and just generally understanding how the human mind works.

- The Craft of Interviewing by John Brady.

- The Zen of Listening by Rebecca Shafir.

- The Moral Animal by Robert Wright.

The Work of a Securities Analyst at a Wire House

You may wonder why analysts at banks hedge themselves so much – on the one hand this, on the other hand that. Partly it can be lack of courage. But someone is always trying to lawsuit-proof your opinion. Decisive statements are lawyered into “may, can, could, might, potentially, appears” instead of “is, does, should, will,” much less “look out below.”

The time pressures that work against quality research are also well-known. You write-up a lot of inconsequential things, especially what I call “elevator notes” (this quarter “X was up and Y was down”). Instead of writing original or probing views, you are really incentivized to spend as much time as possible marketing.

Also, if you adhere to consensus, it does protect your career. There’s an old saying that no one ever got fired for buying from IBM. Nobody ever got fired for making a wrong estimate that was within sell-side consensus.

Whereas, if you break from consensus, you really can’t afford to be wrong very often. That phenomenon really drives the sell-side. It can be overt, such as when we were judged on how “commercial” our work was. This is a veiled threat, because, of course, our work has to be marketable in order for us to have a job. The firms essentially want two things that are incompatible.

—

Focus on the Essentials

Miguel: It’s funny and I hope one day you can meet my boss. But you can tell him anything in the world (about an investment) but he always circles back to two questions

- Is it a good company, and

- Is it cheap?

Alice: Sure.

Miguel: I think that I am a little bit like you in that I love thinking about things. But I also find it very easy to get lost in details while forgetting to ask, “Is this something I even want to own in the first place?”

Alice: One trap is not probing deep enough to really answer whether a particular investment opportunity is a good business. It’s easy to make a facile judgment about that based on a summary description of a business. The sheer breadth of different business and investment opportunities in a modern capital market creates an overflow of information that leads many investors to have short attention spans in thinking about companies comparatively.

Curiosity is an inherent kind of arbitrage that no amount of computer technology can overcome. Warren makes it sound so simple to know what is and is not a truly good business – and great business do resonate very clearly when you understand why they are great and especially when they’ve been identified as successful investments by an investor like Warren Buffett and proven so with hindsight – but like many things in investing, Buffett makes it sound easier than it is. When it comes to appreciating something that is special about a business that others do not, I’ve learned that the devil really is in the details.

—

Miguel: How is Warren different from other value investors?

Alice: He’s more interested in money, for one thing (laughs).

In terms of how that affects his investing behavior, number one, in his classic investments he expends a lot of energy checking out details and ferreting out nuggets of information, way beyond the balance sheet. He would go back and look at the company’s history in-depth for decades. He used to pay people to attend shareholder meetings and ask questions for him. He checked out the personal lives of people who ran companies he invested in. He wanted to know about their financial status, their personal habits, what motivated them. He behaves like an investigative journalist. All this stuff about flipping through Moody’s Manual’s picking stocks … it was a screen for him, but he didn’t stop there.

Number two, his knowledge of business history, politics, and macroeconomics is both encyclopedic and detailed, which informs everything he does. If candy sales are up in a particular zip code in California, he knows what it means because he knows the demographics of that zip code and what’s going on in the California economy. When cotton prices fluctuate, he knows how that affects all sorts of businesses. And so on.

The third aspect is the way he looks at business models. The best way I can describe this is that it’s as if you and I see an animal, and he sees its DNA. He isn’t interested in whether the animal is furry; all he sees is whether it can run and how well it will reproduce, which are the two key elements that determine whether its species will thrive.

I remember when his daughter opened her knitting shop. Many parents would say, I’m so proud of Susie, she’s so creative, this is something of her own, maybe she can make a living at it. Warren’s version is, I’m so proud of Susie, I think a knitting shop can produce half a million a year in sales, they’re paying whatever a square foot for the storefront, and labor is cheap in Omaha.

It was similar when Peter was producing his multimedia show, The Seventh Fire. Many parents would say, wow, my son has pulled off a critically acclaimed show. Warren obviously thought that, but what he articulated was, they’re charging $40 a ticket, I think the Omaha market is too small for that price point, whereas in St. Louis they may cover the overhead, and I think he paid too much for the tent because the audience doesn’t really care what kind of tent it’s sitting in and it hurts margins, etc.

Read the entire interview:

http://seekingalpha.com/article/235292-behind-the-scenes-with-buffett-s-biographer-alice-schroeder

Investigative Journalism and Brookfield Asset Management

Repetitive Advantage: Broad Run Investment Management:Broad-Run-VII-Profile-Nov-2013

Buying Jan 2015 $15 call option at $3.00 in ABX

A special situation since there is a change in Board. If ABX can survive its balance sheet by improving its low cost assets, then there could be 100% to 200% upside with gold prices above $1,250. Right now we are in tax selling as well as a weak gold environment. ABX’s management says they will pare down/sell off their high cost mines. If gold goes sub- $1,000, then ABX could really struggle.

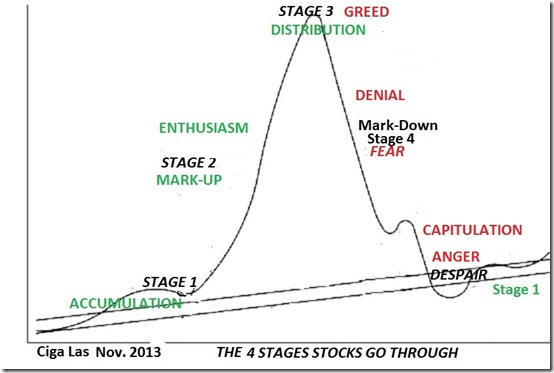

Look familiar?