A. Gary Shilling from Forbes Magazine

October 22, 2013

When the Fed started talking about reducing its $85 billion monthly purchases of Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities in May, Treasury bonds started to fall (chart 1) and yields jumped (chart 2).

Although Fed officials have vigorously denied that tapering signals an impending rise in interest rates, investors obviously didn’t believe the central bankers.

Many interest rate forecasters shout that the three-decade-long decline in Treasury bond yields is over, and they may be right-finally. These same pundits have been saying so repeatedly ever since rates started down in 1981.

As I discussed in my recent book, The Age of Deleveraging, and in many Insights before and since, back in 1981, few agreed with me that serious inflation was unwinding and interest rates would fall. Indeed, the consensus called for rates to remain high or even rise indefinitely.

Yet when 30-year Treasury yields peaked at 15.21% in October of that year, I stated that inflation was on the way out and “we’re entering the bond rally of a lifetime.” Later, I forecast a drop to a 3% yield. Again, most other forecasters thought I was crazy.

Most investors have a distinct anti-Treasury bond bias, and not just because they fervently believe that serious inflation and leaping yields are inevitable. Stockholders inherently hate them. They say they don’t understand Treasury bonds. But their quality has been unquestioned, at least until recently, and their prices rose promptly in 2011 after S&P downgraded them.

Treasurys and the forces that move yields are well-defined-Fed policy and inflation or deflation are among the few important factors.

Stock prices, by contrast, are much more difficult to fathom. They depend on the business cycle, conditions in that particular industry, Congressional legislation, the quality of company management, merger and acquisition possibilities, corporate accounting, company pricing power, new and old product potentials, and myriad other variables.

Stockholders do understand that Treasurys normally rally during weak economic conditions, which are negative for stock prices, so they consider declining Treasury yields to be a bad omen. Brokers also don’t want to recommend Treasurys since commissions on them are low, and investors can avoid commissions altogether by buying them directly from the Treasury.

Wall Street denizens also disdain Treasurys, as I learned firsthand while at Merrill Lynch and then White, Weld years ago. Investment bankers didn’t want me along on client visits when I was forecasting lower interest rates. They wanted projections of higher rates that would encourage corporate clients to issue bonds immediately, not wait for lower rates and cheaper financing costs. That’s what’s happening today in anticipation of Fed tightening and higher interest rates-more financing to pay for mergers and acquisitions as well as other needs.

Professional managers of bond funds are a sober bunch who perennially fret about inflation, higher yields, and subsequent losses of principal in their portfolio. But if yields fall, they don’t rejoice over bond appreciation but worry about reinvesting their interest coupons and maturing bonds at lower yields.

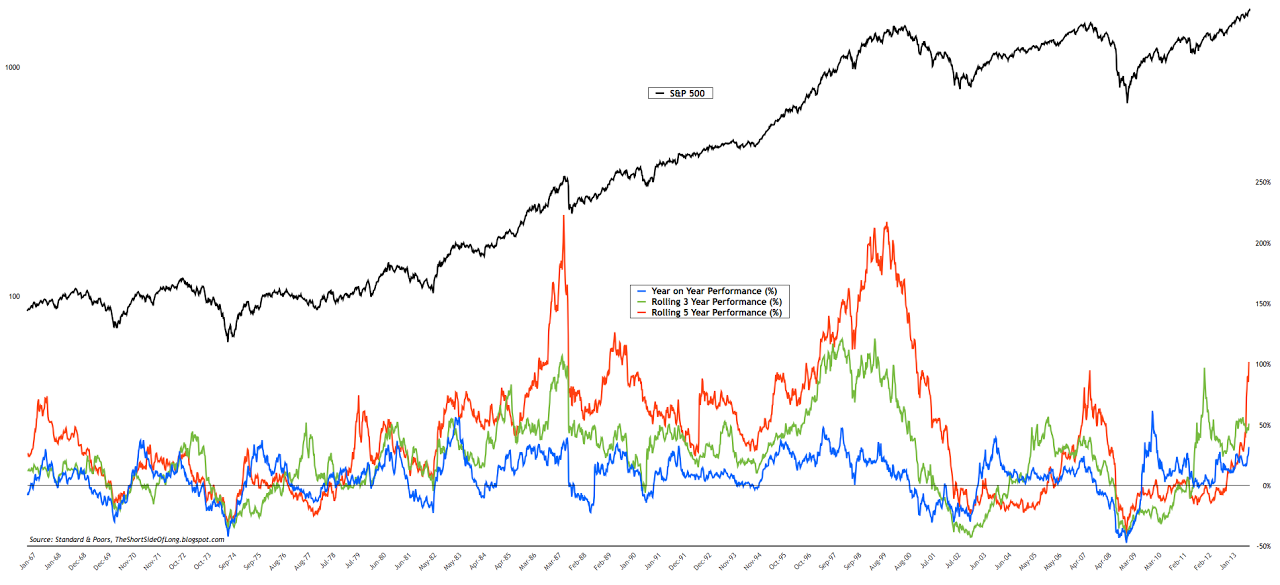

This disdain for bonds, especially Treasurys, persists despite their vastly superior performance vs. stocks since the early 1980s. Starting then, a 25-year zero-coupon Treasury, rolled into another 25-year annually to maintain the maturity, beat the S&P 500, on a total return basis, by 6.1 times (chart 3), even after the recent substantial bond sell-off.

This is one of our very favorite charts since we have actually participated in this marvelous Treasury bond rally as forecasters, portfolio managers and investors. And please note that we’ve never, never, never bought Treasurys for their yield. We couldn’t care less what the yield is-as long as it’s going down! We want Treasurys for the same reason that most of today’s stockholders want equities-appreciation.

It is true the Fed usually starts to raise the federal funds rate it controls before economic expansions are very old. This time, however, any move towards higher rates is likely to be some time off, not until the Age of Deleveraging and the related slow growth are over. Normally, deleveraging after major financial crises takes a decade to complete. Since deleveraging this time started in 2008, there’s about another five years to go.

Meanwhile, I believe Treasury yields are more likely to go down than up for a number of reasons. First, with slow economic growth persisting, gridlock in Washington, business uncertainty and ample supplies of capacity and labor on a global scale, the U.S. employment situation will likely remain weak.

The Fed has said it wouldn’t raise its federal funds rate until the unemployment rate broke 6.5%. Nevertheless, that target is fading because it’s decline in primarily the result of the falling labor participation rate, not rising employment. As investors more and more understand the Fed’s falling unemployment rate target, Treasury yields, which have anticipated a rise in rates, will probably decline as they have recently.

Inflation is close to zero and deflation is probably only being forestalled by the earlier massive fiscal and continuing monetary stimuli. But fiscal drag has replaced stimuli, resulting in the falling federal deficit. Also, the impending Fed tapering won’t tighten credit by reducing excess bank reserves through central bank sales of securities, but it will reduce the monthly additions to that $2.2 trillion horde.

For some time, I’ve believed that the Grand Disconnect between investors’ focus on Fed largess and their lack of interest in limping economic performance was unsustainable. Notice (chart 4) the close correlation between the rising S&P 500 index and the expanding balance sheet of the Fed since it started flooding the economy with money in August 2008.

I’ve e also been looking for a shock to close that Grand Disconnect. The negative effects of the federal government shutdown on consumer and business confidence and, even more so, the devastating fallout from a failure to raise the debt limit this month may serve that purpose. The recent decline in stock prices may be a prelude.

A substantial drop in stock prices will benefit Treasurys, not because of the economic weakness and likely deflation generated by the bear market-generating shock but also due to the resulting investor rush to Treasurys as the ultimate safe haven.

Furthermore, stocks are vulnerable. The S&P 500 index recently reached an all-time high but corrected for inflation, it remains in a secular bear market that started in 2000 (chart 5). This reflects the slow economic growth since then and the falling price-earnings ratio, and fits in with the long-term pattern of secular bull and bear markets.

Furthermore, from a long-term perspective, the P/E on the S&P 500 is 44% above its long run average of 16.5 (chart 6), and I’m a strong believers in reversion to well-established trends, this one going back to 1881. Also, since the P/E in the last two decades has been consistently above trend, it probably will be below 16.5 for a number of years to come.

Finally, stocks are vulnerable because of the elevated level of profit margins. As a share of national income, profits recently reached a record high as American business in recent years reacted to the lack of pricing power with falling inflation and to the meager sales volume growth by slashing labor and other costs as the route to bottom line growth.

But productivity growth engendered by cost-cutting and other means is no longer easy to come by. Also, neither capital nor labor gets the upper hand indefinitely in a democracy, and compensation’s share of national income has been compressed as profit’s share leaped.

In addition, corporate earnings are vulnerable to the likely strengthening of the dollar, which reduces the value of exports and foreign earnings by U.S. multinationals as foreign currency receipts are translated to greenbacks.

In our Jan. 2013 Insight, I predicted a further decline in the 30-year Treasury bond yield from 2.9% at that time to 2.0%. I also expected the 10-year Treasury note yield to drop from the then-1.73% level to 1.0%. Rates did fall until April, but then rose sharply until recently. The 30-year bond yield jumped to 3.92% before receding to the current 3.70% while the 10-year note yield reached 2.99% but is now 2.62%.

My earlier targets are probably too optimistic for this year but I do expect further declines in Treasury yields in future quarters. The “bond rally of a lifetime” will end some day, but it probably isn’t over yet.

Excerpted from October issue of Gary Shilling’s Insight. Gary Shilling is president of A. Gary Shilling & Co. and author of The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies For A Decade Of Slow Growth And Deflation (John Wiley & Sons, 2011). He is also the editor of Gary Shilling’s Insights newsletter. (source: www.shortsideoflong.blogspot.com)

Have a good weekend. I hope to be back posting as life returns to normal.