Abbott Laboratories (ABT)

We began with Novartis (NVS), a Swiss pharmaceutical company in this post: http://csinvesting.org/2011/11/29/what-the-market-is-paying-currently/#comments

Adib, a contributor, who runs: http://motiwalacapital.com/ posted a suggestion to add to the portfolio of compounding machines. Abbott Laboratories (ABT).

Adib writes, “I have a potential candidate for the rest of the portfolio…..A company with $5.7 in after-tax free cash-flow. Sales, cash flows, EPS and dividends and book value have grown about 9% over the past 10 years and are estimated to continue growing 7% over the next few years. Debt is 39% of total capital. Ret. On total capital has averaged 18% over the past ten years; return on equity has been 25% on average. Dividend yield is 3.6% and 40% of net profits.”

Go here for the Value-line: Abbott Labs (ABT)_VL and for the 25 year SRC Chart: ABT_25 Yr Chart and for the 50 year SRC Chart: ABT_50 Yr Chart (We like to think long-term). Note how the company outperforms in weak markets similarly to NVS.

ABT certainly fits the critieria of a stalwart franchise. The company has patent protection with economies of scale in research and development. 18 more compounding machines to fill out our minimum diversification of 20 companies.

Joe Rosenberg: The Best Opportunities in Half a Century.

Big Companies (Especially High Quality Franchises) Are Cheap!

Since we are on the subject, I thought you might enjoy reading this: The Best Opportunities in Half a Century, an interview by Joe Rosenberg, Investment Officer for Loews Corporation. You will note that Mr. Rosenberg mentions ABT as an investment. Is Mr. Rosenberg front-running Adib?

http://online.barrons.com/article/SB50001424052748703922804577066323160174632.html?mod=BOL_article_snippet_popview#

I am not a fan of Barron’s because I sometimes view the paper as a CNBC proxy where Wall Street sharpies sell their stock to the unwary. However, I do perk up when an experienced investor speaks.

That’s what veteran strategist Joe Rosenberg sees, and some of the best bargains, he says, are in the Dow Jones Industrials.

Joe Rosenberg is known for his candor, and for his understanding of all major asset classes. That comes from 50 years of experience on Wall Street, and his deep knowledge of markets and financial history. After beginning his career as an airline analyst at Bache in the 1960s, he was hired in 1973 by the late Larry Tisch at Loews, the New York conglomerate controlled by the Tisch family.

Rosenberg recalls that some people, including Barron’s columnist Alan Abelson, told him that he might not last long at Loews because he and Tisch both were too strong-willed to get along well.

Yet, Rosenberg has been there ever since. He was chief investment officer until 1995, when he became chief investment strategist. He’s also an advisor to Loews’ current CEO, Jim Tisch, Larry’s son. In addition, Rosenberg is a director of CNA Financial, the property-and-casualty insurer controlled by Loews.

“I feel like a kid in a candy store… I don’t know where to begin.…The best companies in the world are now some of the cheapest stocks.” — Joe Rosenberg

Barron’s has interviewed him on several occasions, most recently in February 2008. He then urged Microsoft (ticker: MSFT) to scrap its proposed merger with Yahoo! (YHOO) because he felt Microsoft was overpaying. Luckily for Microsoft, Yahoo! rejected the deal, which would have taken place at nearly double the Internet company’s current share price.

Rosenberg doesn’t always get things right. He was bullish on Fannie Mae and bank stocks prior to the financial crisis, during which financial stocks were crushed and Fannie Mae was taken over by the government.

Rosenberg spoke with Barron’s last Monday at his New Jersey home. He’s now bullish on U.S. blue-chips like Microsoft, Merck (MRK) and Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), saying investors have a historic opportunity now to buy them at attractive prices. He believes that Microsoft boss Steve Ballmer should act more like Sam Palmisano, the CEO of IBM (IBM). And he’s bearish on U.S. government bonds—with yields near historic lows. Rosenberg emphasized that these are his own views, and not necessarily those of Loews (L).

Barron’s:Europe has been a big overhang for the U.S. stock market. How bad is it?

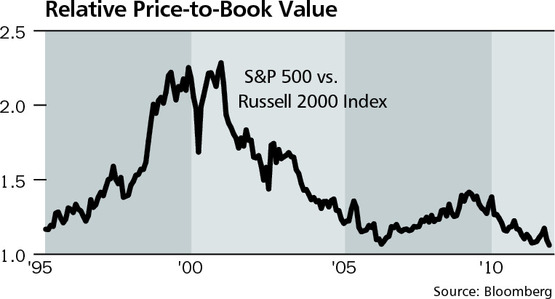

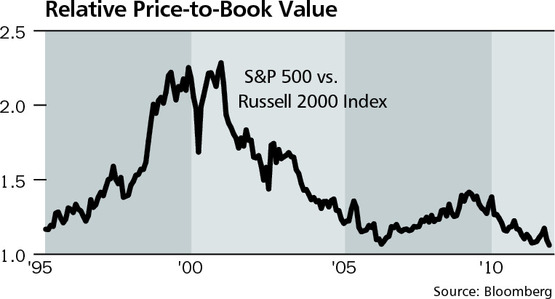

Rosenberg: People are projecting a worst-case scenario about intertwined banking systems in Europe and the United States. That fear factor is what is impelling people to stay away from equities in the United States, and is precisely why equities here are so attractively priced. Now, I am not going to say all equities. There is a big disparity in valuations between the best companies in the world, large-cap companies—both growth and value—and small-cap stocks, which have done well over the past few years, and are not as attractively priced. The price/book ratio of the S&P 500 relative to the Russell 2000 is near a multi-decade low (see graph).

In my 50 years on Wall Street, it is rare that I’ve been so attracted to some of the best and finest companies. I will name a few, but generally speaking, I feel like a kid in a candy store, because I don’t know where to begin. There’s Microsoft, Merck, Amgen [AMGN], Johnson & Johnson, Teva Pharmaceutical [TEVA], Staples [SPLS], Oracle [ORCL] and Cisco [CSCO]. The best companies in the world are now some of the cheapest stocks.

Stocks have disappointed for a long time.

We’re at an inflection point in history, and that’s what I want to emphasize. I’m not talking about a trade. I don’t know what is going to happen next week or next month.

In terms of economic history, the equity market looks a lot like the Treasury-bond market in the early 1980s, when I had the most difficult time convincing people that they ought to buy bonds at 15% yields. Equities can easily generate a 10% annualized total return over the next five to 10 years. And they would still not be overvalued at that point. That’s the beauty of it.

What should investors do?

If investors are afraid to put all their money into equities at one time, keep cash—and then every time you get another one of these scares, add to your position.

Investors are running scared.

These scares are nothing new in financial history. Sometimes, the scares are financial, and sometimes they are political. I can recall worse scares than the current one. Nobody wanted to go near equities during the Cuban missile crisis. That was a much worse scare than this one. It didn’t last as long, but it was much worse, because we were actually on nuclear alert in this country. You can have cheap equity prices or good news, but you can’t have both at the same time.

Many investors are worried that a weakening economy will mean earnings disappointments in 2012.

I think earnings will hold up well next year, but my base case isn’t so much about the short-term earnings outlook.

A lot of the smart money has a very low allocation to U.S. stocks, including university endowments at Harvard, Yale and Princeton.

In the endowment world, everybody wants to be in vogue, so if you suggest to a fund that they ought to buy private equity, they are happy to do that. The wonderful thing about private equity is that you don’t get marked-to-market every day. With stocks, you have to be prepared to suffer some volatility, but the reward for that volatility is the ability to buy companies at prices that are, relatively speaking, as cheap as I have ever seen in my career.

One of my key points is that some of the largest potential investors are all under-invested in equities, and they will get reinvested in equities because these are long cycles. When I first came to Wall Street, the typical pension plan was managed by U.S. Trust, and it would be two-thirds in bonds yielding 2% or 3%, and the rest in equities. That was a carryover from the 1930s and ’40s. It later completely reversed.

Ready to Reverse

Joe Rosenberg likes stocks and is bearish on Treasury bonds, which he thinks are in the final stages of their long bull market.

| Total Returns* |

1-Year

|

5-Year

|

10-Year

|

30-Year

|

| 30-year Treasury |

19.9%

|

10.9%

|

8.7%

|

11.8%

|

| S&P 500 index |

1.1

|

-1.2

|

2.8

|

10.8

|

Change in security value, plus dividends, through Sept. 30

Source: Blanco Research |

Many investors are worried about the political backdrop.

America has loads of problems, but I certainly don’t believe that the country’s best days are behind it. The current administration doesn’t exactly foster a positive environment for the business community, either through its rhetoric or through excessive regulation. But even that has a positive aspect to it. With business leaders so cautious, corporate balance sheets are in superb condition.

How do U.S. stocks compare with other asset classes?

It’s important to look at all investments on a relative basis. One alternative to equities is to earn nothing on your money at all in cash. Now, earning nothing on your money is not without its risks, because your money can prove to be relatively worthless.

The return on government bonds and the return on cash is indistinguishable. It is basically zero. Now, why would somebody want to invest in a five-year Treasury bond at 87 basis points (87/100ths of a percentage point) for five years?

There was a time in the 1980s that I used to scream that people should buy five-year Treasuries yielding 16%, and I would have arguments. People would say to me, “Well, you know, government budget deficits are out of control, and that’s why yields are so high.” Well, if government budget deficits were out of control when Treasuries were paying 16%, what do those same people say to me about government budget deficits being out of control now, when government bonds are paying 87 basis points?

Looking back, bonds have been a great asset class.

The great bond bull market began 30 years ago, in September of 1981. For the past 30 years, 30-year Treasury bonds have outperformed the S&P 500. The last time that phenomenon occurred was in 1842. That is how far back you have to go. Now if you want to look at a period of 20-year outperformance, you have to go back to 1939. While I was around in 1939, I wasn’t managing money actively back then.

How are stocks valued?

Many companies have price/earnings ratios of 10, and free-cash flow yields of 10%. So these companies can basically LBO themselves [do a leveraged buyout] by borrowing two- to three-year money at 2% or 3% and buying an earning asset yielding 10% or more.

So, what’s your advice?

If a person is not a professional and they want equity exposure, one way to get it is buying the SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average ETF [DIA, an exchange-traded fund]. Many of the companies that I would want to own are part of the Dow Industrials.

You’ve been bullish on Microsoft for years, and the stock has gone nowhere. What could change that?

Everyone is talking about IBM, because Berkshire Hathaway [BRKA] took such a large stake in the company. But Microsoft by every metric is better than IBM. Its top-line growth is better. Its valuation is better. Its return on capital is better. Microsoft has a 12-month trailing-earnings yield of 10%; IBM’s is around 7%.

Is Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer part of the problem?

He is focused on operations, and should be focused on that, but he should listen to other people about the capital-allocation process. He should be more aggressive in buying back stock.

There are two things that IBM CEO Sam Palmisano has done, and that Buffett alluded to recently. By the way, I think that Buffett came pretty late to the IBM party. Palmisano basically has laid out a series of five-year plans, and he has met those targets. He also has communicated his intentions and his desires to Wall Street.

In this area, Steve Ballmer has been deficient. He has antagonized Wall Street by his absence. Why should he care about the stock price? His employees are shareholders. A better stock price certainly would help attract young people to work at Microsoft. When people look at a company, they assume that the price of the stock is symptomatic of its success. With Microsoft, that is not the case. Since Buffett is a buddy of [Microsoft Chairman] Bill Gates and has him on the Berkshire board, why doesn’t Buffett tell Gates to take a page out of the success of IBM and apply it to Microsoft?

Microsoft is now around 25. With better capital allocation, where could it trade?

It could easily trade into the 40s. And then things become much easier, because a higher stock price becomes self-fulfilling. There are a lot of reasonable tech stocks: Oracle, Cisco Systems and Hewlett-Packard [HPQ]. I’d also mention the disk-drive industry, with Western Digital [WDC] and Seagate Technology [STX]. The consolidation of that industry means that there are very few competitors, which gives them tremendous pricing power.

Are you partial to drug stocks?

Here’s an industry where dividend yields often are north of 3% and 4%. Companies have spent hundreds of billions of dollars on research and development in the past 10 years, and have little to show for it. Some companies are realizing that, and returning more of their earnings to shareholders. Merck is yielding more than 4%, and selling at a price/earnings multiple of nine, while spending $8 billion a year on R&D. Other companies have similar valuations, including Teva, which is large in generic drugs, and Johnson & Johnson, which is one of the premier companies in the world, has an AAA bond rating, and yields over 3%. Amgen is doing what Microsoft ought to be doing. It just announced a $6 billion bond issue, and a simultaneous repurchase of $5 billion worth of stock.

It’s a Dutch-auction tender. Amgen is going to buy all $5 billion at once.

That’s fine. Amgen isn’t overpaying for the stock, which has a free-cash-flow yield of 9%. Abbott Laboratories [ABT] is attractive, as is Zimmer Holdings [ZMH], which makes hip replacements.

What other stocks appeal to you?

Staples. Here’s an industry that could be consolidating. Staples’ two major competitors– Office Depot [ODP] and OfficeMax [OMX]—can’t seem to get it right. There are ongoing rumors that the two may merge. Staples has a huge brand name, and is very successful. It’s selling with a 10 P/E and a 10% free-cash-flow yield. Staples is handicapped in the short run by what I consider unfair competition in its online business, which is not insignificant. Staples has to charge customers state sales taxes, whereas one of its largest competitors, Amazon.com [AMZN], usually doesn’t. That’s an untenable situation in the long run. If that changes, and I think it will change, it will be a big boost to Staples, which has a better brand name in office supplies than Amazon. [For more on Staples, see “Nope, That Wasn’t Easy.”]

Many value investors like depressed financial stocks. What do you think?

I don’t want to recommend banks. The experience of the past few years has taught me that it’s impossible to figure out what banks own, even when you’re on the inside. As an outsider, I can’t analyze them. This doesn’t apply to MasterCard [MA], but it does apply to Citigroup [C].

How about emerging-market stocks?

I’d rather participate in emerging markets by buying U.S. multinationals that get 50% or more of their revenue abroad, including the growing countries of Asia.

What’s your view on bonds now?

Treasury securities are probably in the final throes of one of the greatest bubbles I have ever seen. But I want to distinguish Treasuries from spread products, such as corporate bonds or Build America bonds—which are taxable municipals—or long-dated municipals. New Jersey recently sold transportation trust fund bonds with a yield above 5%, or 200 basis points more than the 30-year Treasury. That interests me. But I’m not making a bull case for spread products, because equities are so much more attractive.

What about junk bonds?

High-yield debt is not outrageously cheap. I prefer equities.

What are your thoughts on retirement?

When you interviewed me three years ago, I said this and I’ll say it again: Retirement isn’t in my plans. I’m happy working for Loews. I’ll hang around as long as [CEO] Jimmy [Tisch] wants me around.