Be aware of the fragility of companies no matter how powerful today.

Fortune 500 Firms in 1955 vs. 2011; 87% Are Gone.

What do the companies in these three groups have in common?

Group A. American Motors, Studebaker, Detroit Steel, Maytag and National Sugar Refining.

Group B. Boeing, Campbell Soup, Deere, IBM and Whirlpool.

Group C. Cisco, eBay, McDonald’s, Microsoft and Yahoo.

All the companies in Group A were in the Fortune 500 in 1955, but not in 2011.

All the companies in Group B were in the Fortune 500 in both 1955 and 2011.

All the companies in Group C were in the Fortune 500 in 2011, but not 1955.

Comparing the Fortune 500 companies in 1955 and 2011, there are only 67 companies that appear in both lists. In other words, only 13.4% of the Fortune 500 companies in 1955 were still on the list 56 years later in 2011, and almost 87% of the companies have either gone bankrupt, merged, gone private, or still exist but have fallen from the top Fortune 500 companies (ranked by gross revenue). Most of the companies on the list in 1955 are unrecognizable, forgotten companies today. That’s a lot of churning and creative destruction, and it’s probably safe to say that many of today’s Fortune 500 companies will be replaced by new companies in new industries over the next 56 years.

What Causes Corporate Decline According to Steve Jobs

Update: Here’s a related article from Steve Denning in Forbes, featuring some insights from Steve Jobs about what causes great companies to decline (power gradually shifts from engineers and designers to the sales staff) and how the life expectancy of firms in the Fortune 500 and S&P500 has been declining over time.

Also, the impending death of a big-box retailer, Best Buy: http://www.forbes.com/sites/larrydownes/2012/01/02/why-best-buy-is-going-out-of-business-gradually/

Peggy Noonan On Steve Jobs And Why Big Companies Die

There is an arresting moment in Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs in which Jobs speaks at length about his philosophy of business. He’s at the end of his life and is summing things up. His mission, he says, was plain: to “build an enduring company where people were motivated to make great products.” Then he turned to the rise and fall of various businesses. He has a theory about “why decline happens” at great companies: “The company does a great job, innovates and becomes a monopoly or close to it in some field, and then the quality of the product becomes less important. The company starts valuing the great salesman, because they’re the ones who can move the needle on revenues.” So salesmen are put in charge, and product engineers and designers feel demoted: Their efforts are no longer at the white-hot center of the company’s daily life. They “turn off.” IBM [IBM] and Xerox [XRX], Jobs said, faltered in precisely this way. The salesmen who led the companies were smart and eloquent, but “they didn’t know anything about the product.” In the end this can doom a great company, because what consumers want is good products.

Don’t forget the money men

This isn’t quite the whole story. It’s not just the salesmen. It’s also the accountants and the money men who search the firm high and low to find new and ingenious ways to cut costs or even eliminate paying taxes. The activities of these people further dispirit the creators, the product engineers and designers, and also crimp the firm’s ability to add value to its customers. But because the accountants appear to be adding to the firm’s short-term profitability, as a class they are also celebrated and well-rewarded, even as their activities systematically kill the firm’s future.

In this mode, the firm is basically playing defense. Because it’s easier to milk the cash cow than to add new value, the firm not only stops playing offense: it even forgets how to play offense. The firm starts to die.

If the firm is in a quasi-monopoly position, this mode of running the company can sometimes keep on making money for extended periods of time. But basically, the firm is dying, as it continues to dispirit those doing the work and to frustrate its customers.

As the managers find it steadily more difficult to make money playing solely defense, they become progressively more desperate and start doing ever more perilous things, like looting the firm’s pension fund or cutting back on worker benefits or outsourcing production to a foreign country in ways that further destroy the firm’s ability to innovate and compete.

There is another way

What’s interesting is that Steve Jobs lived long enough to show us at Apple [AAPL], in the period 1997-2011: what would happen if the firm opted to keep playing offense and focus totally on adding value for customers? The result? The firm makes tons and tons of money. In fact, much more money than the companies that are milking their cash cows and focused on making money. Other companies like Amazon [AMZN], Salesforce [CRM] and Intuit [INTU] have demonstrated the same phenomenon and shown us that it’s something that any firm can learn. It’s not rocket science. It’s called radical management.

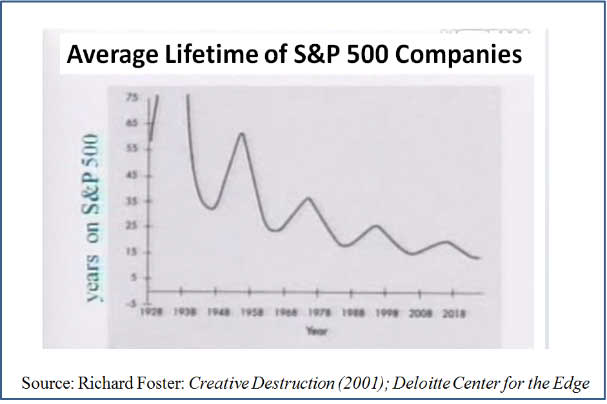

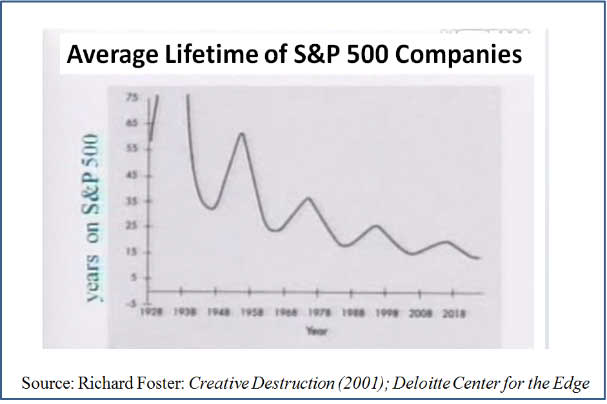

Fifty years ago, “milking the cash cow” could go on for many decades. What’s different today is that globalization and the shift in power in the marketplace from buyer to seller is dramatically shortening the life expectancy of firms that are merely milking their cash cows. Half a century ago, the life expectancy of a firm in the Fortune 500 was around 75 years. Now it’s less than 15 years and declining even further.

The above articles are yellow flashing lights on the longevity of competitive advantage for established companies. Do you agree with the article’s premise?