Yesterday http://wp.me/p1PgpH-MW

I asked what we could do with $100 if held for 25 years. The best performing stock since 1987 is Fastenal (FAST), a nuts and bolts distributor. The high and low for FAST after its IPO in 1987 was 38 to 20 cents. FAST traded at 20 cents after the 1987 crash but let’s say we take a rough mid-point of 30 cents per share. NOT INCLUDING DIVIDENDS, you would have compounded your funds at a 22.2% rate or turned your $100 into $15,000 so far.

Look at the beautiful financials on the above compounding machine: FAST_VL and FAST_MORN. Read the President’s Letters to Shareholders: President’s Letters: http://investor.fastenal.com/letters.cfm. Read the past four letters in sequence 2008 – 2011. Are you clear about what the company does, its goals, strategies and how its management allocates capital?

What’s the point except for hindsight bias and to make us jealous. I was aware of Fastenal during the 2009 crisis but had always dismissed investing in Fastenal due to its “high” P/E multiple. Yet, during 2009, the company kept investing in its operations while the price dropped to 13xs to 14xs normalized non-growth cash flow per share. What would stop the company from growing or taking continuing market share due to its competitive advantages of scale, low-cost, and reach? I missed this opportunity in 2009. Investing is simple, but not easy.

Don’t YOU make the same error. Study great companies so you have an awareness of what greatness is and be ready when opportunity knocks on your door.

Lessons?

But what can you use now to help you find such companies? Buffett once said that compounding was the eighth wonder of the world. http://www.buffettsecrets.com/compound-interest.htm

Companies that can earn high returns on capital while also redeploying capital back into their businesses while continuing to earn high rates are indeed special. Buffett said he understood the chewing gum market (Wrigley) or the soda market (Coke) better than Microsoft (MSFT). Look for businesses doing extraordinary thing in prosaic industries where the need and demand won’t change much while the company can strengthen its competitive advantages through scale and customer captivity.

Articles on Fastenal

http://blogs.hbr.org/taylor/2012/04/to_win_big_it_helps_to_be_a_l.html

To Win Big, It Helps to Be a Little “Nuts”

Wednesday April 18, 2012 |

Here’s a simple question for all you students of business success and stock-market returns: What has been the best-performing stock in the United States since the “Black Monday” crash of 1987? If you said Apple or Microsoft or Walmart or Berkshire Hathaway, you’d get credit for a reasonable answer. But you’d be wrong. The best-performing stock in the United States over the last 25 years is a company that most of you, I’d be willing to guess, have never heard of — a company called Fastenal, based in the quiet town of Winona, Minnesota (population: 28,000), located on the banks of the Mississippi River 30 miles northwest of La Crosse, Wisconsin.

In what glamorous, high-margin, cutting-edge business has Fastenal made its mark? Not software, healthcare, or aerospace. Fastenal is the country’s dominant distributor of nuts and bolts. That’s right…If you’ve got the proverbial screw loose, if you’re a major construction company or a small contractor or individual homeowner desperate for an exotic nut or bolt to complete a job, Fastenal is where you turn.

According to a recent article in Bloomberg BusinessWeek, the company has more than 11,000 sales people in 2,600 stores along with an online catalogue that extends for 10,700 pages. It also has more than 5,500 “fully customized and automated Fastenal stores” on job sites and at customer locations — essentially, vending machines for nuts and bolts. The result of this overwhelming reach is truly overwhelming business performance. According to BusinessWeek, the company’s share price is up 38,565 percent since October 1987. Microsoft, by contrast, is up less than 10,000 percent over that same period (still not bad!), and Apple is up by 5,500 percent.

What’s the lesson to draw from Fastenal’s growth and prosperity? I suppose you could wax rhapsodic about the virtues of low-tech components in a high-tech age, and remind yourself that not every growth company is based in Silicon Valley or some other Internet hotspot. But the real lesson is more universal than that. The Fastenal story reminds all of us of the power of making big bets and staking out an “extreme” position in the market — in this case, offering a wider variety of products through more channels at a greater number of physical and virtual locations than anyone else in the business.

Fastenal has thrived because it has carved out a truly one-of-a-kind presence in its field. As its founder, Bob Kierlin, told BusinessWeek, “It was the craziest thing to ask people to invest in a company selling nuts and bolts” — especially one that aspired to sell anything to anyone virtually anywhere. But as it turns out, if you want to win big, it helps to be a little, ahem, nuts.

That’s a lesson I’ve learned over and over as I’ve studied hugely successful companies in brutally tough industries. It’s just not good anymore to be “pretty good” at everything. The most successful companies figure out how to become the most of something in their field — the most elegant, the most simple, the most exclusive, the most affordable, the most seamless global, the most intensely local. For decades, so many organizations and their leaders got comfortable with strategies and practices that kept them in the “middle of the road” — that’s, in theory, where the customers were, that’s what felt safe and secure. But today, with so much change, so much pressure, so many new ways to do just about everything, the middle of the road has become the road to nowhere.

Just to be clear, being the “most of something” doesn’t have to mean being the biggest or most dominant player in your field. It means being the most deeply committed to a one-of-a-kind strategy and a distinctive presence in a world in which most companies and their leaders are content with doing business more or less like everyone else. As Jim Hightower, the colorful Texas populist, is fond of saying, “There’s nothing in the middle of the road but yellow stripes and dead armadillos.” To which we might add companies and their leaders struggling to stand out from the crowd, even as they play by the same old rules in a crowded marketplace.

One of my favorite bankers in the world, Vernon Hill, who created the one-of-a-kind Commerce Back several decades ago (which he sold to Canada’s TD Bank for a cool $8.5 billion), and is now creating the truly unique Metro Bank in London (the first new bank launched in London in 138 years), has a simple reason for why he strives to become the most of something among banks — in his case, not the biggest, but the most colorful, the most entertaining, the most intensely focused on service and convenience. “Every great company,” he likes to say, “has redefined the business that it’s in. Even though I was trained as a banker, I don’t think like a banker. I do things that conventional bankers think are nutty.”

What goes for nutty bankers goes for retailers selling nuts and bolts. If you want to win big, you have to stand for something special — whether that’s the widest selection and most comprehensive reach, or the most focused offerings and most memorable service. There are countless ways to design the kind of unique profile and strategic presence that Fastenal has in its business and Vernon Hill has in his business. All it requires is a commitment to originality, a willingness to challenge convention and break from standard operating procedure, that remains all-too-rare in business today, precisely because it can look a little “nutty” to the powers-that-be.

If you do business the same way everyone else in your field does business, why would you expect to do any better? So ask yourself: What are you the most of in your business — and how do you become even more of that?

BusinessWeek

According to a recent article in Bloomberg BusinessWeek:

There’s no shame in not knowing the top-performing stock since the crash of ’87. It’s neither Apple (AAPL) nor Microsoft (MSFT), and deprived of the obvious candidates, most people draw a blank. That includes Bob Kierlin. When told that the answer is actually Kierlin’s own company, Winona (Minn.)-based hardware supplier Fastenal (FAST), the 72-year-old founder responds with typical Midwestern understatement: “Oh, wow. Gee. Well, thanks. That’s great news.”

Kierlin, 72, surely knows how well his stock has done: He owns 13.6 million shares, now worth almost $700 million. In the past quarter-century, Fastenal is the biggest gainer among about 400 stocks in the Russell 1000 index that have been trading for at least 25 years, surging 38,565 percent, not including dividends, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Adjusting for splits, the stock has gone from 13¢ on Oct. 19, 1987, to $50.85. It gained 60 percent over the past year.

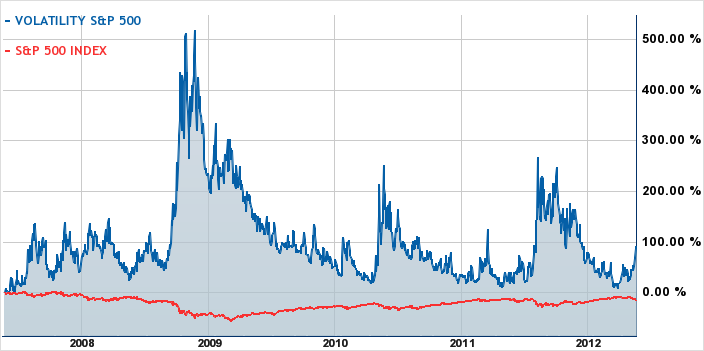

Fastenal edged out UnitedHealth Group (UNH), whose stock gained 37,178 percent and far outstripped Microsoft’s 9,906 percent, Apple’s 5,542 percent, and the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index’s 506 percent. Not bad for a company that literally sells nuts and bolts. “I can understand the disbelief,” says Jonathan Chou, a vice president at mutual fund company T. Rowe Price Group (TROW), which started buying Fastenal stock many years ago and now owns a 12 percent stake in the company.

Chou attributes Fastenal’s success to its stranglehold on the fastener-supply business: There is simply no other distributor that offers so many products in so many locations. The company has 2,600 stores that serve retail and wholesale customers, while its biggest rival, W.W. Grainger (GWW), has 450. Fastenal’s 11,000-plus sales force is technically sophisticated and responsive to customers, Chou says. The company also boasts the kind of scale that allows it to buy hundreds of thousands of items at low-cost from suppliers around the globe.

Fastenal’s website lists 17 categories of fasteners spanning 10,701 pages. Click on bolts, and you’ll see 18 subcategories across 2,471 pages. The breadth of offerings is an almost insurmountable barrier to competitors. “It would be very difficult to replicate this type of product assortment,” says Chou. “The economic moat in this business grows as Fastenal grows.”

While Fastenal’s products may be mundane, companies can’t live without them. “What Fastenal stocks and sells is essential,” says Morningstar (MORN) analyst Basili Alukos. “If you don’t have enough or the right kind, your plant will shut down. Factories are willing to pay a huge convenience premium to a single distributor that can make sure their supply is safe.”

Kierlin says that the idea for a store that offered a vast variety of nuts and bolts—threaded fasteners, as they’re known in the trade—came from his childhood. His father’s auto parts shop was across the street from Winona’s main hardware store. Customers, Kierlin says, kept bouncing between the stores to order hex-cap screws, axle nuts, and cotter pins. In 1967, one year after he returned from a stint with the Peace Corps in Venezuela, that memory inspired him. “Here I’m thinking,” he recalls, “why can’t you have a store that sells everything?”

Originally he thought to sell the fasteners in cigarette pack-size boxes from vending machines placed around town. When he found that no machine could hold enough boxes, Kierlin resolved to raise money to start a conventional store. “It was the craziest thing to ask people to invest in a company selling nuts and bolts,” he says. Even so, Kierlin persuaded four high school friends to chip in a total of $30,000 to found Fastenal. “We didn’t have a lawyer,” he says. “We tried to do it on the cheap.” One of his pals vetoed Kierlin’s preferred name—Lightning Bolts.

Fastenal’s first delivery vehicle was a banged-up Cadillac Coupe de Ville that always veered to the right. The company’s first office desk was a wooden rolltop Kierlin bought for $25 from a laundry that had gone out of business. The original shop had 1,000 square feet on one floor, plus a similarly sized basement (rent was $50 a month) and was lined with kegs that each held 5,000 nuts or screws. When that store filled up, Kierlin rented seven residential garages around Winona and bought 30,000 surplus cardboard toothpaste cartons to hold hardware. “Had you visited our stores in that era,” says Kierlin, “you would have thought we were selling toothpaste rather than fasteners.”

By 1987, Fastenal had 45 stores, mostly in small and midsize towns, and the owners decided to take it public. The stock started trading in August 1987, two months before the market crashed. While the company’s shares fell about 20 percent in the rout, it made up most of that loss by the end of the year. Fastenal had 250 employees at its initial public offering and allocated 100,000 of the offering’s 1 million shares to its employees. Kierlin and his partners also earmarked proceeds to set up an educational foundation for their alma mater, Cotter High School. The company estimates that it provides about $100 million a year to Winona (population 28,000) in employee compensation and dividends paid to local shareholders.

Today, Fastenal has a market value of $15 billion. Net income grew to $358 million in 2011 from $6.4 million in 1990; revenue climbed to $2.77 billion from $52 million. It has stores in all 50 states and has also moved into Mexico, Canada, Central America, Asia, and Europe, often by setting up facilities near U.S. customers that are expanding in those markets. And it finally rolled out a version of that vending machine Kierlin dreamed up 45 years ago, pitching it as a “fully customized and automated Fastenal store within the customer’s location.” Fastenal installed nearly 5,505 of them last year.

None of this means that Fastenal’s stock will keep scorching the market. Charles Carnevale, chief investment officer of EDMP, a money manager in Lutz, Fla., calculates that Fastenal’s shares now trade at 42 times the previous 12 months’ earnings, more than double the company’s expected earnings growth of 19 percent. He also thinks Fastenal’s dividend yield of 1.3 percent is too low. “Fundamentals,” he says, “don’t compensate for the risk.”

That doesn’t bother Kierlin. He says that for all of its success, Fastenal has less than 3 percent of a $150 billion U.S. market, giving it plenty of room to boost sales. And he’s excited that demand for its vending machines is torrid. Fastenal is growing even faster overseas than it is domestically, he adds, so “the best years are still ahead.”

The bottom line: Launched with $30,000, Fastenal has grown into an industry giant with 2,600 stores and a $15 billion market value–over a 5,000 to 1 return so far.

http://investor.fastenal.com/

An educated person is one who has learned that information almost always turns out to be at best incomplete and very often false, misleading, fictitious, mendacious – just dead wrong. –Russell Baker

An educated person is one who has learned that information almost always turns out to be at best incomplete and very often false, misleading, fictitious, mendacious – just dead wrong. –Russell Baker