Readers’ Questions

Rather than email a reply, I thought sharing with other readers might be helpful.

A reader writes: Your emphasis on capital compounders raises a question in my mind. WEB (Buffett) famously said that if he was running a million bucks, he could get returns of 50% per year. If you reverse engineer this statement, you have to think he would be investing in the following: small caps, special situations, and catalysts.

I don’t think you can get those kinds of return with capital compounders. Thoughts?

My response: Good point. By the way, any future questions that you have for Warren can be answered here: http://buffettfaq.com/. An organized web-site of all of Buffett’s articles, writings, and speeches organized by subject, source and date–an excellent resource for Buffaholics. Buffett said he could compound a small amount of money at 50% as he mentions below:

Interviewer to Buffett: According to a business week report published in 1999, you were quoted as saying “it’s a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money. I think I could make you 50% a year on $1 million. No, I know I could. I guarantee that.” First, would you say the same thing today? Second, since that statement infers that you would invest in smaller companies, other than investing in small-caps, what else would you do differently?

Buffett: Yes, I would still say the same thing today. In fact, we are still earning those types of returns on some of our smaller investments. The best decade was the 1950s; I was earning 50% plus returns with small amounts of capital. I could do the same thing today with smaller amounts. It would perhaps even be easier to make that much money in today’s environment because information is easier to access.

You have to turn over a lot of rocks to find those little anomalies. You have to find the companies that are off the map – way off the map. You may find local companies that have nothing wrong with them at all. A company that I found, Western Insurance Securities, was trading for $3/share when it was earning $20/share!! I tried to buy up as much of it as possible. No one will tell you about these businesses. You have to find them.

Other examples: Genesee Valley Gas, public utility trading at a P/E of 2, GEICO, Union Street Railway of New Bedford selling at $30 when $100/share is sitting in cash, high yield position in 2002. No one will tell you about these ideas, you have to find them.

The answer is still yes today that you can still earn extraordinary returns on smaller amounts of capital. For example, I wouldn’t have had to buy issue after issue of different high yield bonds. Having a lot of money to invest forced Berkshire to buy those that were less attractive. With less capital, I could have put all my money into the most attractive issues and really creamed it.

I know more about business and investing today, but my returns have continued to decline since the 50’s. Money gets to be an anchor on performance. At Berkshire’s size, there would be no more than 200 common stocks in the world that we could invest in if we were running a mutual fund or some other kind of investment business.

- Source: Student Visit 2005

- URL: http://boards.fool.com/buffettjayhawk-qa-22736469.aspx?sort=whole#22803680

- Time: May 6, 2005

So the Wizard of Omaha agrees with you that returns are probably to be found in small caps where greater mis-pricing on the downside and upside can occur. The problem you have is paying higher taxes on short-term (less than one year and a day) gains and reinvestment risk. Once you sell you have to be able to find other attractive opportunities to redeploy capital. Special situations like liquidations may give you high annualized returns but the positions may only be held for four months until the investment is liquidated.

Investing in a Coca-Cola may give you high risk adjusted returns but not 50% annual returns because of its side and lack of reinvestment opportunities. Unless you find an emerging franchise which is quite difficult, then if you hold Coke for years, you will eventually earn the company’s return on equity.

This writer organizes his investment world into franchises and non-franchises. With non-franchises you are hoping to buy at enough of a discount to asset value and earnings power value to generate attractive returns. A catalyst like a special situation or corporate restructuring may increase the certainty and lessen the time needed to close the gap between price and your estimate of intrinsic value. Often, with non-franchises you do not have time on your side. You must buy at a huge discount to have a chance at 50% returns. These opportunities may be limited to micro-caps with large discounts partially due to illiquidity issues.

By the way, I am a big fan of small cap special situations, and I plan to post my library for readers, but we have to go step-by-step in posting material.

The reasons I want to focus on franchises are the following:

- A study of franchises will teach us about investing in growth which is difficult to value.

- Studying competitive advantages will hone our skills in business analysis making us better investors.

- Knowing that a company is not a franchise is also important, because–then with no competitive advantage–the company must be managed efficiently. We know what to look for in management activity. Diversification would be a warning signal, for example.

- Investing in franchises can be quite profitable if bought at the right price. Say 3M (MMM) at $42 back in 2009 was purchased, then you would be receiving today about a 5.5% to 6% dividend with growth in cash flows of 8% to 10% or more, then in a few years you will have a 14% dividend yield leaving out any rise in share price. You compound at a low base while you defer taxes and reinvestment headaches. I think Buffett receives double in dividends each year more than the original purchase price of Washington Post. MMM_35

- The biggest gap today in industry and company research is the lack of interest or knowledge in analyzing competitive advantage. Rarely do you ever see an analyst focus on barriers to entry in their valuation work. My hat is off to Morningstar, Inc. because their stock research is geared toward franchises. Many managements have no idea what are structural competitive advantages are. Often, they say their company’s competitive advantage stems from “culture.”

- Finally, you want to avoid Hell. Hell is paying a premium for growth for a non-franchise company. Look at Salesforce.com (“CRM”) as an example for today. Full disclosure: I have held short positions in CRM. Thanks again for your question.

Another reader:

First I would like to thank you for the quality work you are doing. I am new to Austrian economics and I would really appreciate if you can walk us on how to get started and how is it different from other Keynesian and mainstream economics. I, also, want to know why Austrian economics would be more valuable to value investors than other schools. I also wonder why we have not been taught about Austrian economics in school and why it’s not taught.

My reply: Oh boy, you are asking for an all-night discussion. I came out of school having studied Keynesian economics (Samuelson’s text-book, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Samuelson) because that is what American Universities taught back then and still do about economic theory. Imagine studying geography and being told that the world was flat, yet once in the real world ships were circling the globe. What I experienced in real life (raging inflation with high unemployment in the late 1970s) completely contradicted Keynesian theory. Also, the conceit of central planning, having the government intervene, made no sense. How could bureaucrats in Washington, DC allocate resources in Alaska better than an entrepreneur, say, in Alaska? The only economists that predicted the Great Depression and the collapse of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe BEFORE the events occurred were the Austrians, von Mises and Hayek. So I read, Human Action by von Mises, and became hooked. The world of booms and busts, inflation, deflation and capital formation started to make sense. But I had to UNlearn a lot of nonsense.

See how flawed Keynesian prediction has been vs. American history: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XbG6aIUlog. Bernanke in 2005 discussing housing vs. the Austrian view. http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=endscreen&NR=1&v=x2qr5cSln3Q. Bernanke’s confident ignorance is terrifying.

As an investor you must understand how man operates in an economy allocating scarce resources to better his condition or lesson his unease. Only Austrians–from what I know–have a coherent theory of the business cycle and the structure of production. But then you may ask, “If Keynesianism is such a repeated failure, then how come it is still prevalent today?” Think of human motivation. If you are a politician, what better cover to weld power than Keynesian theory? Constant intervention to “help” is your guide.

Successful investors who are considered Austrians because they study/follow the precepts of Austrian Economics): http://www.dailystocks.com/forum/showtopic.php?tid/2623

Noted investors who use Austrian Economics:

George Soros is the legendary investor who started Quantum Fund in the 1960s and is a multi-billionaire as a result of some winning macro trades. Soros’ prescription for healing broken economies cannot be mistaken for Austrian Economics, but Soros’ analysis of markets as expressed in his books seems to borrow a lot of influence from the Austrian Economists.

Jim Rogers is acknowledged as one of the most successful investors of all time. Making an early start when he was in his twenties, he was able to build a huge fortune with an initial investment of just $600 by the time he was 37. A firm believer in Austrian economics, he advocates investing in China, Uruguay and Mongolia.

Marc Faber was born in Switzerland and received his PhD in Economics from the University of Zurich at age 24. He was Managing Director at Drexel Burnham Lambert from 1978-1990, and continues to reside in Hong Kong. He is famed for his insights into the Asian markets, and his timely warning about market crashes earned him the name of Dr.Doom. In 1987 he warned his clients to cash out before Black Monday hit Wall Street. In 1990 he predicted the bursting of the Japanese bubble. In 1993 he anticipated the collapse of U.S. gaming stocks and foretold the Asia Pacific Crisis of 1997-98. A contrarian at heart, his credo has always been: “Follow the course opposite to custom and you will almost always be right.”

James Grant, a newsletter writer who publishes “Grant’s Interest Rate Observer” is also a follower of Austrian Economics. He is a “Graham & Dodder” too. Go to www.grantspub.com

Ron Paul, a Republican Congressman for the Texas State, is also a believer of Austrian Economics.

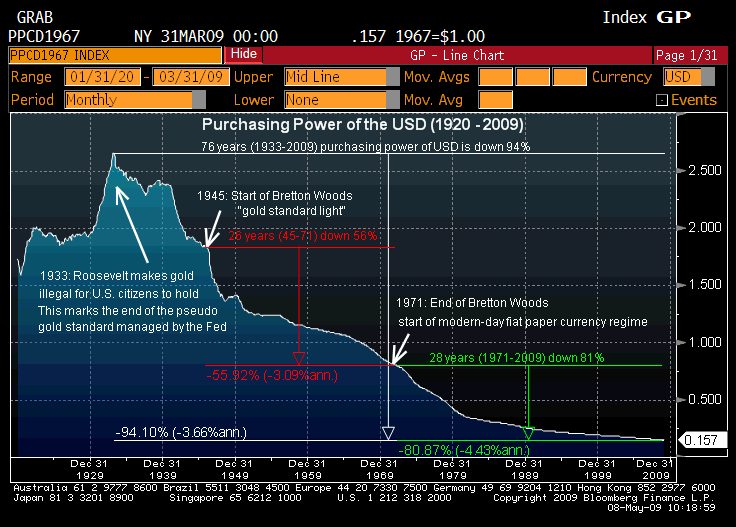

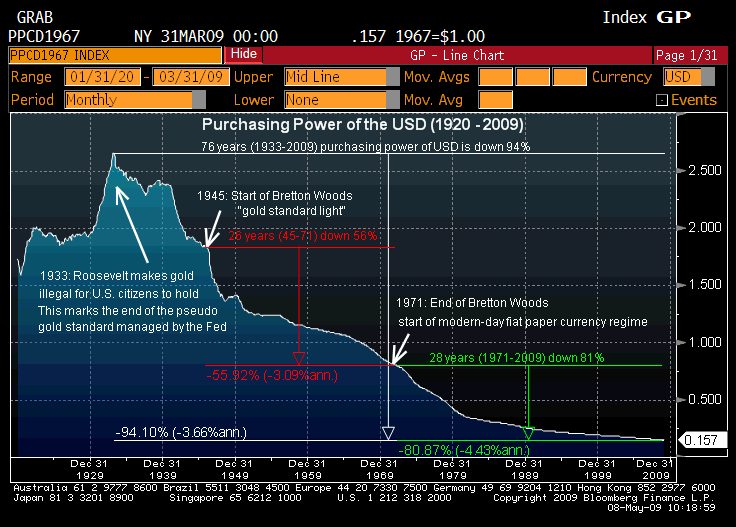

Interestingly enough, Howard Buffett, the father of Warren Buffett is also an Austrian Economics follower. His son, Warren, however, seems to be more inclined to the Keynesian method of healing broken economies as opposed to the strict and rigid ones espoused by Austrian economists. Warren Buffett did acknowledge in a recent TV interview that one will have a hard time finding a paper based currency that appreciates in value over time. (All fiat currencies have been debased to worthlessness.)

Austrian Economics vs. Keynesianism

What is Austrian Economics http://mises.org/etexts/austrian.asp

http://mises.org/daily/4095 Hayek vs. Keynes Rap video and discussion. http://mises.org/daily/3465 The Austrian Recipe vs. Keynesian Fantasy.

A recent civil debate between an Austrian economist and a New Age Keynesian. http://board.freedomainradio.com/forums/t/32178.aspx

Free School in Austrian Economics

If you REALLY want to learn Austrian economics, the lessons couldn’t be laid out better for you than here: http://www.tomwoods.com/learn-austrian-economics/. Start with Economics in One Lesson by Hazlitt.

And if you want to interact with professors you can go to the Mises Academy here: http://academy.mises.org/. Don’t go by what I say, but by what YOU think after delving into the material. Does it make sense? Forget political labels of Right-wing, Democrat, Liberal, and Conservative; think of how the world works. I hope that helps partially answer your question.

The same reader asks another question:

I have another question related to Bruce Greenwald book, Competition Demystified. In his book he mentioned that if the company has no competitive advantage then strategy is irrelevant and the course of action should be efficiency. However, following this argument, investors would have avoided many companies during the journey to become industry dominant player.

Correct me if mistaken, but I don’t think you have read the entire book yet. Greenwald will talk about entrant strategies from the point of view of the incumbent (crush an entrant) to an entrant (how to gain a foothold profitably against an incumbent). Greenwald will also talk about cooperation between incumbents.

If you want a more detailed description of emerging franchises–though I suggest you read it after Greenwald’s book–read Hidden Champions of the 21st Century by Hermann Simon.

I can promise you that one of the reasons for Buffett’s success is his amazing understanding of competitive advantages in his investments. As a business person understanding strategy is critical.

Here is a question. You own a chain of very profitable movie theaters within a 150 mile radius of a major city. These theatres are spread about 5 to 20 miles from each other and are nicely profitable. You have economies of scale in hiring, securing first-run films, buying condiments, etc. You awake one morning to find that another large regional theater chain from 800 miles away wants to open a theatre near one of your 29 theatres. What response might you offer to send a strong message not to enter this market? A paragraph is enough.

Thanks for your questions, you make me work hard.