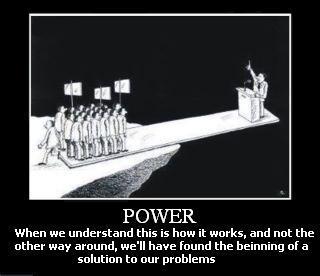

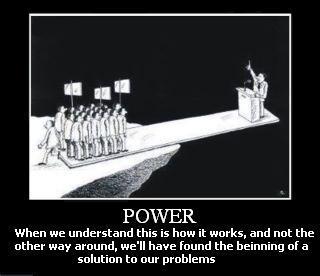

”I do not ask that you place hands upon the tyrant to topple him over, but simply that you support him no longer; then you will behold him, like a great Colossus whose pedestal has been pulled away, fall of his own weight and break in pieces.” -Étienne de La Boétie

Fiat Currency

Do you see any flaws in the author’s argument. If not, then read the next article on the Economics of a P.O.W camp.

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/02/a-short-history-of-american-money-from-fur-to-fiat/252620/

What do animal pelts, tobacco, fake wampum, gold, and cotton-paper bank notes have in common? At one point or another, they’ve all stood for the same thing: U.S. currency.

IN DOLLARS WE TRUST

The dollar, meanwhile, remained the anchor currency of the world: the one ring that kinda rules them all. Other governments hold on to dollars and use them for paying debts, and in the aisles of the global supermarket of goods, most items are priced in U.S. dollars.

This is what’s so weird about commentators in the U.S. proudly declaring that the dollar is the most stable currency in the world, as if this were because of American economic policy today, when it’s really just the result of negotiations a few generations ago that made it the backbone of the whole system. The greenback is stable because the U.S. economy is huge and the United States is a terrific republic–OK. But it’s also stable because everyone else’s well-being depends on it, and on belief in its stability. That may be changing, though.

As for paper money itself, the end of the gold standard meant that cash had become a total abstraction. Its value now comes from fiat, government mandate. It’s a Latin word meaning let there be. In God we better trust.

From The End of Money: Counterfeiters, Preachers, Techies, Dreamers–and the Coming Cashless Society by David Wolman. Reprinted courtesy of Da Capo Press.

The Economics of a P.O.W. Camp

http://mindhacks.com/2008/07/06/the-economics-of-a-prisoner-of-war-camp/ and PDF article here (excellent!) http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~hfoad/e111su08/Radford.pdf

Commodity money is money whose value comes from a commodity out of which it is made. It is objects that have value in themselves as well as for use as money.[1]

Examples of commodities that have been used as mediums of exchange include gold, silver, copper, peppercorns, large stones (such as Rai stones), decorated belts, shells, alcohol, cigarettes, cannabis, candy, barley etc. These items were sometimes used in a metric of perceived value in conjunction to one another, in various commodity valuation or price system economies.

Commodity money is to be distinguished from representative money which is a certificate or token which can be exchanged for the underlying commodity, but only as the trade is good for that source and the product. A key feature of commodity money is that the value is directly perceived by the users of this money, who recognize the utility or beauty of the tokens as they would recognize the goods themselves. That is, the effect of holding a token for a barrel of oil must be the same economically as actually having the barrel at hand. This thinking guides the modern commodity markets, although they use a sophisticated range of financial instruments that are more than one-to-one representations of units of a given type of commodity.

Since payment by commodity generally provides a useful good, commodity money is similar to barter, but is distinguishable from it in having a single recognized unit of exchange. (Radford 1945) described the establishment of commodity money in P.O.W camps

Logic Course

To learn more about avoiding fallacious thinking* take a course in logic from an outstanding professor, David Gordon. I have taken this course–recommended for those who have never taken logic. http://academy.mises.org/courses/logic/

Baseless Assertions

The author in the first article makes an assertion without logic or evidence to back up the statement. Money doesn’t have value just because the government says it does. Obvious proof of that is the German Hyper-Inflation in the 1920s when the currency went to worthlessness. A monetary crack-up.