We first discussed Apple (AAPL) here: http://wp.me/p2OaYY-1Fi

As a reader made clear on our prior post on Apple, anticipating or foreseeing Apple’s stupendous success would take insight, knowledge and clairvoyance that few–especially this writer–possess. So what’s the point? Can we learn anything to add to our skills?

Well, we can compare Apple to other great innovations like the first mass-produced car, the Ford Model-T. We can look at technology companies that lost their genius founder like Polaroid and compare and contrast with Apple. Also, we can look at the expectations the market had for Apple vs. the law of large numbers–the huge size of the company, its huge dominance of an important, growing market that made the odds of maintaining its current rate of success vs. expectations quite low.

When expectations are high for already outstanding success we need look no further than the Nifty Fifty for what can happen. Please read:The Delusions of High Growth Expectations and valuing-growth-stocks-revisiting-the-nifty-fifty .

Here is an excellent article from the Wall Street Journal discussing Apple in historical perspective: WSJ_Apple.

I will be building my case file on Apple including past annual reports. If readers come across anything pertaining to Apple or other companies in the same context, please alert me and I will post and add to the case file. Everyday there are lessons to be had, but I chose Apple for its sheer influence on our daily lives.

THANKS!

Update Feb. 8, 2013

Following a Herd of Bulls on Apple By JAMES B. STEWART

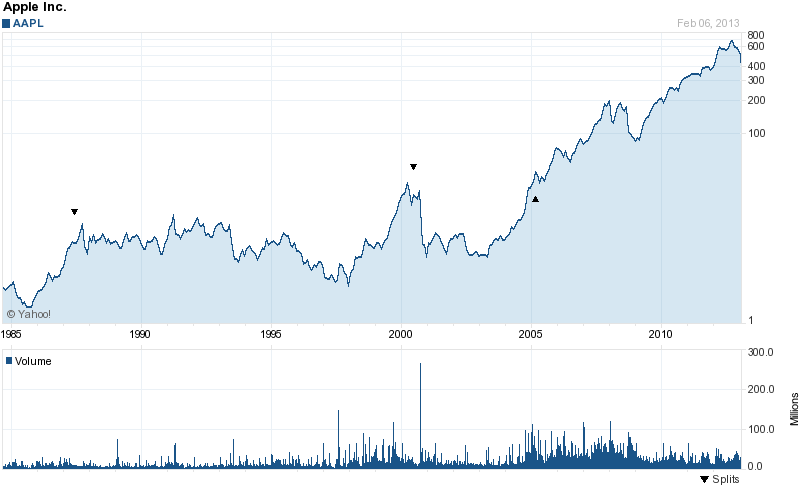

Last September, Apple shares hit a record $705. And to the overwhelming majority of Wall Street analysts, that meant one thing: buy.

By November, with Apple stock in the midst of a precipitous decline, they were still bullish. Fifty of 57 analysts rated it a buy or strong buy; only two rated it a sell. Apple shares continued their plunge, and this week were trading at just over $450, down 36 percent from their peak.

How could professional analysts have gotten it so wrong?

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. A decade ago, Congressional hearings and an investigation by Eliot Spitzer, then the New York attorney general, exposed a maze of conflicts of interest afflicting Wall Street research. There were some notorious examples of analysts who curried favor with investment banking clients and potential clients by producing favorable research, and then were paid huge bonuses out of investment banking fees. Many investors and regulators blamed analysts’ overly bullish forecasts for helping to inflate the dot-com bubble that burst in 2000.

After a global settlement of Mr. Spitzer’s investigation by major investment banks and the Sarbanes-Oxley reform legislation in 2002, investment banking and research operations were segregated. Conflicts had to be disclosed, and research and analyst pay was detached from investment banking revenues, among other measures.

These reforms seem to have worked — but only up to a point. Other conflicts have come to the fore, especially at large brokerage firms and investment banks. And studies have shown that analysts are prone to other influences — like following the herd — that can undermine their judgments. “The reforms didn’t necessarily make analysts better at their jobs,” said Stuart C. Gilson, a professor of finance at Harvard Business School.

It may be no coincidence that the only analyst who even came close to calling the peak in Apple’s stock runs his own firm and is compensated based on the accuracy of his calls. Carlo R. Besenius, founder and chief executive of Creative Global Investments, downgraded Apple to sell last Oct. 3, with shares trading at $685. In December, he lowered his price target to $420, and this week he told me he may drop it even further, to $320.

Mr. Besenius founded his firm a decade ago after spending many years in research at Merrill Lynch and Lehman Brothers. “I saw so many conflicts of interest in trading, investment banking and research, so I started a conflict-free company,” he said this week from Luxembourg, where he was born and now lives. “Wall Street is full of conflicts. It still is and always will be. It’s incompetent at picking stocks.”

Since the passage of Sarbanes-Oxley, several studies have documented a decline in the percentage of analysts’ buy recommendations, albeit a modest one, while sell recommendations have increased. “Before 2002, analyst recommendations were tilted toward optimistic at an extreme rate,” Ohad Kadan, a professor of finance at Washington University in St. Louis, and co-author of one of the studies, told me this week. “That’s still true today, but it’s not as extreme. It’s a little more balanced.”

While investment banking conflicts have been addressed, “the most obvious conflict now is that research is funded through the trading desks,” Professor Gilson said. “If you’re an analyst and one way your report brings in revenue is through increased trading, a buy recommendation will do this more than a sell. For a sell, you have to already own the stock to generate a trade. But anybody can potentially buy a stock. That’s one hypothesis about why you still see a disproportionate number of buy recommendations.” That may be especially true for heavily traded stocks like Apple, which generate huge commissions for Wall Street.

But no one thinks conflicts alone can explain the analysts’ abysmal recent Apple performance. “There’s too much unanimity,” Bruce Greenwald, a professor of finance and asset management at Columbia Business School and a renowned value investor, told me this week. “That’s what’s so troubling. When that many analysts are in agreement, they can’t all be conflicted.”

He and other experts say there are additional documented factors that help explain why Wall Street analysts are so often wrong: they extrapolate from recent performance data; they chase momentum; they want to please their customers; and they show a tendency toward herd behavior. Which is to say, they fall into the same pitfalls that afflict most investors.

“Why aren’t they more sophisticated? You’d hope they would be,” Professor Kadan said. “But they always fall into the same traps.”

Professor Greenwald agreed. “When something goes up, they all put out buy recommendations. Their models extrapolate past performance into the future. They chase momentum. With Apple, they were right at $600, and they were right at $650, which reinforced the trend. So why would they be wrong at $700?”

Professor Kadan said that momentum investing has its adherents, and is often right, at least in the short term that many investors focus on. “You’d hope that analysts, of all people, would be able to anticipate an abrupt reversal, but they’re not very good at it. They loved Apple at $700. I’m sure they were trying to do their best, but they’re prisoners of momentum.”

Another factor is that analysts have a tendency to tell their audience what it wants to hear. “The analysts are in the end sales people,” Professor Greenwald said. “Their credibility depends on their not upsetting their investors too much. Everybody loved Apple, everybody did well. The bears were always wrong. It took an enormous amount of courage to fight the tide.”

Professor Kadan agreed. “Analysts tend to herd. There’s no big penalty if you’re wrong, because everyone else is wrong. You’ve got cover. You’re not going to lose your job. If you take a different opinion, either you get a big prize if you’re right, or you lose your job. An analyst needs to be really courageous to say something different from most other analysts.”

Mr. Besenius, the one analyst who downgraded Apple near its peak, said, “I’m not afraid to make big, controversial calls,” but attributed his decision less to courage than to survival. “I’m paid based on performance,” he said. “I have to go to my clients and explain why they should pay for my research when they can get it for nothing from the firms where they pay their trading commissions.”

Mr. Besenius based his recommendation on technical factors — as Apple hit $700, its upward momentum and trading volume were slowing — as well as more fundamental concerns about product quality and innovation, as well as growing competition from rivals like Samsung. And there were more subjective factors. Mr. Besenius said he became uncomfortable with what he deemed Apple’s arrogance. “I loved Steve Jobs,” he said. “He built a great company. But he was one of the most arrogant C.E.O.’s I’ve ever met. The way he introduced new products was one big display of arrogance. He ridiculed Microsoft as ‘Micro who?’ That’s a good reason to be cautious. A little humility is a good thing.” (An Apple spokesman declined to comment on Mr. Besenius’s observations.)

It galls Mr. Besenius that market regulators don’t measure the performance of Wall Street’s research recommendations, and he said he believed that they should require firms to disclose the track records of stocks their analysts recommend. “They’re not being held accountable” for bad recommendations, he maintained. “Little firms like ours have to be better than the big firms. We have to prove we can add value. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have an existence.”

Apple is only one prominent example of egg on analysts’ faces, and bullish Wall Street analysts were right for years — until they were wrong. Even today, analysts remain overwhelmingly positive about Apple. This week, 44 analysts rated it a strong buy or buy, although 10 now rate it a hold, according to Thomson Reuters.

Should anyone listen?

Many brokers still rely on their analysts’ research, and offer the analysts’ reports to clients for guidance in picking stocks to buy and sell. But the Securities and Exchange Commission takes a skeptical approach. Despite the reforms it helped put in place, it warns on its Web site of continuing conflicts of interest and says flatly, “As a general matter, investors should not rely solely on an analyst’s recommendation when deciding whether to buy, hold, or sell a stock.” It notes that many brokers aren’t allowed to contradict recommendations from their own research departments.

Professor Gilson of Harvard said: “Analysts are like movie critics. Some are good and some are bad. I find some of them extraordinarily useful. I advise my students to look to them, but you have to read their recommendations smartly with a very critical eye.”

Professor Greenwald was more dismissive. “I never pay attention to them, “ he said. “When a dog barks, if the dog barks all the time, you stop paying