Cooperman’s discussion of a Great Capital Allocator, Henry Singleton of Teledyne:Teledyne and Henry Singleton a CS of a Great Capital Allocator

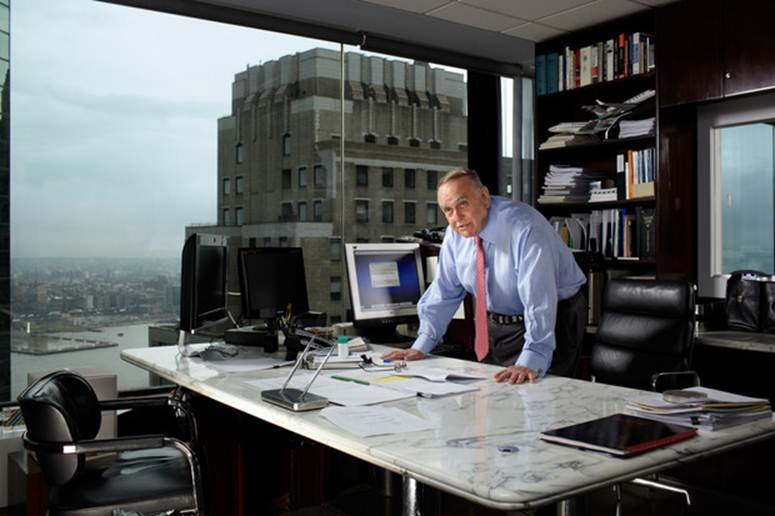

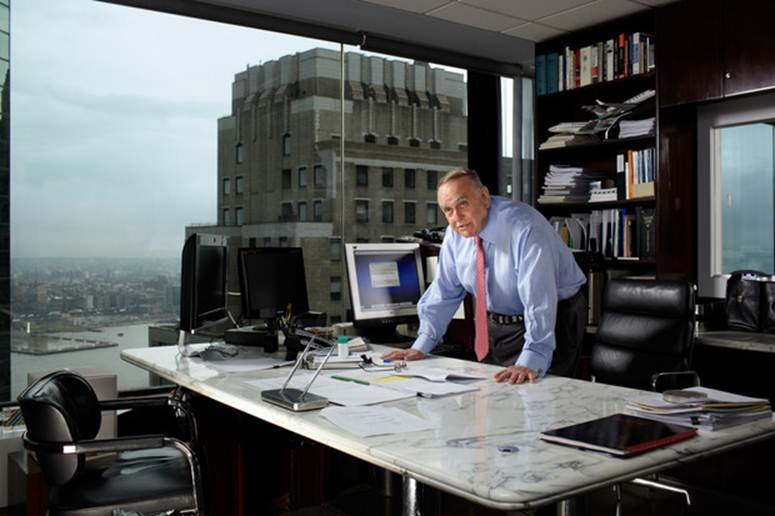

June 28 (Bloomberg) — Leon Cooperman, chief executive officer of hedge fund Omega Advisors Inc., talks about his investment strategy, stock picks and the outlook for global economies. The story is featured in the August issue of Bloomberg Markets magazine. (Source: Bloomberg)

“The market is very sick,” Cooperman says. That’s not necessarily bad news for Cooperman, 69, a blustery billionaire from the South Bronx who first made his name as a stock picker during 25 years as an analyst atGoldman Sachs Group Inc. (GS) “We have to take advantage,” he says. “What’s ridiculously priced now?”

Omega, which currently invests its $6 billion in assets mainly in U.S. stocks, has returned an average of 13.3 percent annually since Cooperman founded it in 1991, compared with 11.4 percent for other equity-oriented funds, according to Chicago- based Hedge Fund Research Inc., Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its August issue.

For more than 40 years, Cooperman has earned a reputation for consistently ferreting out the most-discounted stocks — no matter what the overall market conditions.

“He’s not doing anything terribly fancy; he’s looking for stocks that are undervalued,” says Robert S. Salomon Jr., 75, an Omega client whose grandfather co-founded Salomon Brothers. “He’s had some great success in finding them.” Adds John Whitehead, 90, who was co-chairman of Goldman during Cooperman’s time there, “He’s been around a long time and seen bad markets and good markets, and he’s survived them all successfully.”

Euro Fears

Markets on this particular day in May are being buffeted by fears about the future of the euro region, the possibility of U.S. tax cuts expiring at the end of 2012 and slowing growth in China. After the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index tumbled 6 percent in May, some money managers bet that the market would fall further. John Burbank, who runs the $3.4 billion Passport Capital LLC hedge fund, told Bloomberg News that he’s shorting stocks because he expects the U.S. and much of the rest of the world to fall back into a recession.

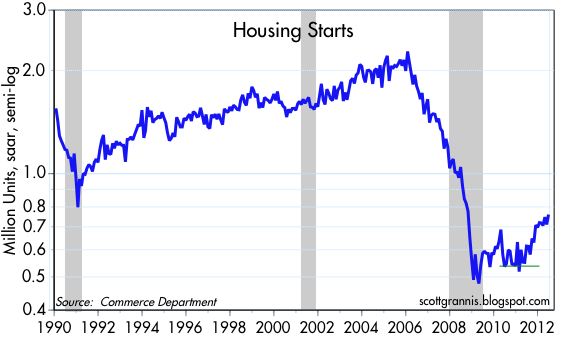

Cooperman is more sanguine about the future. As of June 11, his fund was up 6 percent this year–compared with 1.03 percent for hedge funds globally. He says stocks offer the best opportunities for investors, particularly in the U.S., where there are no signs of a recession. Banks are more profitable, household debt has declined and companies are increasing capital spending.

Stocks Undervalued

Yet stocks have remained undervalued, he says, because of economic troubles and uncertainty over the U.S. presidential election. TheS&P 500 (SPX) is trading at a price-earnings ratio of 12.5 compared with an average of 15 during the past 50 years.

“Stocks are the best house in the financial asset neighborhood,” Cooperman says, before adding a caveat: “It’s not clear whether it’s a good neighborhood or a bad neighborhood.”

Filling a large room in Cooperman’s investing house today is student loan providerSLM Corp. (SLM), better known asSallie Mae. With total educational debt in the U.S. ballooning to $904 billion as of March 31 from $241 billion a decade earlier, according to theFederal Reserve Bank of New York, some commentators have talked about a looming student-debt crisis.

Cooperman sees an opportunity. Sallie Mae throws off lots of cash, he says. Some 80 percent of its loans outstanding consist of government-backed debt issued before 2010, when Congress mandated that the government make certain college loans directly rather than subcontracting them to Sallie Mae. Since then, Sallie Mae has been expanding its private lending business, charging free-market rates that can run as high as 12.88 percent.

‘Kids Have to Borrow’

Cooperman started buying Sallie Mae in December 2007, after a $25 billion buyout deal with J.C. Flowers & Co.,JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM) andBank of America Corp. collapsed amid the credit crisis, sending its shares plummeting. On April 21, 2011, the company announced that it would reinstate its dividend, sending the shares up 13 percent to $16.13. Cooperman paid an average of $7.36. SLM closed at $15.20 on Wednesday, and Omega predicts that it will rise as high as $22. Omega is the eighth-largest owner of the company, with a 3.51 percent stake.

“Ultimately, it’ll work,” Cooperman says of SLM. “Lots of kids have to borrow money; their parents have to cosign the loans. It’s a profitable business.”

JPMorgan Loss

Not all of his bets work out. Omega had considered JPMorgan Chief Executive OfficerJamie Dimon the best in the industry, and the bank’s management had been aggressively repurchasing stock. Omega started buying shares of the New York bank in 2009 at an average cost of $37.14.

JPMorgan disclosed on May 10 that it had a $2 billion trading loss because of riskier-than-expected credit securities. Omega sold about two-thirds of its position the next day, taking a loss: The shares tumbled 9 percent on May 11, closing at $36.96. They traded at $36.78 yesterday.

At Omega’s staff meeting in May, one of the portfolio managers suggests that JPMorgan shares may now be ridiculously cheap. Cooperman launches into a tirade about how Dimon has been unfairly pilloried by Representative Barney Frank and other critics. “I’m incensed by some of the sh– you’re reading,” Cooperman tells his managers. He says he’ll hold on to his remaining shares as a vote of confidence in Dimon. Cooperman, a self-described workaholic, says there’s no magic formula to finding good stocks.

Sailing and Research

“With an average IQ and a strong work ethic, you can go far,” he says, adding that he sees himself as proof of that. “I don’t have a lot of outside interests. I don’t do well with leisure. I like a structured life.”

Cooperman expects stocks to return 7 to 8 percent in the future, below their historic 10 percent returns.

Barry Rosenstein, co-founder of the $3 billion Jana Partners LLC hedge fund in New York, admires Cooperman’s work ethic. Rosenstein was a teenager when he first met the fund manager at a sailing club on the Jersey Shore of which both were members. Cooperman would show up with a stack of annual reports, disappear onto his boat and read them all weekend, Rosenstein, 53, recalls.

“If Bruce Springsteen is the hardest-working man in rock ’n’ roll, Lee is the hardest-working man in the investment business,” he says. Cooperman was one of the first to invest in Jana when Rosenstein founded it in 2001.

Share Buybacks

As he scours reports and quizzes executives on earnings calls and at conferences, Cooperman is trying to discover stocks that have a low price-earnings ratio, lots of cash and decent yields and that are trading for less than their net assets are worth. He also looks for what he calls smart managers who own big stakes in their companies and for firms that buy back their own shares cheaply.

While he was at Goldman, one such hit was what’s now called Teledyne Technologies Inc. (TDY), whose founder, Henry Singleton, made acquisitions using the company’s stock when its price was high. When the share price went down, Singleton bought back shares repeatedly. Under Singleton, Teledyne expanded its defense, aerospace and industrial businesses. Cooperman recommended the stock in 1968, and for the following two decades, it generated a 23 percent annual return. Cooperman displays a framed 1982 letter in his office fromWarren Buffett congratulating him on his analysis of Teledyne.

Betting on Apple

One of Cooperman’s largest holdings today is Apple Inc. (AAPL), which Omega portfolio manager Barry Stewart says he likes because of its $110 billion cash hoard. Apple’s prospects for growth are strong, he says, with the market booming for its iPhone smartphones, MacBook computers and iPad tablets.

Cooperman pounced on the stock at an average of $376 a share starting in July 2010, around the timeConsumer Reports said a faulty iPhone 4 antenna could cause the phone to lose its signal. The problem proved to be a hiccup, and Apple shares have since risen to $574.60. Stewart projects that the stock will go as high as $710 in the next year.

Stewart is also betting that growing demand for 3G and 4G mobile phones made by Apple and others such as Samsung Electronics Co. will boost the fortunes ofQualcomm Inc. (QCOM), the largest producer of semiconductor chips for the devices. Omega began buying Qualcomm last August at an average price of $53. The shares traded at $54.91 on Wednesday, and Stewart says they could rise as high as $85 in the next 12 months.

Smart Management

One of Cooperman’s worst-performing holdings this year is McMoRan Exploration Co. (MMR), an oil-and-gas drilling company whose price plunged about 40 percent from a high of $14.55 on Dec. 30 after an equipment malfunction caused delays at one of its wells in the Gulf of Mexico. Cooperman is still enthusiastic about its prospects because it meets his requirement of smart management.

James “Jim Bob” Moffett, the New Orleans-based company’s CEO, is also chairman ofFreeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. (FCX), the world’s largest publicly traded copper producer, and has a track record of making deals in far-flung places. McMoRan formed a joint venture with Chevron Corp. (CVX) to drill for oil in Louisiana. Omega paid $10 on average for the shares, which traded at $12.30 on Wednesday. If the company strikes oil, Omega predicts that the stock could reach $25 to $30 within 18 months.

When a company considers its own stock a bargain, Cooperman wants in too. That was the case withAmerican International Group Inc. (AIG), the New York-based insurer majority owned by the U.S. government after its 2008 bailout. CEO Robert Benmosche has bought back shares from the U.S. Treasury and repaid funds tied to AIG’s government bailout.

When a company considers its own stock a bargain, Cooperman wants in too. That was the case withAmerican International Group Inc. (AIG), the New York-based insurer majority owned by the U.S. government after its 2008 bailout. CEO Robert Benmosche has bought back shares from the U.S. Treasury and repaid funds tied to AIG’s government bailout.

Lane Bryant

The company bought $3 billion of its stock in March, and $15 billion of planned asset sales should fuel more buybacks, Omega portfolio manager Mahmood Reza says. Omega bought the shares this year for an average of $30.47 and anticipates that the price could rise to $53 by the end of 2013. They traded at $30.82 on Wednesday.

Cooperman also hunts for takeover candidates. Omega zeroed in on Charming Shoppes Inc., the owner of plus-size-clothing retailer Lane Bryant, after visiting the company’s executives. The company’s cash exceeded debt and had the potential for higher profitability as part of a bigger group.

He started buying the shares at less than $3 each last year and added to his position after David Jaffe, CEO ofAscena Retail Group Inc. (ASNA), formerly known as Dress Barn Inc., told a conference that he was interested in buying companies. Omega amassed a 13 percent stake in Charming Shoppes. In May of this year, Ascena agreed to buy the company for $7.35 a share.

Azerbaijan Deal

In 1998, Cooperman bet big on emerging markets — and lost. The misstep was compounded by Omega’s investment of more than $100 million with Czech financierViktor Kozeny in a plan to take over Azerbaijan’s state oil company. New York state prosecutors accuse Kozeny, who now lives in the Bahamas, of stealing Cooperman’s investment, while U.S. prosecutors say Kozeny led a multibillion-dollar bribery scheme in connection with the Azeri deal.

In 2007, Omega paid $500,000 to the U.S. to resolve the – bribery investigation. Omega didn’t admit wrongdoing while it accepted legal responsibility for the actions of an employee who admitted joining Kozeny’s bribery scheme. Kozeny denies wrongdoing.

In all, Omega lost a total of $500 million, or 13 percent of its total assets in 1998, after which Cooperman fired almost the entire emerging-markets team. (He later recovered some of the money.) He says the episode was the worst chapter of his life.

Goldman Career

The younger of two sons of Polish immigrants, Cooperman bagged fruit and changed tires to make money as a teenager in the Bronx. He learned how to analyze securities from the late Roger Murray, a professor at Columbia Business School. Another professor’s recommendation earned Cooperman a job as a research analyst at Goldman.

Cooperman’s office is filled with mementos of his years at Goldman, for which he still manages an undisclosed amount of money. A framed copy of the company’s business principles is displayed in Cooperman’s office, near a curled-up whip — a gift from Goldman salesmen after he completed a 30-city, 20-day roadshow to market a stock fund in 1990. After years in research, Cooperman founded Goldman Sachs Asset Management in 1989.

Despite being a billionaire, Cooperman, who has three grandchildren, says he has no plans to retire soon. “He’s the first one in the office, the last one out,” says Tomas Arlia, head of hedge funds at GE Asset Management Inc., which has had money with Omega since its inception. “He loves what he does.”

A piece of paper taped to his computer monitor reminds Cooperman of the simple investing rules that have helped Omega weather market storms for the past two decades: “Buy low, sell high, cut your losses, let your profits run.”