“We Are All Doing The Same Thing”

I recently listened to a podcast with some all-star [there are awards for everything now] “Black Box” equity trader. It was quite a “telling” interview & I thank him for his insights but I’d heard it all before. His confidence was staggering considering the general unpredictability of the future and, of course, the equity markets. He explained how he had completely converted from a generally unsuccessful, discretionary technical trading style to a purely quantitative and scientific trading mode. He seemed to be so excited that his models, according to him, were pretty much “bullet proof”. Having had more than just some tangential experience with black box modeling and trading myself I thought … you know … some people will just never learn.

Image via iwatchapple.it

You see some years ago I was particularly focused on quantitative investing. Basically, “screw” the fundamentals and exclusively concentrate on price trends/charts and cross security/asset correlations [aka “Black Box” trading]. I was fascinated with the process and my results were initially stellar [high absolute returns with Sharpe Ratios > 2.0]. And, after looking at the regression data many others agreed. I was in high demand. So I “made the rounds” in Manhattan and Greenwich to a group of high profile hedge funds. It was a very exciting time for me as the interest level was significant.

As it turned out I had the good fortune of working with one of the world’s largest and best performing hedge funds. Their black box modeling team had been at it for years … back-testing every conceivable variable from every perceived angle … twisted/contorted in every conceivable/measurable manner … truly dedicated to the idea that regression tested, quantitative trading models were the incremental/necessary “edge” to consistently generate alpha while maximizing risk-adjusted, absolutely positive returns. We worked together for some time and I became intimately involved with their quantitative modeling/trading team … truly populated with some of the best minds in the business.

While in Greenwich Ct. one afternoon I will never forget a conversation I had with a leading quantitative portfolio manager. He said to me that despite its obvious attributes “Black Box” trading was very tricky. The algorithms may work for a while [even a very long while] and then, inexplicably, they’ll just completely “BLOW-UP”. To him the most important component to quantitative trading was not the creation of a good model. To him, amazingly, that was a challenge but not especially difficult. The real challenge, for him, was to “sniff out” the degrading model prior to its inevitable “BLOW-UP”.

And I quote his humble, resolute observation:

“because, you know, eventually they ALL blow-up“

… as most did in August 2007.

It was a “who’s who” of legendary hedge fund firms that had assembled “crack” teams of “Black Box” modelers: Citadel, Renaissance, DE Shaw, Tudor, Atticus, Harbinger and so many Tiger “cubs” including Tontine [not all strictly quantitative but, at least, dedicated to the intellectual dogma] … all preceded by Amaranth in 2006 and the legendary Long Term Capital Management’s [“picking up pennies in front of a steam-roller“] demise one decade earlier.

Years of monthly returns with exceedingly low volatility were turned “inside out” in just 4-6 weeks as many funds suffered monthly losses > 20% which was previously considered highly improbable and almost technically impossible … and, voilà … effectively, a sword was violently thrust through the heart of EVERY “Black Box” model. VaR and every other risk management tool fell victim to legitimate liquidity issues, margin calls and sheer human panic.

Many of these firms somehow survived but only by heavily gating their, previously lightly-gated, quarterly liquidity provisions. Basically, as an investor, you could not “get out” if you wanted to. These funds changed the liquidity rules to suit their own needs … to survive … though many did fail.

Anyway … to follow up on my dialogue with the esteemed portfolio manager … I asked “why do they all “BLOW-UP”? What are those common traits that seem to effect just about every quantitative model despite the intellectual and capital fire-power behind them? And if they all eventually “BLOW-UP” then why are we even doing this?”

He answered the second part of the question first … and I paraphrase …

“We are all doing this because we can all make a lot of money BEFORE they “BLOW-UP”. And after they do “BLOW-UP” nobody can take the money back from us.” He then informed me why all these models actually “BLOW-UP”. “Because despite what we all want to believe about our own intellectual unique-ness, at its core, we are all doing the same thing. And when that occurs a lot of trades get too crowded … and when we all want to liquidate [these similar trades] at the same time … that’s when it gets very ugly.“.

I was so naive. He was so right.

Exactly What Were We All Doing?

We all knew what the leaders wanted and, of course, we wanted to please them. Essentially they wanted to see a model able to generate 4-6% annual returns [seems low, I know, but I’ll address that later] … with exceptionally low volatility, slim draw-down profiles and winning months outweighing the losing months by about 2:1. They also wanted to see a model trading exceptionally liquid securities [usually equities].

Plus the model, itself, had to be completely scientific with programmable filtering and execution [initiation and liquidation] features so that it could be efficiently applied and, more importantly, stringently back-tested and stress-tested . Long or short did not really matter. Just make money within the parameters. Plus, the model had to be able to accommodate at least $100M [fully invested most of the time as cash was not an option] and, hopefully, much more capital. This is much easier said than done but, given the brainpower and financial resources, was certainly achievable.

This is what all the “brainpower” learned … eventually.

First of all, a large number of variables in the stock selection filter meaningfully narrowed the opportunity set … meaning, usually, not enough tickers were regularly generated [through the filter] to absorb enough capital to tilt the performance meter at most large hedge funds…as position size was very limited [1-2% maximum]. The leaders wanted the model to be the hero not just a handful of stocks. So the variables had to be reduced and optimized. Seemingly redundant indicators [for the filter] were re-tested and “tossed” and, as expected, the reduced variables increased the population set of tickers … but it also ramped the incremental volatility … which was considered very bad. In order to re-dampen the volatility capital limits on portfolio slant and sector concentration, were initiated. Sometimes market neutral but usually never more than net 30% exposure in one direction and most sectors could never comprise more than 5% of the entire portfolio. We used to joke that these portfolios were so neutered that it might be impossible for them to actually generate any meaningfully positive returns. At the time of “production” they actually did seem, at least as a model, “UN-BLOW-UP-ABLE” considering all the capital controls, counter correlations and redundancies.

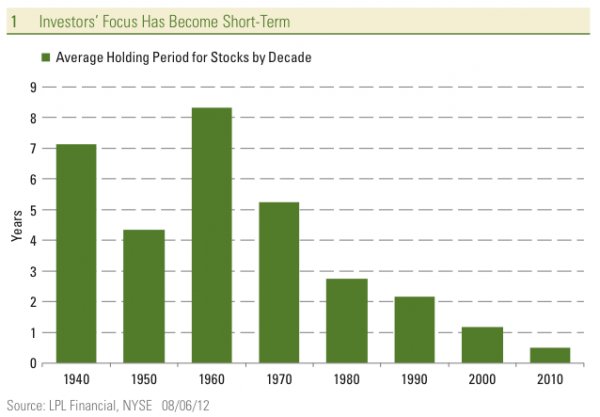

Another common trait of these models that was that, in order to minimize volatility, the holding periods had to be much shorter than a lot of us had anticipated. So execution [both initiation and liquidation] became a critical factor. Back then a 2-3 day holding period was considered acceptable, but brief, although there were plenty of intra-day strategies … just not at my firm … at least not yet. With these seemingly high velocity trading models [at the time], price slippage and execution costs, became supreme enemies of forecasted returns. To this day the toughest element to back-testing is accessing tick data and accurately pinpointing execution prices. Given this unpredictability, liberal price slippage was built into every model … and the model’s returns continued to compress … not to mention the computer time charges assessed by the leadership [which always pissed me off].

So, given all of this, what types of annual returns could these portfolios actually generate? A very good model would generate a net 5-7% … but 3.5-5% was acceptable too. So how then could anybody make any real money especially after considering the labor costs to construct/manage/monitor these models … which … BTW … was substantial?

Of course there was only one real way … although it would incrementally cut into performance even more, in the near term, but ultimately pay off if the “live” model performed as tested. The answer = LEVERAGE … and I mean a lot of it … as long as the volatility was low enough.

Back-tested volatility was one thing and live model volatility was another thing so leverage was only, ever so slowly, applied … but as time passed and the model performed, the leverage applied would definitely increase. Before you knew it those 5% returns were suddenly 20-25% returns as the positive beauty of leverage [in this case 4-5x] was unleashed.

Fast forward 10 years and the objectives of hedge funds are still the same. Generate positive absolute returns with low volatility … seeking the asymmetrical trade … sometimes discretionary but in many cases these “Black Box” models still proliferate. And BTW … they are all “doing the same thing“ as always … current iteration = levered “long” funds.

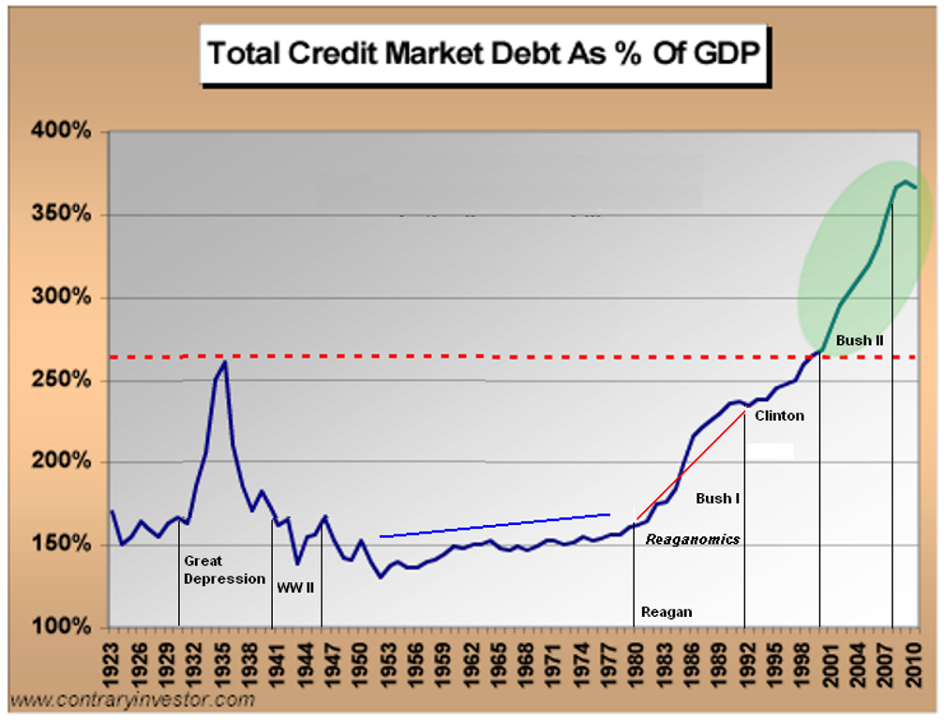

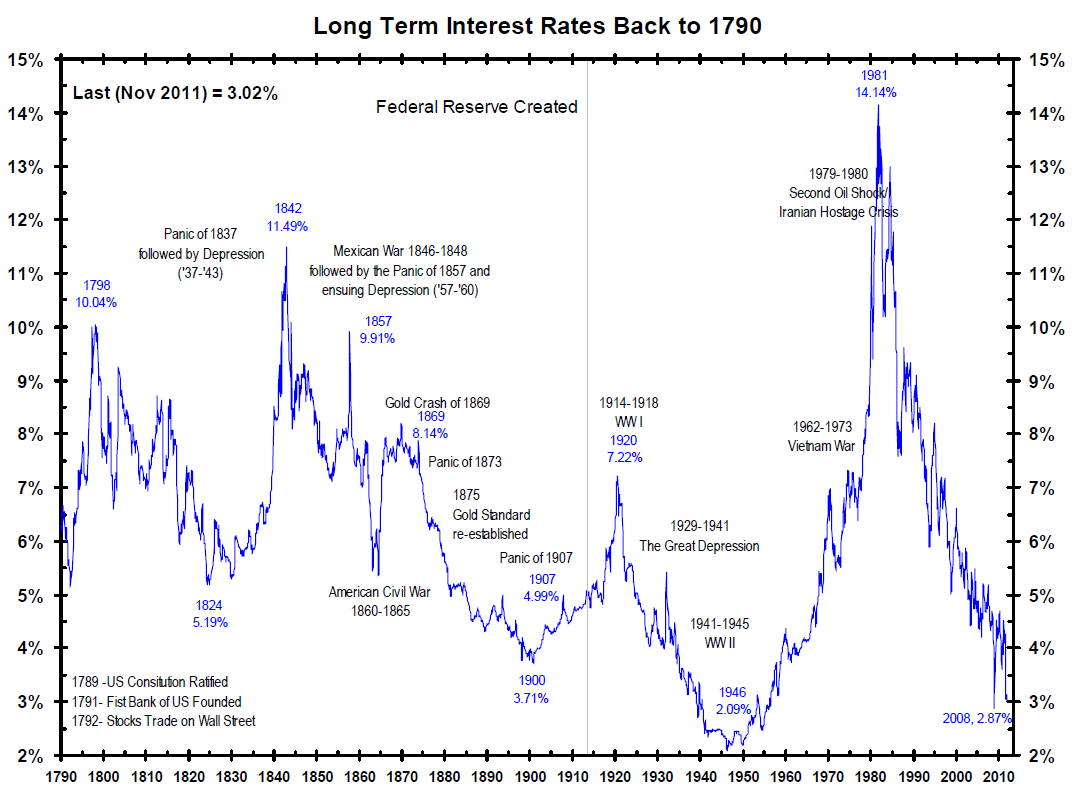

What has changed though is the increased dollars managed by these funds [now > $3.5T] and the concentration, of these dollars, at the twenty largest funds [top heavy for sure]. What has also considerably changed is the cost of money … aka leverage. It is just so much cheaper … and, of course, is still being liberally applied but, to reiterate, in fewer hands.

Are these “hands” any steadier than they were ten years ago? I suppose that is debate-able but my bet is that they are not. They are still relying on regression-ed and stress tested data from the past [albeit with faster computers & more data]. They may even argue that their models are stronger due to the high volatility markets of ’08/’09 that they were able to survive and subsequently measure, test and integrate into their current “Black Boxes” … further strengthening their convictions … which is the most dangerous aspect of all.

Because …

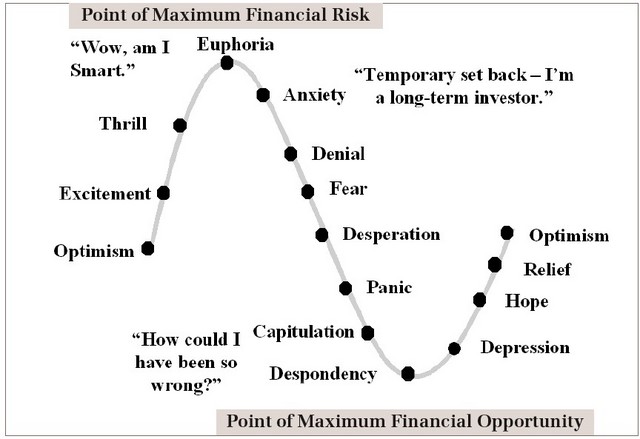

- Strong Conviction … aka Over Confidence +

- Low Volatility +

- High Levels/Low Costs of Leverage [irrespective of Dodd-Frank] +

- More Absolute Capital at Risk +

- Increased Concentration of “At Risk” Capital +

- “Doing the Same Thing”

… Adds up to a Combustible Market Cocktail.

Still a catalyst is needed and, as always, the initial catalyst is liquidity [which typically results in a breakdown of historic correlations as the models begin to “knee-bend” … and the perceived safety of hedges is cast in doubt] followed by margin calls [the ugly side of leverage … not to mention a whole recent slew of ETF’s that are plainly levered to begin with that, with the use of borrowed money, morph into “super-levered” financial instruments] and concluding with the ever ugly human panic element [in this case the complete disregard for the “black box” models even after doubling/trebling capital applied on the way down because the “black box” instructed you to]. When the “box” eventually gets “kicked to the curb” … that is when the selling ends … but not after some REAL financial pain.

So can, and will, this really occur once again? It can absolutely occur but it is just impossible to know exactly when … although there are plenty of warning signs suggesting its likelihood … as there have been for some time.

However, I am quite confident of the following:

- The Fed Is Clueless On All Of This

[just too many moving parts for them … they cannot even coordinate a simple “cover-up” of leaked monetary policy … so no way the academics can grasp any of this … just liked they missed LTCM. Nor it seems…do they have any interest in it as it is too tactical for a strategically inclined central banker]. - “Eventually They ALL Blow-Up”

- The Only Real Question Left To Answer =

HOW BIG CAN THIS POSSIBLE “BLOW-UP” ACTUALLY BE? I think … if the pieces simultaneously shudder … then pretty BIG