Economics in One Lesson

I highly recommend reading the book and/or view the video series on each lesson. It is common-sense economics. Many don’t see the secondary effects (a needed skill for investing!) of particular actions. Say you see a government building a bridge across a river–fantastic, you say because we need infrastructure. But what could individuals have done with their money instead? What products or services were foregone to build that bridge? I bet not 1 in 100,000 thinks of that. YOU will.

The Book: economics_in_one_lesson_hazlitt RECOMMENDED!

Video Series of Economic in One Lesson: http://archive.mises.org/14406/economics-in-one-lesson-the-video-series/

I will pay someone to find a better introductory book on basic, common-sense economics.

Economic Primers:

Intro to Austrian Economics by Taylor

lessons_for_the_young_economist_murphy

Essentials of Economics by Faustino Ballve

A more advanced exposition:Foundations of the Market Price System

If you don’t grasp economic principles (especially micro-economics) then investing successfully will be a Herculean task.

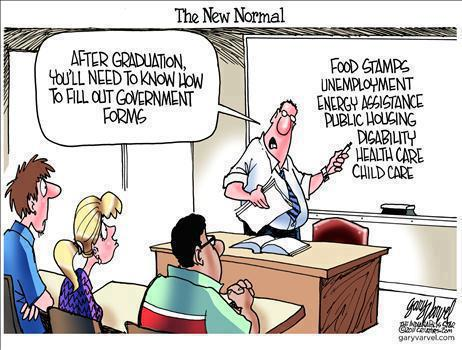

More jobs or wealth?

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/31/business/majority-of-new-jobs-pay-low-wages-study-finds.html?_r=2&hp

August 30, 2012

While a majority of jobs lost during the downturn were in the middle range of wages, a majority of those added during the recovery have been low paying, according to a new report from the National Employment Law Project.

The disappearance of mid-wage, mid-skill jobs is part of a longer-term trend that some refer to as a hollowing out of the work force, though it has probably been accelerated by government layoffs.

“The overarching message here is we don’t just have a jobs deficit; we have a ‘good jobs’ deficit,” said Annette Bernhardt, the report’s author and a policy co-director at the National Employment Law Project, a liberal research and advocacy group.

The report looked at 366 occupations tracked by the Labor Department and clumped them into three equal groups by wage, with each representing a third of American employment in 2008. The middle third — occupations in fields like construction, manufacturing and information, with median hourly wages of $13.84 to $21.13 — accounted for 60 percent of job losses from the beginning of 2008 to early 2010.

The job market has turned around since then, but those fields have represented only 22 percent of total job growth. Higher-wage occupations — those with a median wage of $21.14 to $54.55 — represented 19 percent of job losses when employment was falling, and 20 percent of job gains when employment began growing again.

Lower-wage occupations, with median hourly wages of $7.69 to $13.83, accounted for 21 percent of job losses during the retraction. Since employment started expanding, they have accounted for 58 percent of all job growth.

The occupations with the fastest growth were retail sales (at a median wage of $10.97 an hour) and food preparation workers ($9.04 an hour). Each category has grown by more than 300,000 workers since June 2009.

Some of these new, lower-paying jobs are being taken by people just entering the labor force, like recent high school and college graduates. Many, though, are being filled by older workers who lost more lucrative jobs in the recession and were forced to take something to scrape by.

“I think I’ve been very resilient and resistant and optimistic, up until very recently,” said Ellen Pinney, 56, who was dismissed from a $75,000-a-year job in which she managed procurement and supply for an electronics company in March 2008.

Since then, she has cobbled together a series of temporary jobs in retail and home health care and worked as a part-time receptionist for a beauty salon. She is now working as an unpaid intern for a construction company, putting together bids and business plans for green energy projects, and has moved in with her 86-year-old father in Forked River, N.J.

“I really can’t bear it anymore,” she said, noting that her applications to places like PetSmart and Target had gone unanswered. “From every standpoint — my independence, my sense of purposefulness, my self-esteem, my life planning — this is just not what I was planning.”

As Ms. Pinney’s experience shows, low-wage jobs have not been growing especially quickly in this recovery; they account for such a big share of job growth mostly because mid-wage job growth has been so slow.

Over the last few decades, the number of mid-wage, mid-skill jobs has stagnated or declined as employers chose to automate routine tasks or to move them offshore.

Job growth has been concentrated in positions that tend to fall into two categories: manual work that must be done in person, like styling hair or serving food, which usually pays relatively little; and more creative, design-oriented work like engineering or surgery, which often pays quite well.

Since 2001, employment has grown 8.7 percent in lower-wage occupations and 6.6 percent in high-wage ones. Over that period, mid wage occupation employment has fallen by 7.3 percent.

This “polarization” of skills and wages has been documented meticulously by David H. Autor, an economics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A recent study found that this polarization accelerated in the last three recessions, particularly the last one, as financial pressures forced companies to reorganize more quickly.

“This is not just a nice, smooth process,” said Henry E. Siu, an economics professor at the University of British Columbia, who helped write the recent study about polarization and the business cycle. “A lot of these jobs were suddenly wiped out during recession and are not coming back.”

On top of private sector revamps, state and local governments have been shedding workers in recent years. Those jobs lost in the public sector have been primarily in mid and higher-wage positions, according to Ms. Bernhardt’s analysis.

“Whenever you look at data like these, there is this tendency to get overwhelmed, that there are these inevitable, big macro forces causing this polarization and we can’t do anything about them. In fact, we can,” Ms. Bernhardt said. She called for more funds for states to stem losses in the public sector and federal infrastructure projects to employ idled construction workers. Both proposals have faced resistance from Republicans in Congress. (Editor: More public work means more taxes; more taxes equal less production; and less production equals less wealth).

Dwight R. Lee

Creating Jobs vs. Creating Wealth

Remember the opportunity costs.

January 2000 • Volume: 50 • Issue: 1 • 20 comments

Government policies are commonly evaluated in terms of how many jobs they create. Restricting imports is seen as a way to protect and create domestic jobs. Tax preferences and loopholes are commonly justified as ways of increasing employment in the favored activity. Presidents point with pride to the number of jobs created in the economy during their administrations. Supposedly the more jobs created the more successful the administration. There probably has never been a government spending program whose advocates failed to mention that it creates jobs. Even wars are seen as coming with the silver lining of job creation.

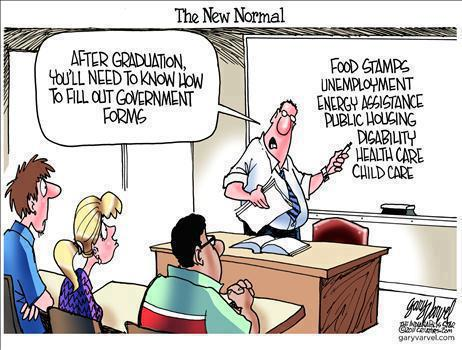

Now there is nothing wrong with job creation. Working in jobs is an important way people create wealth. So the emphasis on job creation is an understandable one. But it is easy for people to forget that creating more wealth is what we really want to accomplish, and jobs are merely a means to that end. (How about having people paid for building sand castles during low tides—infinite work?) When that elementary fact is forgotten, people are easily duped by arguments that elevate creation of jobs to an end in itself. While these arguments may sound plausible, they are used to support policies that destroy wealth rather than create it. I shall consider a few of the depressingly many examples in this column and the next.

Creating Jobs Is Not the Problem

The purpose of all economic activity is to produce as much value as possible with the scarce resources (including human effort) available. But no matter how far we push back the limits of scarcity, those limits are never vanquished. Scarcity will forever prevent us from securing all the things we desire. There will always be jobs to do far more than can ever be done. So creating jobs is not the problem. The problem is creating jobs in which people produce the most value. This is the point of the apocryphal story of an engineer who, while visiting China, came across a large crew of men building a dam with picks and shovels. When the engineer pointed out to the supervisor that the job could be completed in a few days, rather than many months, if the men were given motorized earthmoving equipment, the supervisor said that such equipment would destroy many jobs. “Oh,” the engineer responded, “I thought you were interested in building a dam. If it’s more jobs you want, why don’t you have your men use spoons instead of shovels.”

As I tell my students at the University of Georgia, I will employ every person in our college town of Athens if they’ll only work for me cheaply enough, say a nickel a month. Lower the wage a bit more and I’ll hire everyone in the entire state of Georgia. If I hired workers at those wages, I could make a profit having them build dams with spoons. Of course, the students recognize that my offer is silly since they can make far more working for other employers, which reflects the more important reason my offer is silly: concentrating on the number of jobs ignores the value being created, or not created. More value will be produced in the higher-paying jobs my students can get than in the ones I am offering. A big advantage realized from the wages that emerge in open labor markets is that they attract people into not just any employment, but into their highest-valued employment.

Another advantage of market wages is that they force employers to consider the opportunity cost of hiring workers their value in alternative jobs and to remain constantly alert for ways to eliminate jobs by creating the same value with fewer workers. All economic progress results from being able to provide the same, or improved, goods and services with fewer workers, thus eliminating some jobs and freeing up labor to increase production in new, more productive jobs. The failure to understand this source of increasing prosperity explains the widespread sympathy with destructive public policies.

Dynamiting Our Way to More Jobs

In the 1840s a French politician seriously advocated blowing up the tracks at Bordeaux on the railroad from Paris to Spain to create more jobs in Bordeaux. Freight would have to be moved from one train to another and passengers would require hotels, all of which would mean more jobs. (This proposal was discussed and demolished by the nineteenth-century economist and essayist Frederic Bastiat in Economic Sophisms, pp. 94-95, available from FEE.)

This proposal is even more absurd than my offer to hire people for a nickel a month. At least I would employ workers to produce something of value, rather than to partially undo damage that is inflicted needlessly. Unfortunately, absurdity does not prevent economically destructive policies from being proposed and implemented. Using the jobs-creation justification, politicians commonly enact legislation that increases the effort required to produce a given amount of value.

One of the arguments for restricting imports is that it will create (or protect) domestic jobs. True, it will create some domestic jobs, just as destroying a section of a rail line will create domestic jobs. But also like a break in a rail line, import restrictions make it more costly to obtain valuable products. The only reason a country imports products is that it is the cheapest way to acquire them; it takes fewer workers to obtain the imported products through foreign trade than by producing them directly. In this way trade is like a technological advance, freeing up workers and allowing them to increase the production of goods and services available for consumption. Import restrictions create jobs in the same way dynamiting our railroads, bombing our factories, and requiring that workers use shovels instead of modern earth-moving equipment would create jobs. Always keep in mind that creating jobs is a means to the ultimate end of economic activity, which is creating wealth.

Creating Government Jobs

Because people tend to think of jobs as ends rather than means, they are easily fooled into supporting government programs on grounds that jobs will be created. We have all heard people argue in favor of military bases, highway construction, and environmental regulations on business on these grounds. To justify spending, government agencies commonly perform benefit/cost studies in which the jobs created are counted as benefits. This is like counting the hours you work to earn enough money to buy a car as one of the car’s benefits. The jobs created by a government project represent a cost of the project: the opportunity cost. The workers employed in government activities could be producing value doing something else. The relevant question is not whether a government project creates jobs, but whether the workers in those jobs will create more wealth than they would in other jobs. This is a question advocates of government programs don’t want asked. If it were, there would be far fewer low-productivity government jobs and far more high-productivity private-sector jobs.