Today we had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Chris Leithner. He has lived in Australia for the last twenty years and is the author of The Evil Princes of Martin Place. The book delineates the evils of all central banks and has some unique perspectives on Australia’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

We took this opportunity to ask Chris about his thoughts on central banking, investing and his views on the RBA, the Australian dollar and Australian stocks.

The Dollar Vigilante (TDV): Thanks for taking the time to speak with us, Chris. To begin, give us some background on yourself.

Chris LeithnerChris Leithner (CL): Sure, I came to Australia from Canada in 1987, in order to take a postgraduate degree. After a few years of further study in the UK, I returned to Oz in 1991. After a couple of years, I became a jaded academic; and after a few more I became an ex-academic. I learnt that the adage “those who can, do; and those who can’t, teach” has more than a ring of truth to it. Partly for that reason, and also because in the 1990s I also discovered Austrian School economics, Ben Graham and their commonalities, in 1999 I formed Leithner & Company (http://www.leithner.com.au). It’s a private investment company, based in Brisbane, which adheres strictly to the “value” approach to investment pioneered by Graham and to the economic insights of Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard.

Chris LeithnerChris Leithner (CL): Sure, I came to Australia from Canada in 1987, in order to take a postgraduate degree. After a few years of further study in the UK, I returned to Oz in 1991. After a couple of years, I became a jaded academic; and after a few more I became an ex-academic. I learnt that the adage “those who can, do; and those who can’t, teach” has more than a ring of truth to it. Partly for that reason, and also because in the 1990s I also discovered Austrian School economics, Ben Graham and their commonalities, in 1999 I formed Leithner & Company (http://www.leithner.com.au). It’s a private investment company, based in Brisbane, which adheres strictly to the “value” approach to investment pioneered by Graham and to the economic insights of Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard.

TDV: How did you first get exposed to Austrian economics?

CL: Increasingly repelled by the absurdities and outright falsehoods of the economic and financial mainstream, I found Austrian Economics in exactly the way that the Austrian School shows how so many things happen: by accident rather than by design. I found it almost everywhere except at university; and as I think back, the more of it that I found, the more repugnant academic life became. I read Mises, Rothbard and others on capital, value, interest rates and the business cycle. I also read Lionel Robbins, The Great Depression (1934) and Wilhelm Röpke, Crises and Cycles (1936). Although Robbins later disavowed Austrian methods and insights, I realised that both he and Röpke provided clear and forceful expositions of the mechanics of the Austrian interest-rate and business-cycle model. Amazingly, within a couple of years of the Great Depression’s nadir, they published more theoretically and empirically rigorous accounts than (for example) Ben Bernanke’s Essays on the Great Depression, Princeton University Press, 2004.

Not only has the mainstream learnt nothing since the 1930s: it has unlearnt what’s worth knowing!

TDV: Yes, it’s not what they don’t know but it is what they know that just ain’t so. So, why did you write The Evil Princes of Martin Place?

CL: I sought to demonstrate to an audience of interested laypeople, both in Australia and other countries, that there’s little new under the sun: the “Global Financial Crisis,” as the events of 2007-2009 are commonly known in Australia, is merely the latest in a long series of economic and financial crises that have punctuated the history of the past 250 or so years. Like its predecessors, three of which (namely the Panic of 1907, the Depression of 1920-1921 and the Great Depression of 1929-1946) the book analyses in detail, interventionist policies – in particular, legal tender laws, fractional reserve banking and central banking – are the GFC’s ultimate causes. Accordingly, only when we recognise that monetary central planning is the ultimate source of our financial and economic distemper, and when it either collapses or is consigned to the dustbin of history, and when 100%-reserve banking and sound money replace fractional reserve and central banking and fiat currency, will the ruinous cycle of boom and bust become as thing of the past.

TDV: Tell our audience generally what the book is about

CL: Sure, Part I (Chapters 1-5) uses basic logic and evidence to isolate the causes of the GFC, Panic of 1907, etc. It demonstrates, in short, that these crises are failures of government – and not of liberty. Following Herta de Soto, it demonstrates that deposits are not (and can never legitimately be) loans, that the history of fractional reserve banking is the history of bank crises and failures. Following Rothbard and Mises, it also shows how fractional reserve banks misappropriate and counterfeit.

Part II (Chaps. 6-9) analyses counterfeit money, the central bank and the welfare-warfare state. It demonstrates, following a long line of scholars, that fractional reserve banking is logically absurd, utterly fraudulent – and hence legally untenable. It also outlines the basic operations of central banking (e.g., open market operations, etc.). Conceiving the central bank as a monetary central planner, it also demonstrates (following Mises, who did it did for central planning generally) that monetary central planning inevitably fails. Finally, following Hoppe, who demonstrated in Democracy: The God That Failed (Transaction Books, 2002) that private property (i.e., individual ownership and rule) and democracy (i.e., collective ownership and majority rule) are incompatible, it outlines the invidious moral and ethical consequences (which it calls the “monetary roots of democratic pathologies”) of fractional reserve and central banking.

Part III (Chaps. 10-14) provides historical analyses of where we’ve been, where we are now and where we’re headed. It puts the Depression of 1920-21 and Great Depression into an Austrian context; so too with Australia’s “miracle economy” of 1991-2007 and the Commonwealth Government’s reaction to the GFC. It concludes that its reaction has merely set the stage for a later and bigger crisis.

Finally, Part IV (chaps 15-16) outlines where we should go – namely outlaw fractional reserve and central banking – and provides further reading for those who are interested.

TDV: We find all of your subject matter interesting but the main reason I wanted to interview you was to give the TDV audience some perspectives on what is going on in Australia right now. Tell us some of your thoughts about Australia’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia.

CL: Australians have become a bit cocky in recent years, to the point where “Australian Exceptionalism” or something akin to it swells many hearts; it’s not just The Lucky Country: to many people, it’s apparently The Country That Deserves to Be Lucky.

TDV: The same thing has been happening in Canada. It’s amazing what living in a place with some natural resources in the ground and a currency performing relatively well can do to puff out the chests of some people!

CL: Haha, yes. One of my intentions in The Evil Princes of Martin Place is to remind them that the laws of economics are universal across time and space – and therefore, that, just as fractional reserve and central banking inflated the booms that have burst in Europe and the U.S., so too they’ve inflated the booms that will bust in China and Australia.

TDV: Explain to us how the RBA is different, or similar, from the other central banks we are more familiar with like the Fed, BoE and BoJ

CL: For all practical purposes, it seems to me that central banks’ similarities (which The Evil Princes emphasises) are far more important than their differences. As an analogy, the Fierce Snake (Oxyuranus microlepidotus), Common Brown Snake (Pseudechis australis) and Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) are the world’s three most-venomous snakes. For all I know (I don’t), their diets, reproductive habits and habitats, among other things, differ. But what’s most relevant from my point of view is that each is very poisonous – and is an Australian native. Similarly, a mainstream economist might assert that over the past decade the RBA has targeted the CPI more formally than the Fed. Both, however, relentlessly undertake the open market ops that ignite the boom that eventually busts, and it’s that commonality that I try to keep uppermost in mind.

TDV: The Australian Dollar (AUD) has been on a wild ride the last few years… how do you explain this from your Austrian viewpoint and from what you know about the AUS central bank?

CL: Because Leithner & Co. invests almost exclusively in Australia and New Zealand, I’ve never thought about it. Well, that’s not quite true: the $A is a fiat currency; and as such, its purchasing power almost constantly falls. But I have no insight whether it will melt faster than the £, €, $US, etc. I suspect, but obviously don’t know, that taking short-term or even medium-term positions on the price of the $A vis-à-vis another currency is either a waste of time or a rod for one’s own back. Certainly I don’t know anybody who’s made a living – let along accumulated significant wealth – trading the $A or any other currency.

Your question prompts me to reflect that, when it comes to the currency, I am very Grahamite; that is, I concentrate on the micro (the security) rather than the macro. Your question also brings to mind Buffet’s observation in 1994: “If Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan were to whisper to me what his monetary policy was going to be over the next two years, it wouldn’t change one thing I do.” In effect, in 2009 Glenn Stevens, Ben Bernanke and all the sordid rest DID shout what their monetary policies were going to be, and it hasn’t changed either my approach to investment or my highly jaundiced attitude towards central bankers and central banking.

TDV: Give us an overview of the current political/central banking climate in AUS… what’s your thoughts? Should we be buying AUS stocks? AUD? Or selling?

CL: Well, let’s first take the mainstream’s prevailing attitude towards central banking in general and the RBA in particular: central planning rules! Not just in Oz, but in all Western countries (and Eastern ones, for all I know) the state has embedded its protections of fractional reserve and central banks so deeply within its legislation and regulations – in other words, it has extended such enormous privileges to these banks for such a long time – that virtually nobody now recognises bankers for what they have long been: massively featherbedded white-collar wharfies (for decades until a decade or so ago, longshoremen were the most notoriously protected, overpaid and arrogant workers in Australia). The events of the past couple of years have alerted the man in the street to the reality that something is rotten in Denmark — or, more precisely, Australian and other banks — but he can’t quite put his finger on it.

In Australia, economists, investors and journalists babble endlessly about the level at which the Reserve Bank should “set” the “official interest rate” (by which they mean the Overnight Cash Rate). Alas, almost nobody bothers to ask why it should be set, or whether it actually can be fixed. After all, the benchmark price of (say) wheat isn’t set: it’s discovered throughout the day at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Similarly, the spot price of copper is constantly discovered and rediscovered at the London Metals Exchange. More generally, the impersonal forces of supply and demand determine many prices. Yet, for reasons rarely discussed and never justified, virtually nobody baulks at the notion that a short-term money market rate of interest must be “set” by a committee of price-fixers and central planners in Martin Place, Sydney.

Hence, an inconvenient question: given that most “right thinking” people like mainstream economists and financiers (correctly) believe that the production of goods such as motor cars, frozen vegetables, etc., should occur within a régime of market competition, why do the Good and the Great insist – some of them quite vehemently – that “we” must exclude the production of money from market forces? Why, in an allegedly free society, must the government monopolise the definition of money? Why must its production and regulation be entrusted to a deified government monopolist called the central bank? Nobody in mainstream Australia is ever able to answer these questions; instead, they ridicule or simply ignore them.

Yet even to consider these questions is to grasp that the Global Financial Crisis is not a “market failure.” Rather – and in a way that parallels the collapse of Communist economies – the GFC is the inevitable consequence of the hubris of central planning. Communism epitomised general economic central planning, and it eventually collapsed. Central banking, whether in Australia, Britain, China or the U.S., is monetary central planning; as a result, it too will ultimately be consigned to the dustbin of history. From the repudiation of the gold clause and confiscation of gold in 1933 to the closing of the “gold window” in 1971, the chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, as well as his counterparts in the Reserve Bank of Australia, etc., have increasingly deprived market participants of market signals – that is, of real information in the form of unfettered rates of interest. In particular, market participants have been deprived of a key warning signal and great source of discipline (the right to exchange dollars for gold). Central bankers, in short, have caused credit markets to emit false signals; as a result, these markets don’t tell the truth about time.

TDV: We totally agree, of course. And also find it so bizarre that hardly anyone questions having communist style central planning embedded at the very heart of the so-called capitalist system. What is your take on Australian stocks?

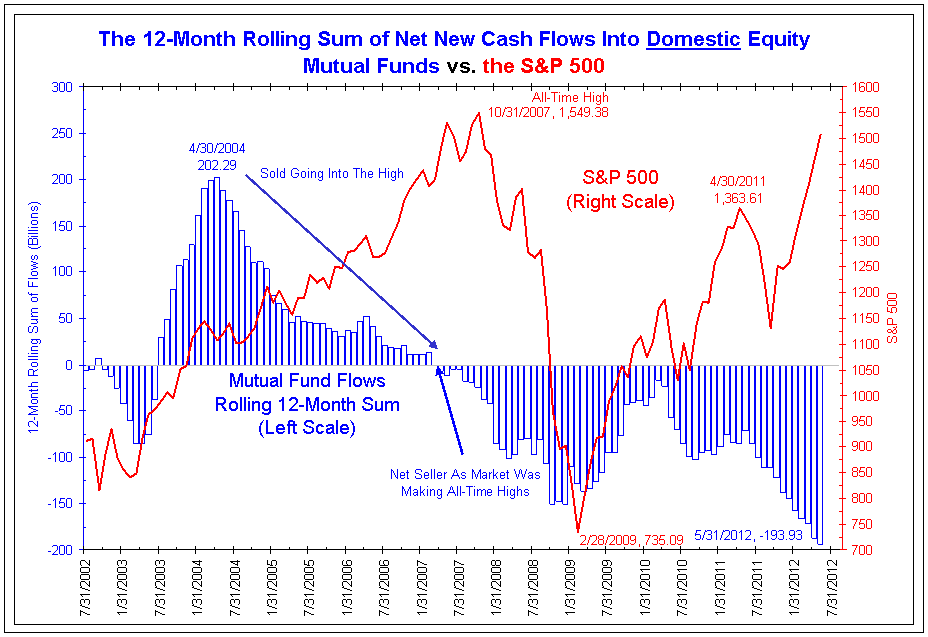

CL: In Leithner & Co.’s current Newsletter to its shareholders, I note a paradox: those who didn’t see the GFC coming (and remained wilfully blind after it erupted) – the very people who incurred big losses in 2007-2009, which they’ve not recouped – today remain resolutely upbeat about the future. They were diametrically wrong then; why should anybody think they’re less wrong today?

In sharp contrast, the doughty few who anticipated trouble and who have consistently generated profits since 2007 remain downcast today. It’s demonstrably false to assert, as the mainstream has since 2007, that “nobody saw it coming.” What’s certainly true is that the few who foresaw the GFC and now see that we’re merely in the eye of the storm, were then and today remain, from a mainstream point of view, “nobodies.”

A second point is that in a Newsletter dated 26 June 2009, I posited assumptions and conducted an analysis that yielded nine estimates of the All Ordinaries Index’s “fair value.” If earnings fall to their long-term trend and bearish multiple emerges, then the All Ords’ fair value is 1,688 – roughly half the level of its low in March 2009 and one-third of its level (4,700) in early July 2011. If earnings remain constant and the “bullish” multiple suddenly prevails, then fair value is 5,512 – a modest 67% above the March 2009 trough. Mid-range assumptions with respect to both earnings and the multiple generate an estimate of 3,127 – just below the March low. Re-reading that analysis and considering its premises, I think its conclusions remain sound: Australian investors need to incorporate into their plans the possibility that Australian indexes fall by 50% or more.

A third point is that, recent decades in Australia, have not, in economic and financial terms – and as the Commonwealth Government, RBA and their sock-puppets in the media and universities strenuously insist – been truly stable. In The Evil Princes I noted that for seven decades Communism in the Soviet Union was apparently secure. But it was hardly durable, as its sudden and unexpected (to the Western mainstream) collapse demonstrated. I also show that since the early 1990s the much-vaunted “fundamentals” of the Australian economy have hardly – despite the mainstream’s ubiquitous and often strident insistence – been sound. Since 2007, it’s become obvious in Europe and the U.S. that the “stability” of the past few decades was – like the “strength” of the Soviet Union – apparent rather than real. The truth is that the long Australian boom since the early 1990s has not reflected the success of the mainstream’s interventionist policies. The ructions since 2007, however, have revealed the artificiality of the conditions these interventions created.

Alas, like the Bourbons of old, today’s politicians, central and fractional reserve bankers have forgotten nothing and learnt nothing from the financial and economic catastrophes they’ve repeatedly fomented – and thereby expose the rest of us to the next crisis. Unfortunately, the lesson of history seems to be that the politicians people admire most extravagantly are (like Franklin Roosevelt) the most audacious liars; conversely, the ones they erase from memory are, like Warren Harding, those who dare to tell them the truth.

Accordingly, since 2007 governments around the world have intervened massively and lied flagrantly. Their frenzied “fiscal stimulus” and hysterical “monetary stimulus” have ignored the lessons of the “Good Depression” of 1920-1921 and reprised many of the errors committed during the Great Depression of 1929-1946. Most notably, major central banks are presently moving heaven and earth to suppress market rates of interest; the appropriate course is to abandon the intervention and to let rates rise. Similarly, Western governments are increasing expenditure and incurring huge deficits; the correct policy, of course, is to slash spending, taxes and deficits, and to use the resultant surplus to retire debt. Since 2007, in short, central bankers and politicians – as much in Oz as in Europe, China and America – have been energetically inflating the next bubble and thereby stimulating the next crisis. My prognosis is therefore sombre.

TDV: We agree with you on that count as well. You certainly, more than 99.9% of money managers out there, really know what is going on thanks to your grasp of Austrian economics. For those interested, please let them know about how they can take advantage of your investment services.

CL: A short summary of our results since inception can be seen here, and an extended analysis of our results during the past decade and its strategy for the next ten years can be seen here.

Leithner & Co. accepts new investors. It caters primarily to professional and sophisticated investors as defined in sections 708(8) and 708(11) of the Australian Corporations Act. In plain English, that means investments of at least $A500,000. Also, because Leithner & Co. is a company and not a fund, its investors own shares in a private company rather than units in a unit trust (or what Americans would call a mutual fund). Unlike units, these shares are illiquid. So not just as a result of its investment philosophy, but also as a consequence of its structure, Leithner & Co. probably isn’t suitable for most people.

Learn more:http://www.leithner.com.au/archives.htm

Other Austrian Value Investors

Bestinver

Another Investor who combines his value investing philosophy with Austrian economics: http://www.bestinver.com/prensa.aspx?orden=estudios

James Grant

Note what Jim Grant says in the video interview, “The value that you see is the result of manipulated interest rates? We are in a BUBBLE of perceived “SAFE” Haven assets (think 30 years bonds at sub-2.5% or two year bonds at 0.003%)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mr-JHFmYT3o&feature=player_embedded

Chris LeithnerChris Leithner (CL): Sure, I came to Australia from Canada in 1987, in order to take a postgraduate degree. After a few years of further study in the UK, I returned to Oz in 1991. After a couple of years, I became a jaded academic; and after a few more I became an ex-academic. I learnt that the adage “

Chris LeithnerChris Leithner (CL): Sure, I came to Australia from Canada in 1987, in order to take a postgraduate degree. After a few years of further study in the UK, I returned to Oz in 1991. After a couple of years, I became a jaded academic; and after a few more I became an ex-academic. I learnt that the adage “