How Best to Learn?

An intelligent reader and I have had an exchange on how to approach using the resources on this blog to learn most efficiently. There are many resources on this blog and in the Value Valut–just email me at aldridge56@aol.com to request a key)–but the orgainization can be improved upon.

Ben Graham was right when he said a conservative investor can do better than average through using a disciplined, rational approach here: http://www.grahaminvestor.com/

Benjamin Graham always tried to buy stocks that were trading at a discount to their Net Current Asset Value. In other words he buy stocks that were undervalued and hold them until they became fully valued.

“The determining trait of the enterprising investor is his willingness to devote time and care to the selection of securities that are both sound and more attractive than the average. Over many decades, an enterprising investor of this sort could expect a worthwhile reward for his extra skill and effort in the form of a better average return than that realized by the passive investor.” Ben Graham in “The Intelligent Investor”, 1949.

The problem is how difficult it is to perform much better than average. You have to expand your skills and circle of competence while keeping the costs of your learning to a minimum.

I will be traveling the next few day (until Tuesday), but I will think carefully on my answer to his question. Other readers, please feel free to offer your experiences, thoughts and suggestions. The quality of readership here is outstanding.

Dialogue

Hi John,

Just a quick question regarding your suggested learning methodology.

I am currently working through your lectures (blog and Value Vault) and there are a number of useful book recommendations. Would you suggest reading the books before moving on, to appreciate and understand the subsequent lectures? e.g. In lecture two, you quote, “The professor (Joel Greenblatt in his Special Situations Investing Class at Columbia GBS) stressed studying carefully the essays of Warren Buffett.”

I do have the book and was wondering whether to take a break from the lectures and study the book, then return to the lectures. Given you’ve been through the learning process already, what would you recommend?

I’d be very interested to hear your thoughts. Keep up the good work, it is really appreciated.

—

My reply: Dear Reader please tell me about your background, how you became interested in investing and how YOU think is the best way to learn.

What drives your interest in investing? Then I can better frame my answer.

THANKS.

—

That is a very good question and I’ll try to be as clear and honest as possible.

Background: I am from the UK, 42 years old, married, with one child.

Job: Sales & Marketing Director for a small Manufacturing Company selling custom robotics/automation machines/systems to pharmaceutical and petro/chemical industries.

Professional Background: I am a Chartered Mechanical Engineer.

Education: 2001 – First Class Honours Degree in Mechanical Engineering.

2006 – MBA from XXXXX Business School.

2010 – MSc module Valuation with Professor Glen Arnold at Salford University (10 week semester). Glen is author of “Value Investing” and other related investing/corporate finance titles (FT Pearson).

2012 – Professional Certificate in Accounting (Open University). This was a distance learning course done over two years in financial accounting (year 1) and management accounting (year 2).

Background: Hard to say how I started out, but I invested in Thatcher’s UK privatisation initiatives in the mid 80s. I made a small amount of money on this purchase of UK utility company British Gas and I was hooked. I was 16 years old.

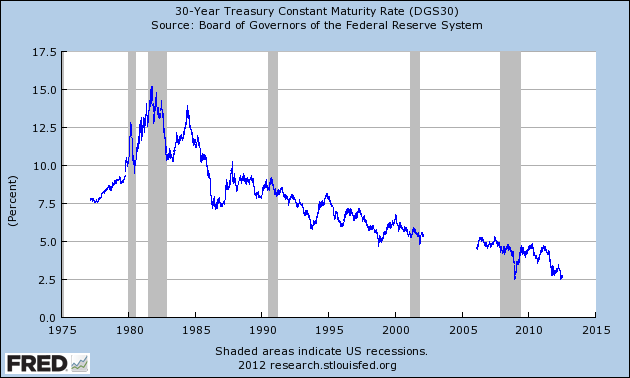

Since then I had limited free capital due to mortgage, pension and so on. About seven years ago, I became interested again and read “The Motley Fool Investment Guide” on investing which basically advocated index/mutual funds. I did this for a couple of years, invested mainly in Fidelity funds, UK, China, India, US index funds and by sheer good fortune sold out near the top of the market to buy a house (May 2007). Shortly after I had a brief spell spread betting (futures), with limited success, actually no success! I wanted to get rich quick and attended numerous trading seminars in London. I shorted one of the worst hit UK banks (RBS) during the banking crisis and still lost money because of the volatility (and my ineptitude). Imagine losing money shorting Lehman! It was that bad.

I managed to stay out of the market for 2008 and started to reinvest in 2009, mainly FTSE100 companies that are mostly popular (by volume e.g. Vodafone, Royal Bank Scotland) but with no analysis or reason to invest other than a ‘gut feel’ that they would go up! They did, but so did everything else…I later sold once I became interested or aware of small cap value.

I’ve read (once only) many classic investment books (Graham, Dreman, Lynch, Greenwald, Glen Arnold, Montier, Shefrin, Buffett partnership letters, Greenblatt, Pabrai etc.). As you know there are many references in these books to the accounting numbers and having read them I realized I didn’t know that much about accounting despite my MBA education. As a side note, I did the part-time Executive MBA and it was way too hurried to absorb the vast amount of information, so my finance learning was minimal. I oculd calculate WACC, CAPM etc., but didn’t understand the context. And so I decided to embark on an accounting distance learning course which I recently passed a couple of months ago.

After reading these books and several biographies on Buffett, I became more and more interested in the value philosophy (low P/E, P/BV etc.). I stumbled across various value oriented blogs such as Richard Beddard in the UK, Geoff Gannon and your own blog. Since reading these blogs I started to follow the UK small cap scene. (John Chew Small-caps have the tendency to be more over-or-undervalued for liquidity and informational reasons). The reasons for this philosophy are mainly based on Buffett’s early days, Greenwald, Beddard and Glen Arnold’s teachings. I can also relate to the idea that they are under researched, too small for the institutions and are a lot easier to understand.

So far my learning process has evolved from trying to understand quantitative financial analysis through books and working my way backwards, i.e. if I don’t understand something in a book or on a blog, I know I have to educate myself rather than think I know what I’m doing. I’d like to think I recognize my behavioral failings e.g. overconfidence, which I hear a lot in investing. My current thinking is to learn financial statement analysis first, along with valuation and then I can focus on the qualitative factors such as competitive advantage etc.

I believe that to buy a company cheap, you should know its intrinsic value and so I have become more interested in valuation and the teachings of Damodaran. I have just started to look at his Spring 2012 lectures. At the same time I saw his course mentioned in your first lecture. Not long after reading your first lecture, my question occurred to me, i.e. if John is recommending these resources – does he suggest that the reader works through those recommendations first before proceeding with the lectures. I realize that if you read and did everything you posted, it would take a lifetime, so although I am definitely not looking for shortcuts, I would appreciate advice on the case study approach to learning. My intention is to work through the lectures and stop at the point a book is recommended. However there are about five or six books mentioned in lecture one alone. I’ve just started, Essays of Warren Buffett by Cunningham. I also understand there is no substitute for getting your hands dirty and reading the financial reports of the companies you’ve either screened or shortlisted for some reason. I suppose I’m at the stage where I’m not sure what ratios are important, profitability vs financial strength etc. Do I look at a company qualitatively first or do I screen based on PBV, P/E, Yield, ROIC, ROE, EV/EBITDA etc.? I’m conscious that I need to avoid value traps, so maybe look at F-Score, Z-Score, solvency.

I realize you can never stop learning, but I just need some direction from a person who’s been there already. Once I have the right approach in mind, I will study and ultimately learn from my mistakes akin to Kolb’s experiential learning theory.

What drives my interest in Investing?

I suppose this could be answered with a quote from the Guy Thomas book, Free Capital:-

“Wouldn’t life be better if you were free of the daily grind – the conventional job and boss – and instead succeeded or failed purely on the merits of your own investment choices? Free Capital is a window into this world.” Guy Thomas – Free Capital.

That quote would sum it up for me. I can cope with not being rich, but being free would be pretty good! In addition, I actually love the game of investing and the intellectual challenge interests me enormously. I read investing books for fun, much to my wife’s disapproval!

I hope the above gives you enough to answer my original question and thank you for your time and help.