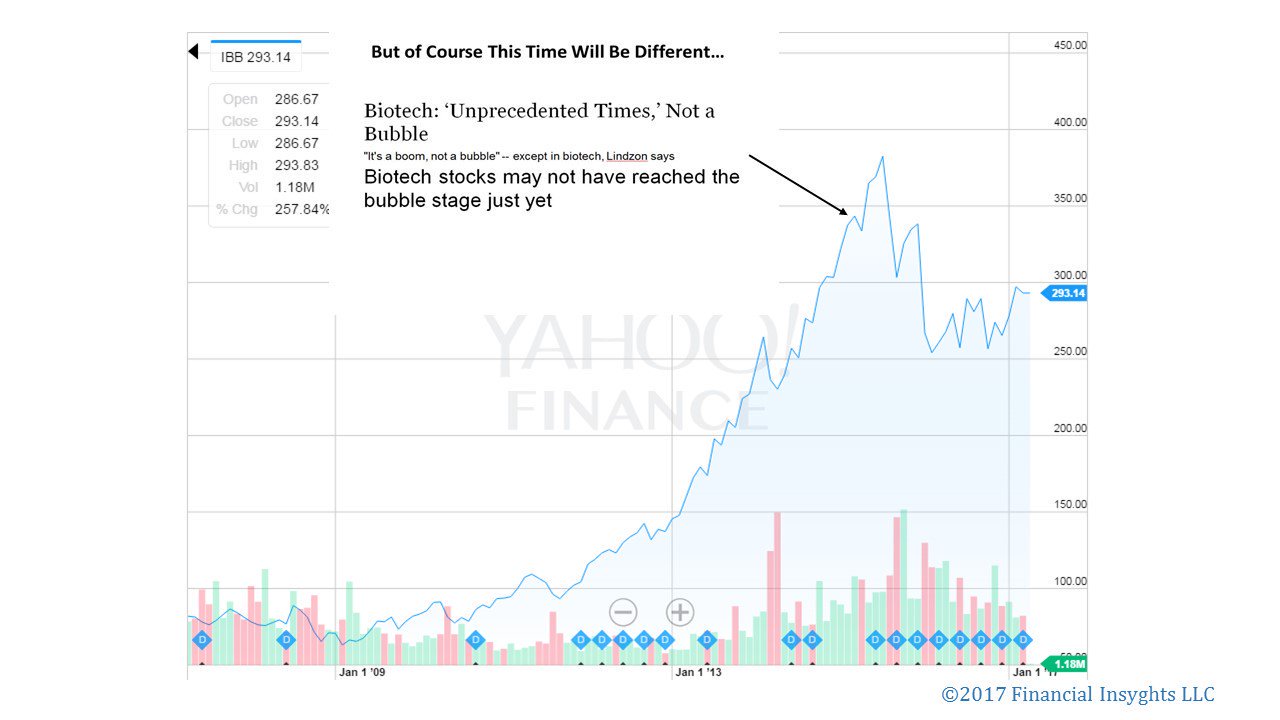

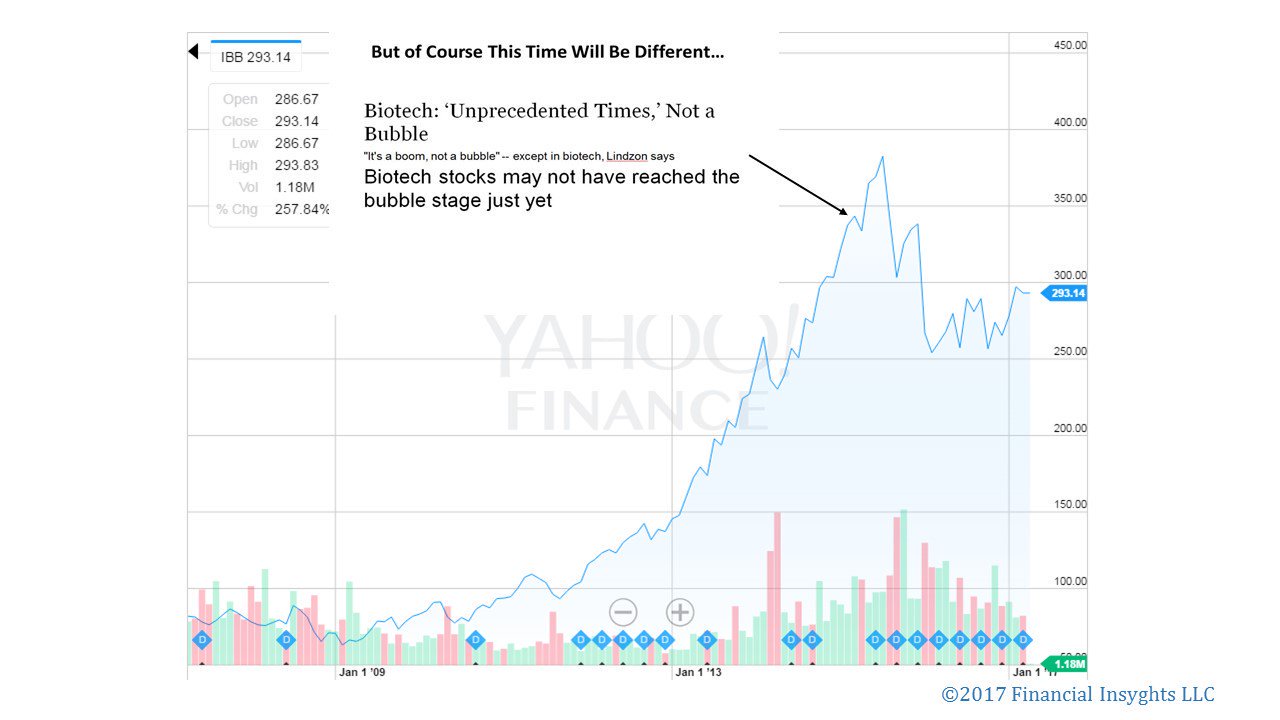

Has the meteoric rise of passive investing generated the “greatest bubble ever”?

The better we understand the baked-in biases of algorithmic investing, the closer we can come to answers.

The following article was originally published in “What I Learned This Week” on June 15, 2017. To learn more about 13D’s investment research, visit website. https://latest.13d.com/tagged/wiltw

In an article for Bloomberg View last week titled “Why It’s Smart to Worry About ETFs”, Noah Smith wrote the following prescient truth: “No one knows the basic laws that govern asset markets, so there’s a tendency to use new technologies until they fail, then start over.” As we explored in WILTW June 1, 2017, algorithmic accountability has become a rising concern among technologists as we stand at the precipice of the machine-learning age. For more than a decade, blind faith in the impartiality of math has suppressed proper accounting for the inevitable biases and vulnerabilities baked into the algorithms that dominate the Digital Age. In no sector could this faith prove more costly than finance.

The rise of passive investing has been well-reported, yet the statistics remain staggering. According to Bloomberg, Vanguard saw net inflows of $2 billion per day during the first quarter of this year. According to The Wall Street Journal, quantitative hedge funds are now responsible for 27% of all U.S. stock trades by investors, up from 14% in 2013. Based on a recent Bernstein Research prediction, 50% of all assets under management in the U.S. will be passively managed by early 2018.

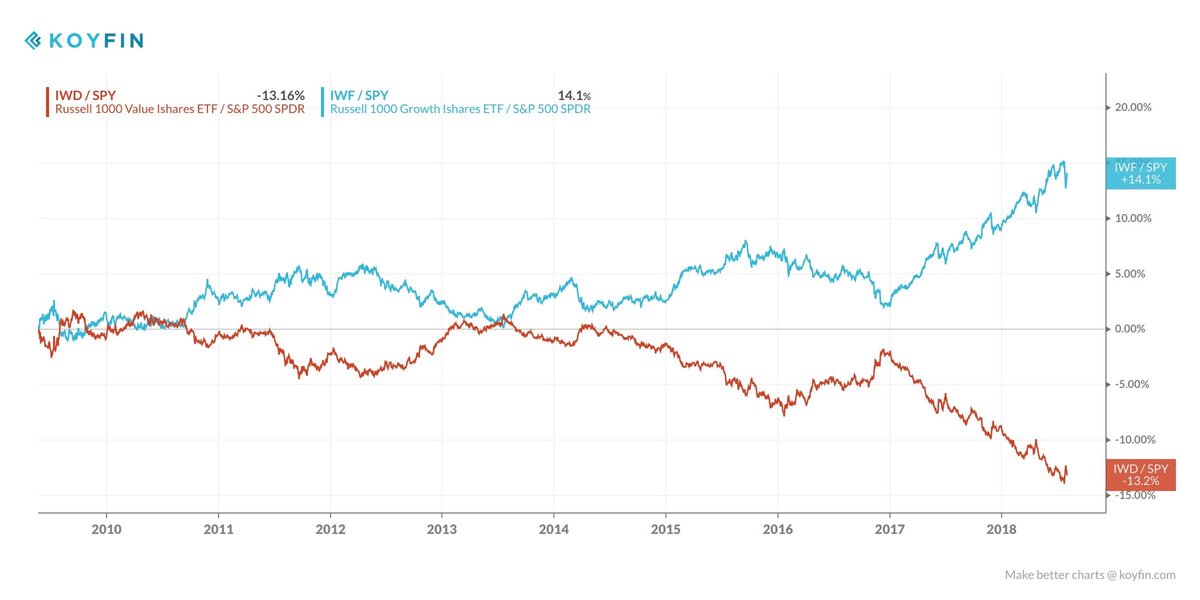

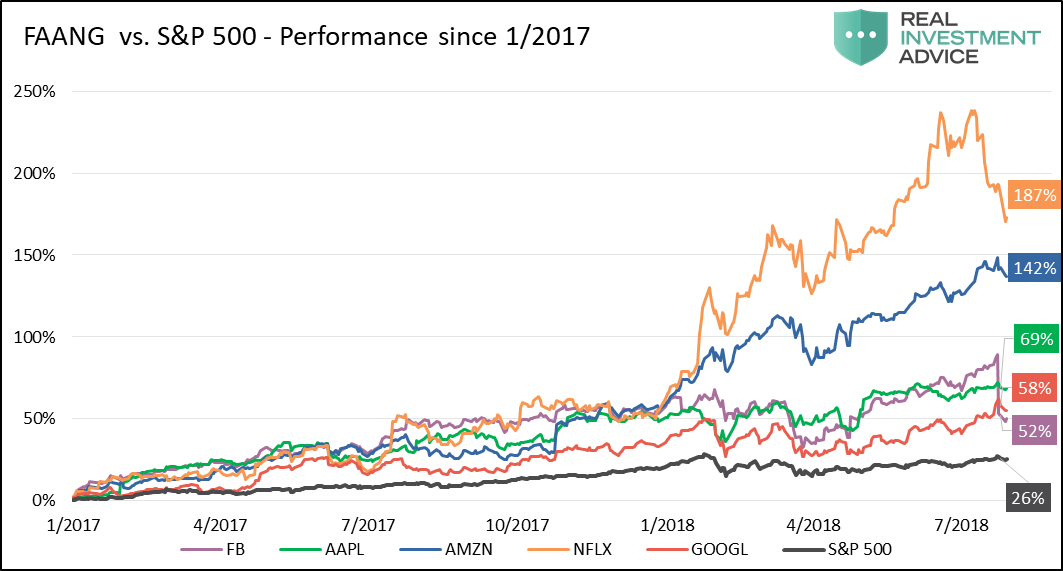

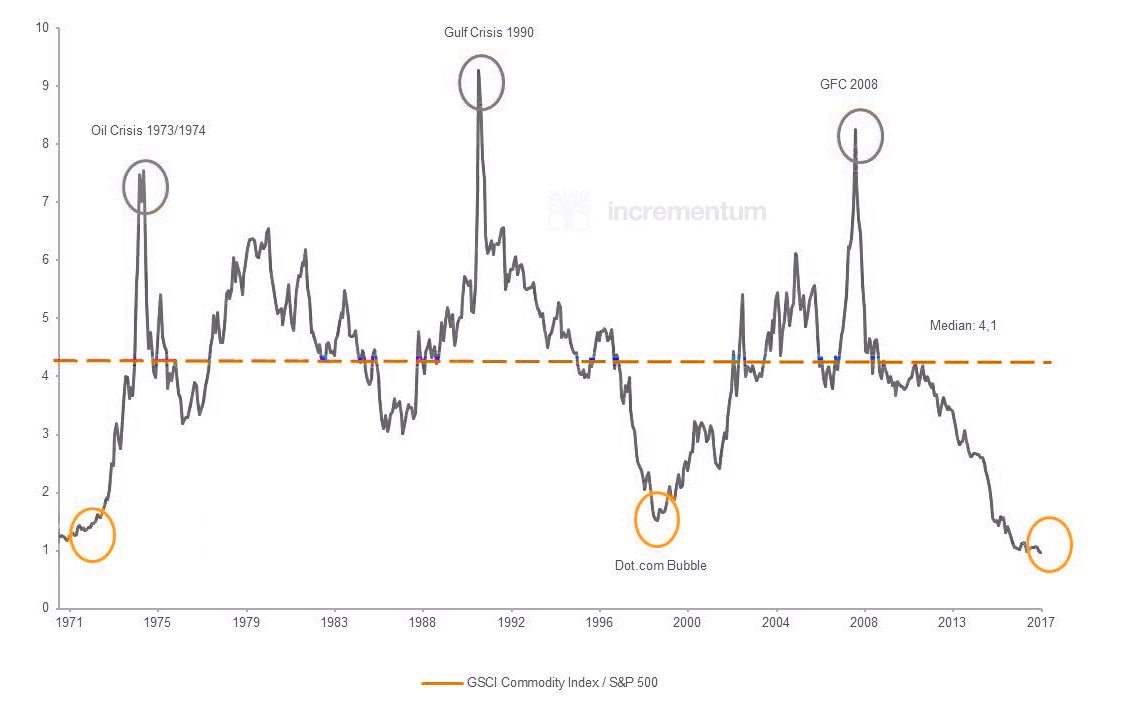

In these pages, we have time and again expressed concern about the potential distortions passive investing is creating. Today, evidence is everywhere in the U.S. economy — record low volatility despite a news cycle defined by turbulence; a stock market controlled by extreme top-heaviness; and many no-growth companies seeing ever-increasing valuation divergences. As always, the key questions are when will passive strategies backfire, what will prove the trigger, and how can we mitigate the damage to our portfolios? The better we understand the baked-in biases of algorithmic investing, the closer we can come to answers.

Over the last year, few have sounded the passive alarm as loudly as Steven Bregman, co-founder of investment advisor Horizon Kinetics. He believes record ETF inflows have generated “the greatest bubble ever” — “a massive systemic risk to which everyone who believes they are well-diversified in the conventional sense are now exposed.”

Bregman explained his rationale in a speech at a Grant’s conference in October:

“In the past two years, the most outstanding mutual fund and holding- company managers of the past couple of decades, each with different styles, with limited overlap in their portfolios, collectively and simultaneously underperformed the S&P 500…There is no precedent for this. It’s never happened before. It is important to understand why. Is it really because they invested poorly? In other words, were they the anomaly for underperforming — and is it reasonable to believe that they all lost their touch at the same time, they all got stupid together? Or was it the S&P 500 that was the anomaly for outperforming? One part of the answer we know… If active managers behave in a dysfunctional manner, it will eventually be reflected in underperformance relative to their benchmark, and they can be dismissed. If the passive investors behave dysfunctionally, by definition this cannot be reflected in underperformance, since the indices are the benchmark.”

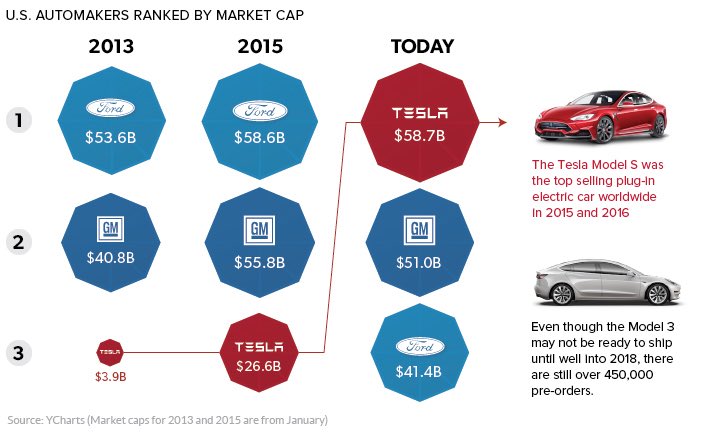

At the heart of passive “dysfunction” are two key algorithmic biases: the marginalization of price discovery and the herd effect. Because shares are not bought individually, ETFs neglect company-by-company due diligence. This is not a problem when active managers can serve as a counterbalance. However, the more capital that floods into ETFs, the less power active managers possess to force algorithmic realignments. In fact, active managers are incentivized to join the herd—they underperform if they challenge ETF movements based on price discovery. This allows the herd to crowd assets and escalate their power without accountability to fundamentals.

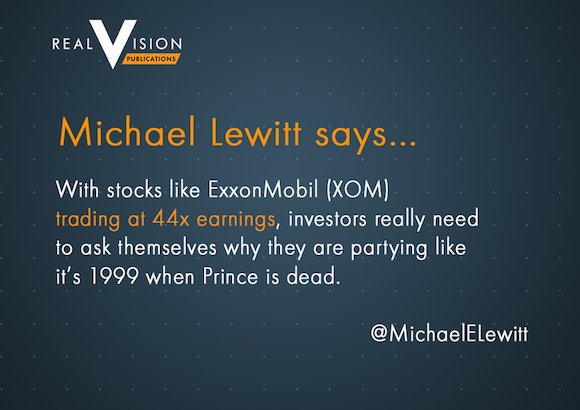

With Exxon as his example, Bregman puts the crisis of price discovery in a real- world context:

“Aside from being 25% of the iShares U.S. Energy ETF, 22% of the Vanguard Energy ETF, and so forth, Exxon is simultaneously a Dividend Growth stock and a Deep Value stock. It is in the USA Quality Factor ETF and in the Weak Dollar U.S. Equity ETF. Get this: It’s both a Momentum Tilt stock and a Low Volatility stock. It sounds like a vaudeville act…Say in 2013, on a bench in a train station, you came upon a page torn from an ExxonMobil financial statement that a time traveler from 2016 had inadvertently left behind. There it is before you: detailed, factual knowledge of Exxon’s results three years into the future. You’d know everything except, like a morality fable, the stock price: oil prices down 50%, revenue down 46%, earnings down 75%, the dividend-payout ratio almost 3x earnings. If you shorted, you would have lost money…There is no factor in the algorithm for valuation. No analyst at the ETF organizer—or at the Pension Fund that might be investing—is concerned about it; it’s not in the job description. There is, really, no price discovery. And if there’s no price discovery, is there really a market?”

We see a similar dynamic at play with quants. Competitive advantage comes from finding data points and correlations that give an edge. However, incomplete or esoteric data can mislead algorithms. So the pool of valuable insights is self-limiting. Meaning, the more money quants manage, the more the same inputs and formulas are utilized, crowding certain assets. This dynamic is what caused the “quant meltdown” of 2007. Since, quants have become more sophisticated as they integrate machine learning, yet the risk of overusing algorithmic strategies remains.

Writing about the bubble-threat quants pose, Wolf Street’s Wolf Richter pinpoints the herd problem:

“It seems algos are programmed with a bias to buy. Individual stocks have risen to ludicrous levels that leave rational humans scratching their heads. But since everything always goes up, and even small dips are big buying opportunities for these algos, machine learning teaches algos precisely that, and it becomes a self-propagating machine, until something trips a limit somewhere.”

As Richter suggests, there’s a flip side to the self-propagating coin. If algorithms have a bias to buy, they can also have a bias to sell. As we explored in WILTW February 11, 2016, we are concerned about how passive strategies will react to a severe market shock. If a key sector failure, a geopolitical crisis, or even an unknown, “black box” bias pulls an algorithmic risk trigger, will the herd run all at once? With such a concentrated market, an increasing amount of assets in weak hands have the power to create a devastating “sell” cascade—a risk tech giant stocks demonstrated over the past week.

With leverage on the rise, the potential for a “sell” cascade appears particularly threatening. Quant algorithms are designed to read market tranquility as a buy-sign for risky assets—another bias of concern. Currently, this is pushing leverage higher. As reported by The Financial Times, Morgan Stanley calculates that equity exposure of risk parity funds is now at its highest level since its records began in 1999.

This risk is compounded by the ETF transparency-problem. Because assets are bundled, it may take dangerously long to identify a toxic asset. And once toxicity is identified, the average investor may not be able to differentiate between healthy and infected ETFs. (A similar problem exacerbated market volatility during the subprime mortgage crisis a decade ago.) As Noah Smith writes, this could create a liquidity crisis: “Liquidity in the ETF market might suddenly dry up, as everyone tries to figure out which ETFs have lots of junk and which ones don’t.”

J.P. Morgan estimated this week that passive and quantitative investors now account for 60% of equity assets, which compares to less than 30% a decade ago. Moreover, they estimate that only 10% of trading volumes now originate from fundamental discretionary traders. This unprecedented rate of change no doubt opens the door to unaccountability, miscalculation and in turn, unforeseen consequence. We will continue to track developments closely as we try and pinpoint tipping points and safe havens. As we’ve discussed time and again with algorithms, advancement and transparency are most-often opposing forces. If we don’t pry open the passive black box, we will miss the biases hidden within. And given the power passive strategies have rapidly accrued, perpetuating blind faith could prove devastating.

The Greatest Bubble Ever 13D Research (Sign-up for their updates!)

—

A Reader’s question that I post below so the many intelligent folks that read this can chip in their thoughts….

The part that confuses me the most is this:

From what I gather, Greenblatt typically calculates his measurement of normal EBITDA – MCX. He then puts a conservative multiple on this, typically 8 or 10 times EBITDA-MCX. He says higher quality companies may deserve 12x or more. He often says something like “this is a 10% cash return that is growing at 6% a year. A growing income is worth much more than a flat income”. He seems to do this on page 309-310 of the notes you sent me complete-notes-on-special-sit-class-joel-greenblatt_2.

My question is: Greenblatt’s calculation of earnings (EBITDA – MCX) only includes the maintenance portion of capital expenditure. The actual cash flow may be lower because of growth capex. Yet he is assuming a 6% growing income. It seems strange to me that he calculates the steady-state income (no growth capex. Only Maintenance capex), but he assumes that the income will grow. It seems like he is assuming the income will grow 6% but doesn’t incude the growth capex in his earnings calculation. Is it logical to assume that the steady-state earnings will grow, but not deducting the cost of the growth capex from the earnings?

Answer/reply?………….