A reader asks what to do with his $150,000: http://wp.me/p2OaYY-1TE. This post is a follow-up.

First, I would do nothing until you know what you are doing. As Jim Rogers said, “Don’t do anything until you see money laying in the street.” WAIT. You can’t ask other people to value companies for you. You either learn to do that yourself within your circle of competence (The Goal of CSinvesting.org) or you find a low-cost way to be in equities.

My advice: avoid high fees. That nixes most mutual funds, hedge funds and managed money. Read more:http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-04-29/wall-street-rentier-rip-index-funds-beat-996-managers-over-ten-years

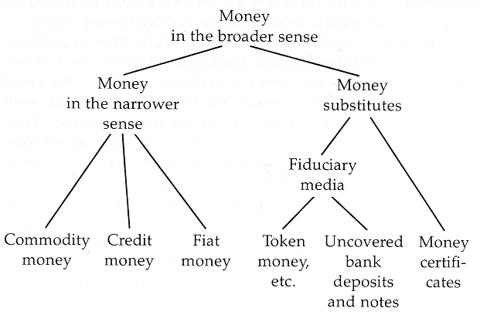

Keep it simple. There are four asset classes (Read The Permanent Portfolio) Equities, Bonds, Cash, and Gold

Equities, Bonds, Cash, and Gold

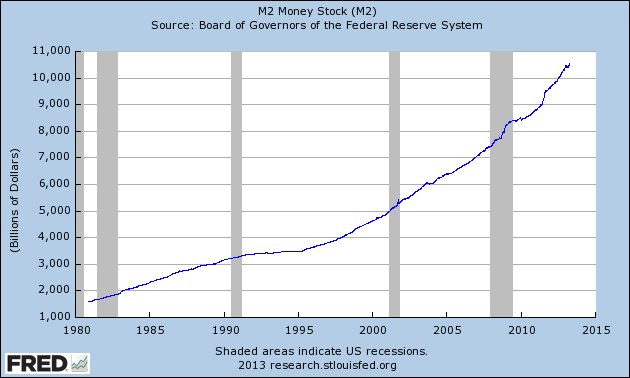

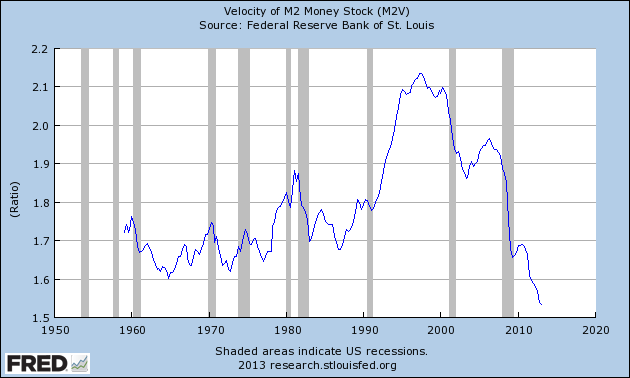

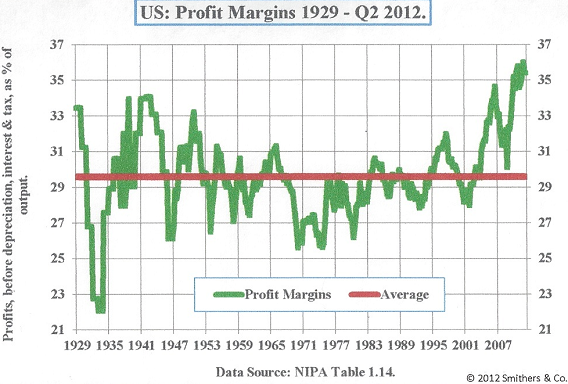

I love finding undervalued businesses, but we live in a world of monetary distortion of fiat currency wars (Japan), suppressed interest rates, hidden risks and massive debasement so I would have 5% up to 25% in gold as an insurance policy to maintain the purchasing power of my savings. Gold coins from a reputable dealer should be part of that. Buying CEF at a discount would be another low cost way to own bullion. Gold is just a commodity money that holds its value over centuries and it can’t be printed nor does it have liabilities (counter-party risk) like fiat currencies. Another way to approach it might be avoid oversupply (dollars) and buy undersupply (money that can’t be printed). Don’t take my word for it. What did an oz of gold purchased 200 years ago, 100 years ago, 50 years ago and 20 years ago? Choose a man’s suit, a night at a decent hotel and a meal as items to consider. Learn more here: http://www.garynorth.com/public/department32.cfm Follow the links to the free books and reports on gold, you will learn alot.

Now, I own some gold coins but I don’t count investments like Seabridge Gold (SA) as an insurance policy, but as an investment in gold. I can own an oz in the ground for $10 in enterprise value per share. Of course, there are plenty of risks to get an oz of gold out of the ground, but I think there is some margin of error. But I don’t recommend this strategy for others due to the need to diversify highly, know the industry, and the tremendous volatility.

Government bonds are a mass distortion on the short end and as long as other governments will hold our dollars this game can continue a long time. I would stay within a laddered bond portfolio of no more than seven years so WHEN interest rates rise, you can roll into higher yields. I would do this if you have to have cash in three to four years, and you are hedging your portfolio with this different asset class. But I think of government bonds as return-free risk. You take on risk for tiny returns. Welcome to financial repression. The Fed is punishing savers to fund the government. Corporate bonds require you to be able to read balance sheets so you are adequately paid for th credit risk.

If you are willing to do some work and have the temperament, then here is one way to invest in equities besides an index fund as Buffett has suggested:

The Eternal Secret of Successful Investing

A Little Wonderful Advice from Where Are The Customer’s Yachts? by Fred Schwed, Jr., 1940 (pages 180-182)

For no fee at all I am prepared to offer to any wealthy person an investment program which will last a lifetime and will not only preserve the estate but greatly increase it. Like other great ideas, this one is simple:

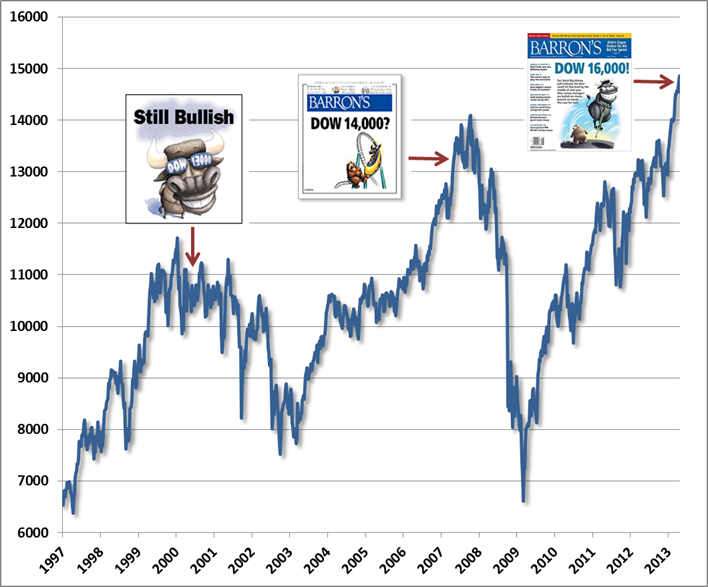

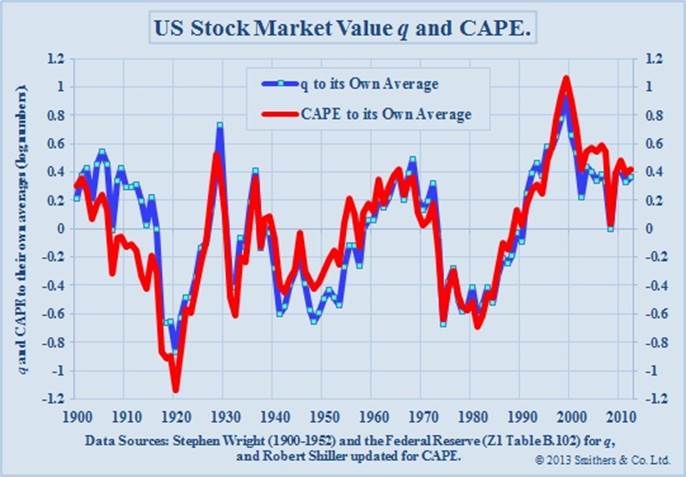

When there is a stock-market boom, and everyone is scrambling for common stocks, take all your common stocks and sell them. Take the proceeds and buy conservative bonds. No doubt the stocks you sold will go higher. Pay no attention to this—just wait for the depression which will come sooner or later. When this depression—or panic—becomes a national catastrophe, sell out the bonds (perhaps at a loss) and buy back the stocks. No doubt the stocks will go still lower. Again pay no attention. Wait for the next boom. Continue to repeat this operation as long as you live, and you will have the pleasure of dying rich.

A glance at financial history will show that there never was a generation for whom this advice would not have worked splendidly. But it distresses me to report that I have never enjoyed the social acquaintance of anyone who managed to do it. It looks as easy as rolling off a log, but it isn’t. The chief difficulties, of course, are psychological. It requires buying bonds when bonds are generally unpopular, and buying stocks when stocks are universally detested.

I suspect that there are actually a few people who do something like this, even though I have never had the pleasure of meeting them. I suspect it because someone must buy the stock that the suckers sell at those awful prices—a fact usually outside the consciousness of the public and of financial reporters. An experienced reporter’s poetic account in the paper following a day of terrible panic reads this way:

Large selling was in evidence at the opening bell and gained steadily in volume and violence throughout the morning session. At noon a rally, dishearteningly brief, took place as a result of short covering. But a new selling wave soon threw the market into utter chaos, and during the final hour equities were thrown overboard in huge lots, without regard for price or value.

The public reads the papers, and reading the foregoing, it gets the impression that on that catastrophic day everyone sold and nobody bought, except that little band of shorts (who most likely didn’t exist). Of course, there is just no truth in that at all. If on that day the terrific “selling” amounted to seven million, three hundred and sixty-five thousand shares, the volume of the buying can also be calculated. In this case it was 7,365,000 shares.

CASE STUDY

How Mr. Womack Made a Killing by John Train (1978)

The man never had a loss on balance in 60 years.

His technique was the ultimate in simplicity. When during a bear market he would read in the papers that the market was down to new lows and the experts were predicting that it was sure to drop another 200 points in the Dow, the farmer would look through a S&P Stock Guide and select around 30 stocks that had fallen in price below $10—solid, profit making, unheard of companies (pecan growers, home furnishings, etc.) and paid dividends. He would come to Houston and buy a $25,000 “package” of them.

And then, one, two, three or four years later, when the stock market was bubbling and the prophets were talking about the Dow hitting 1500, he would come to town and sell his whole package. It was as simple as that.

He equated buying stocks with buying a truckload of pigs. The lower he could buy the pigs, when the pork market was depressed, the more profit he would make when the next seller’s market would come along. He claimed that he would rather buy stocks under such conditions than pigs because pigs did not pay a dividend. You must feed pigs.

He took “a farming” approach to the stock market in general. In rice farming, there is a planting season and a harvesting season, in his stock purchases and sales he strictly observed the seasons.

Mr. Womack never seemed to buy stock at its bottom or sell it at its top. He seemed happy to buy or sell in the bottom or top range of its fluctuations. He had no regard whatsoever for the cliché’—Never send Good Money After Bad—when he was buying. For example, when the bottom fell out of the market of 1970, he added another $25,000 to his previous bargain price positions and made a virtual killing on the whole package.

I suppose that a modern stock market technician could have found a lot of alphas, betas, contrary opinions and other theories in Mr. Womack’s simple approach to buying and selling stocks. But none I know put the emphasis on “buy price” that he did.

I realize that many things determine if a stock is a wise buy. But I have learned that during a depressed stock market, if you can get a cost position in a stock’s bottom price range it will forgive a multitude of misjudgments later.

During a market rise, you can sell too soon and make a profit, sell at the top and make a very good profit. So, with so many profit probabilities in your favor, the best cost price possible is worth waiting for.

Knowing this is always comforting during a depressed market, when a “chartist” looks at you with alarm after you buy on his latest “sell signal.”

In sum, Mr. Womack didn’t make anything complicated out of the stock market. He taught me that you can’t be buying stocks every day, week or month of the year and make a profit, any more than you could plant rice every day, week or month and make a crop. He changed my investing lifestyle and I have made a profit ever since.

Keep this a secret!

—

Of course after reading those pieces, you realize there is no secret to investing. All the principles are laid out in Security Analysis and The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham. The application and evolution of value investing principles are laid out each year in Mr. Buffett’s shareholder letters. The study, application and discipline are up to you, but then who would want it any other way?

Greenblatt Offers Advice

Greenblatt Offers Advice

The BIG SECRET for the Small Investor: A New Route to Long-Term Investment Success by Joel Greenblatt (2011)

When investors decide to invest in the stock market they can:

- Do it themselves

- Give it to professionals to invest.

- They can invest in traditional index fund

- Or they can invest in fundamentally constructed indexes (recommended)

If brains, dedication and MBA degrees won’t help you beat the market, what will?

The secret to beating the market is in learning just a few simple concepts that almost anyone can master. These concepts serve as a road map that most investors simply don’t have.

Most people CAN do it. It is just that most people won’t. Why?

Understand where the value of a business comes from, how markets work and what really happens on Wall Street will provide important conclusions.

The BIG SECRET to INVESTING: Figure out the value of something—and then pay a lot less. Graham called this “investing with a margin of safety.”

In short, if we invest without understanding the value of what we are buying, we will have little chyance of making an intelligent investment. The value of an investment comes from how much that business can earn over its entire lifetime. Discounted back to a value in today’s dollars. Earnings over the next twenty or thirty years are where most of this value comes from. Earnings from next quarter or next year represent only a tiny portion of this value. Small changes in growth rates or our discount rate will lead to large swings in value.

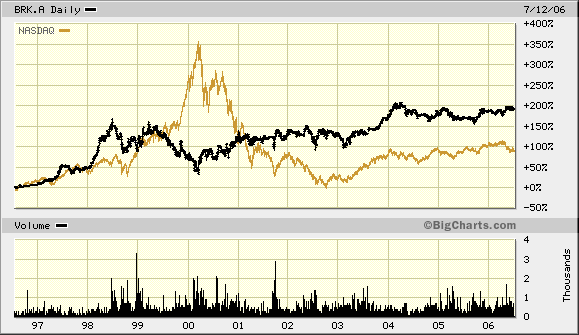

Then there is relative value. What business is the company in? How much are other companies in similar businesses selling for? Looking at relative value makes complete sense and is an important and useful way to help value businesses. Unfortunately, there are times when this method doesn’t work well. The Internet bubble of the late 1990s, when almost any company associated with the Internet traded at incredibly high and unjustifiable prices. Comparing one Internet company to another wasn’t very helpful.

In the stock market this kind of relative mispricing happens. An entire industry, like oil or construction, may be in favor because prospects look particularly good over the near term. Yet when an entire industry is misprices (like the capital goods sector during a boom), even the cheapest oil company or the least expensive construction company may bge massively overpriced!

There are other methods such as acquisition value, liquidation value, and sum of the parts, can also be used to help calculate a fair value.

By now you know it is not so easy to figure out the value of a company. How in the world do we gho about estimating the next thirty-plus years of earnings and, on top of that, try to figure out what those earnings are worth today? The answer is actually simple: We don’t.

We start with the assumption that there are other alternatives for our money. Say we can get 6%[1] for ten years from a government bond compared to a company paying a 10% earnings yield. One is guaranteed and the other is variable—which do we choose? That depends upon how confident we are in our estimates of future earnings from the company we valued or what other companies can offer us in return.

We first compare a potential investment against what we coulde earn risk-free with our money. If we have high confidence in our estimates and our investment appears to offer a significantly higher annual return over the long term than the risk free rate, we have passed the first hurdle. Next we compare our investment with our other investment alternatives.

If you can’t value a company or do not feel confident about your estimates, then skip that company and find an easier one to value.

In the stock market no one forces you to invest. Focus on those companies you can evaluate.

One way to win in the stock market game is to fly a little below the radar, to buy share in smaller companies where the big boys dimply can’t play. So investing in smaller capitalization stocks is a game involving thousands of companies worldwide, and most institutions are too big to play.

So not having billions of dollars to invest is a great way to gain an edge over the big Wall Street firms. Also, find 6 to 10 companies where you have a high degree of condidence in the prospects for future earnings, growth rates, and new industry developments.

According to Buffett, “We believe that a policy of portfolio concentration may well decrease risk if it raises, as it should, both the intensity with which an investor thinks about a business and the comfort level he must feel with its economic characteristics before buying into it.”

Besides going small (small-cap), go off the beaten path. Special situations is a anrea where knowing where to look, rather than extraordinary talent, is the most important part of finding bargains in some of these less well followed areas.

Spinoffs. The lack of research and following creates an even greater potential for mispricing of the new shares.

Stocks emerging from bankruptcy. Again, unwanted and unanalyzed stocks create a greater chance for mispriced bargains.

Restructings, mergers, liquidations, asset sales, distributions, rights offerings, recapitalizations, options, smaller foreign securities, complex securities, and many more.

Investors who are willing to do a little work have plenty of ways to gain an advantage by simply changing the game.

If you can’t do it yourself then you can choose:

Actively or passively managed mutual funds.

Most actively managed mutual funds charge fees and expenses based on the size fo the fund, usually 1 to 2 percent of the total assets under management.

Invest in index funds. However, there are problems with index investing, and

congratulations to Greenblatt for developing and explaining these problems in

terms that most investors understand. As you read this book, you will come to

appreciate the difference between market-weighted (“capitalization” weighted)

funds, equally-weighted funds and “fundamentally-weighted” funds. The

differences are not trivial, yet most investors are unaware of them.

Use Greenblatt’s approach, developed and explained in his book. However, I will say that his “value-weighted” approach, which amounts to giving more weight to investments that appear more attractively priced (lower price/earnings ratios, etc.), makes sense for many investors.

Two stand-out ideas from the book: 1) value-weighted index investing and

2)always have a core position invested at all times, which based on your market

outlook you can add or subtract to it by a given amount on rare occasions (if

you have no idea what I’m talking about–Get This Book). If retail investors

were to follow this advice to the letter, they would see their returns and peace

of mind increase dramatically, the latter being more important to overall

well-being. (Amazon reviews)

[1] Using 6 percent as a minimum threshold to beat, regardless of how low government rates go, should give us added confidence that we are making a good long term investment. (This should protect us if low government bond rates are not a permanent condition.)

END