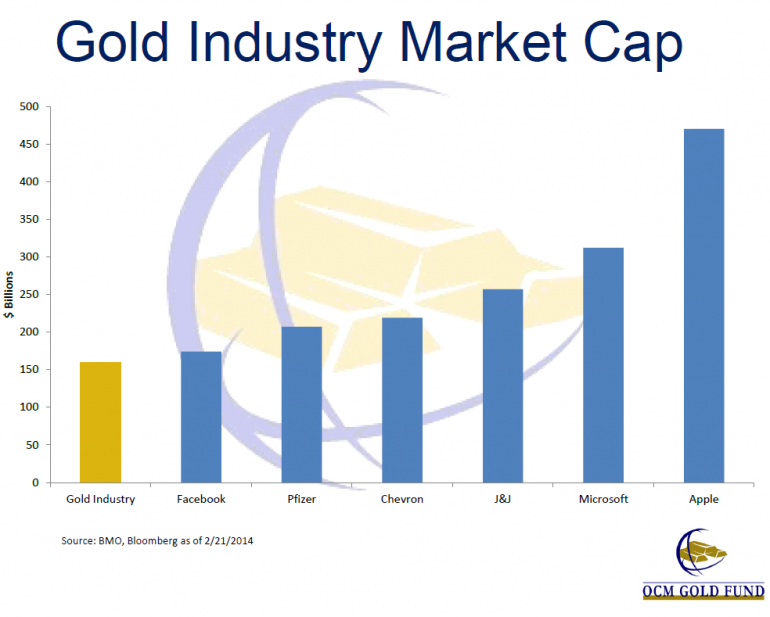

David Iben is a deep value investor currently focused on highly cyclical industries like coal, uranium, and gold mining. He has a mandate to go anywhere to invest in big or small companies. He seeks out value. The world is now bifurcated between a highly valued U.S. stock market and the cheaper emerging markets. Social media and Biotech stocks trade at rich valuations while depressed cyclical resource companies languish.

David Iben is a deep value investor currently focused on highly cyclical industries like coal, uranium, and gold mining. He has a mandate to go anywhere to invest in big or small companies. He seeks out value. The world is now bifurcated between a highly valued U.S. stock market and the cheaper emerging markets. Social media and Biotech stocks trade at rich valuations while depressed cyclical resource companies languish.

VALUATION

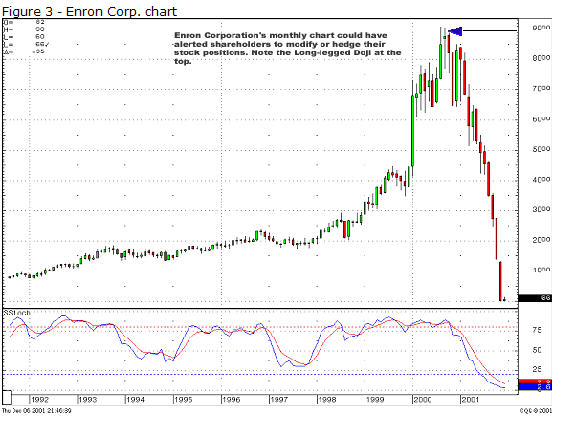

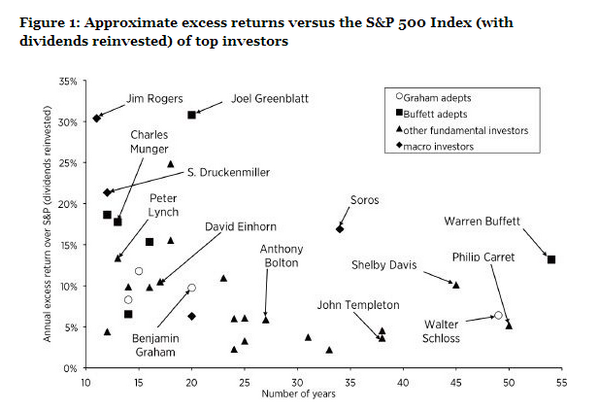

Value to us is a pre-requisite and thus we never pay more than a company’s estimated risk-adjusted intrinsic value. But, failing to think deeply and independently about what constitutes value and how best to derive it, can be harmful. Following in the footsteps of growth investors who had allowed themselves to become too formulaic or put in a box in the late 90s, some value investors were hurt by overly restrictive definitions of value in 2007 and 2008 (Price/Book and Price/Earnings, etc). We find it valuable to use many valuation metrics. Additionally, emphasis is placed on those metrics that are most appropriate to a certain industry. For example, asset heavy and/or cyclical companies often are tough to appraise using Price/Earnings or Price-to-Cash Flow. Price to book value, liquidation value, replacement value, land value, etc. usually prove helpful. These metrics often are not helpful for asset light companies, where Discounted Cash Flow scenario analysis is more useful. Applying these metrics across industries, countries, and regions helps illuminate mispricing. Looking at different industries through different lenses, through focused lenses, using industry appropriate metrics and qualitative factors is important. Barriers to entry are an important factor. Potential winners possess different key attributes. Supply and demand are extremely important detriments of margin sustainability. The investor herd has a strong tendency to use trend line analysis, assuming that past growth will lead to future growth. A more reasoned, independent assessment will often foretell margin collapses as industries overdo it, thereby sowing the seeds of their own self-destruction.

Currently, opportunities are being created when the establishment pays too little heed to supply growth. This fallacy extends to money. Many seem to believe that the Federal Reserve has succeeded in quintupling the supply of dollars without a loss of intrinsic value. That is impossible. Evidence of the loss of value is abundantly clear. Gold supply held by the U. S. Treasury has not increased. As economic theory would predict, the price of gold went up. Following 12 straight years of advance and apparently overshooting, the price has since corrected 40%. The trend followers have their rulers out again, confusing a correction in a supply/demand induced uptrend with a new counter-trend.

We view this as opportunity. At the same time, bonds are priced as if they were scarce rather than too abundant to be managed. It is no secret that this is due to open, market manipulation by the central banks. Intrinsic value must eventually be reflected in market prices. These are abnormally challenging times. Fortunately, we believe markets aren’t fully efficient.

—

If you listen to his conference calls and read his insights, you will have a great education in counter-cyclical investing. It is easy to know what to do but hard to do!

Value Investor Insight_3.31.14 Kopernik (Interview)

July 2014 The Contrarian Iben of Kopernik (Interview)

Kopernik Annual Report 10 31 14 – Web Ready

Kopernik Semi-Annual Report _4.30.2014_FINAL

2014 – 4th Q Call with DI – Transcript FINAL

A tutorial of Deep Value Investing in Highly Cyclical Assets/Companies

The trials, tribulations, and need for consistent approach.

http://kopernikglobal.com/content/news-and-views-iben-insights

http://kopernikglobal.com/content/news-and-views-news

—

I will be asking for your suggestions for the deep value course. I am collating one reader’s suggestions which I will post next. Some of you may be quite experienced and advanced investors who tire of the theoretical course materials as well as the mechanical aspect of quantitative investing. We will discuss this next………….Thanks for your patience.