Fractional Reserve Banking and the Fed

Prof. Joe Salerno’s Testimony to Congress on the problems caused by Fractional Reserve Banking and the Federal Reserve. Fractional reserve banking causes term structure risk–customers can withdraw their money immediately but the bank creates loans at multiples of its customers’ deposits for periods longer than a day. Banks can create money out of thin air by creating these loans. Therefore, our system in buffeted by inflationary bubbles and debt collapses. Readers will learn why our financial system is infected with booms and busts. Prof. Salerno presents a solution to our Ponzi financial system. Transcript here:

Fractional Reserve Banking and The Fed_Salerno

Video of Austrian Economists’ testimony on Fractional Reserve Banking, including Prof. Salerno’s testimony (excellent): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jVm3Yzjq8zE

Sprott Asset Management on Economic Policy

The Solution is the Problem by Sprott Asset Management

http://www.sprott.com/markets-at-a-glance/the-solution%E2%80%A6is-the-problem,-part-ii/

….In today’s overleveraged world, greater deficits and government spending, financed by an expansion of public debt and the monetary base (“the printing press”), are not the answer to our economic woes. In fact, these policies have been proven to have a negative impact on growth.

No wonder bankers are reviled: http://nymag.com/news/intelligencer/encounter/jamie-dimon-2012-8/

—–

The Freeman | Ideas On Liberty, http://www.thefreemanonline.org

Boom and Bust: Crisis and Response

by Gerald P. O’Driscoll, Jr.• March 2010 • Vol. 60/Issue 2

America has experienced a classic economic boom and bust, which I first chronicled in the November 2007 Freeman [1].

Ill-conceived policies to encourage homeownership channeled cheap credit into housing markets. Land-use and zoning policies restricted the supply of housing in key desirable markets. In The Housing Boom and Bust, Thomas Sowell of the Hoover Institution has shown how these policies brought about a crisis in housing and finance.

Others have told the story from a number of perspectives and with varying emphasis on different factors. My purpose here is to focus on the policy responses to the crisis and ask whether they have been helpful or harmful.

TARP

On October 3, 2008, Congress enacted the law creating TARP (the Troubled Asset Relief Program), which was authorized to spend up to $700 billion to purchase troubled assets from financial institutions. A little more than a month later, then-Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson announced that rather than buying troubled assets, the Treasury would use the money for capital injections into banks in return for preferred shares.

Regardless of one’s attitude toward bailouts generally, Paulson’s original plan was a recipe for disaster. To help the banks he would have needed to overpay for the assets to the detriment of the taxpayers. If he had paid then-current prices, accounting rules would have forced all firms holding such assets to write them down (not just those selling the assets). Financial institutions holding dubious mortgage-backed assets were desperately trying not to write them down because that might have threatened their depleted capital base. It is fair to say that Paulson failed to grasp the underlying problems at these institutions when he first proposed the program.

TARP became a capital-relief plan. It harkened back to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) of the Great Depression. Under Jesse Jones and in conjunction with Franklin Roosevelt’s Bank Holiday, all the nation’s banks were examined and divided into the good, the bad, and the ugly. Call it his version of a “stress test.” Those deemed beyond hope were never reopened. Those troubled but salvageable were eligible for RFC capital injections. Jones also extracted resignation letters from senior management of institutions being bailed out. If he deemed existing management best suited to run the bank, it could stay. If not, it was replaced.

In comparison, Paulson’s strategy was “ready, shoot, aim.” Banks received government injections of money to replace depleted capital, with nothing explicit extracted in return. There were vague promises that banks would resume lending but there was nothing enforceable. The banks were stress-tested only after having received government funds. There were second and even third rounds of bailouts for some banks, indicating they had been weaker than thought. We know that at least one—CIT, a financial institution that received $2.3 billion in TARP money—should have been allowed to close. Instead it eventually filed for bankruptcy, and the taxpayer funds were lost.

Moreover, in what has become a national disgrace, existing management at bailed-out banks remained in place. The Bush administration failed to impose even the level of control exercised under FDR.

On the one-year anniversary of the announcement of Paulson’s reversal on TARP, I was asked by Newsweek for my assessment [2]. “It hasn’t done what [Paulson] said it would,” I said. “Yes, it saved some banks from going under, but did it restore the health of the banking system? Absolutely not.” I stand by that assessment today.

What Does Government Stimulate?

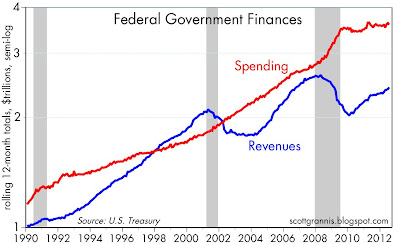

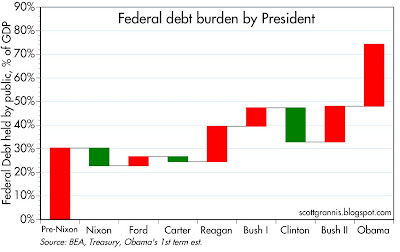

The fiscal response to the crisis of the Bush/Obama administrations has been to spend their way out of the recession. In the process the nation’s debt has skyrocketed. There are deficits and debt as far as the eye can see, and our children’s future has been mortgaged. The 2009 fiscal deficit was double that of 2008. It is running at 10 percent of GDP, and former Fed governor and Bush adviser Larry Lindsey estimates deficits will run at 7 percent of GDP for a decade.

Because of the work of Milton Friedman and his monetarist followers, countercyclical fiscal policy fell under a cloud. First, they argued that recessions are difficult to forecast and we only typically know we have entered one after the fact. The monetarists also argued that fiscal policy was subject to the cumbersome legislative process and thus could not be quickly implemented. Once spending began, its effects were only felt slowly. All this wisdom was forgotten in the panic of the Bush administration and then more so in the Obama administration.

The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, passed in February of that year, mainly sent $100 billion in checks to households in early summer to stimulate consumption and jump-start the economy. As Stanford economist John Taylor, author of Getting Off Track, has shown, the money did nothing and the economy slid into recession later that year. Any economist worth his salt knows that temporary government cash infusions will likely be saved and at best have transitory effects on spending.

Undaunted by that failure, the Obama administration decided to up the ante on the theory that there had just not been enough fiscal stimulus. It replaced billions in spending with trillions in spending: the stimulus package added on to TARP. In the next section I also discuss Fed spending masquerading as monetary policy.

What is the record? It appears that the recession may have ended in the third quarter of 2009. That would make it less than one year in duration–not atypical in that sense. Most of the Obama stimulus money has yet to be spent. (Recall Friedman’s arguments on fiscal policy.) It may be good electoral politics to claim credit for a still-nascent recovery. But it is poor economics. More likely, the self-adjusting forces of the market have been at work.

Clearly, nothing the government has done has been able to lower the unemployment rate. GDP is an abstraction; being out of work is a reality. In October the unemployment rate exceeded 10 percent. (It fell back to 10 later.) A broader measure of unemployment exceeded 17 percent. These numbers put the flesh on the skeleton of policy debates. More ominously, we now are seeing indications that wage rates are falling. As the Wall Street Journal reported [3], Professor Kenneth Couch of the University of Connecticut estimates that displaced workers returning to work will on average take a 40 percent pay cut.

Double-digit unemployment rates and double-digit wage cuts are depression statistics. In what way is government spending “stimulating”? In an editorial the Wall Street Journal concluded that “no matter how hard or imaginatively the Administration spins, the reality is that the stimulus has been the economic bust that critics predicted it would be.”

Indeed, the labor story helps us to see the dark side of stimulus spending. A good chunk of it has gone to state governments to support bloated budgets in the face of collapsing revenues. Those fiscal transfers are being done, at least in part, to placate public-sector unions, which want to protect the incomes and pensions of their members.

Fiscal stimulus has failed. What about the monetary variant?

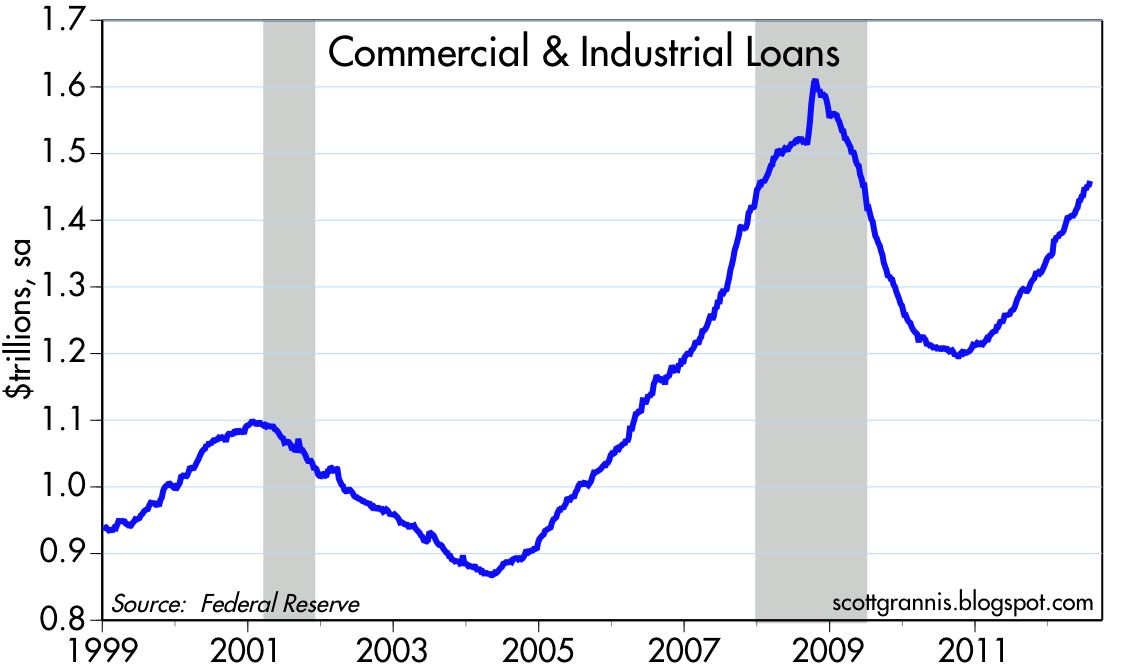

Monetary Stimulus

The Fed’s response to the crisis has drawn mixed reviews among free-market economists. Some approve of the Fed’s easing in 2008–09 as a response to an increased demand for money (falling velocity). Nearly all market-oriented economists are disquieted by the explosion of the Fed’s balance sheet as it takes on more and more assets of dubious quality. It will be extremely difficult for the central bank to dispose of such assets when it inevitably comes time for it to tighten. The Fed will likely suffer losses, and such losses impact the taxpayer. (The Fed’s surplus is paid to the Treasury.)

Many economists have been critical of the Fed for its targeted-credit policies, which amount to credit allocation. They favor one sector at the expense of others, and constitute fiscal policy rather than monetary policy. The Fed’s leadership is dismayed at its loss of approval by the general public and fears calls for greater political oversight. But the backlash is of the Fed’s own making.

In the end its fortunes are tied to the economy’s. Most Americans do not know the technicalities of monetary policy. But Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke has taken an active and public role in defending the policy response to the crisis (under both Bush and Obama). Under Bernanke the Fed has promised much and delivered little.

Just as Americans fear the spending and budget deficits, many understand that easy money helped get us into the crisis. Now Dr. Bernanke has prescribed the strongest dose of cheap money ever administered. How can the elixir that caused the boom cure the bust?

The Bernanke Fed is engaged in a policy of reflating (re-inflating) the economy: stimulating money demand to restart economic growth. It justifies the policy on the basis of Professor Bernanke’s own research that shows the evils of deflation. But what prices is he trying to prop up? All prices? Even in hyperinflations, some prices fall. Is he trying to prevent downward adjustment in wages? As suggested above, wage rates in hard-hit sectors may be falling at double-digit rates. Is he preparing for double-digit price inflation? If so, gold is underpriced at $1,000 an ounce.

Astute observers increasingly fear that what is being reflated is another asset bubble. At present, the asset bubble is concentrated in commodities (such as gold, copper, and oil) and Asian real estate. In what is known as a carry trade, global investors are borrowing dollars at low interest rates to invest in property in cities like Hong Kong and Singapore. Instead of bringing prosperity to Americans, the Fed’s policy is fueling speculation. Instead of production in the United States, the Fed’s easy money is creating paper wealth for Asian property owners.

The rise in commodity prices is perhaps most ominous. The U.S. economy remains weak and unemployment elevated. Yet Americans are already paying higher prices for gasoline. They are facing the prospect of renewed inflation and economic weakness: stagflation. That would be an updated version of the economy of the 1970s. The Fed is thereby impoverishing Americans. Is it any wonder many are calling for a reconsideration of its role?

A version of this article previously appeared on TheFreemanOnline.org on Nov. 23, 2009.

Article printed from The Freeman | Ideas On Liberty: http://www.thefreemanonline.org

URL to article: http://www.thefreemanonline.org/features/boom-and-bust-crisis-and-response-3/

URLs in this post:

[1] I first chronicled in the November 2007 Freeman: http://www.tinyurl.com/npnog4

[2] I was asked by Newsweek for my assessment: http://www.newsweek.com/id/222321

[3] As the Wall Street Journal reported: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125798515916944341.html

The Freeman | Ideas On Liberty

http://www.thefreemanonline.org

Subprime Monetary Policy

by Gerald P. O’Driscoll, Jr.• November 2007 • Vol. 57/Issue 9

In recent years monetary policy has been conducted so as to create an expectation that the Federal Reserve will bail out investors when asset bubbles deflate. Investors have come to bank on the Fed’s backing of risky ventures. The recent crisis in the subprime mortgage market is at least partly the outcome of this new approach to monetary policy. That crisis has already had widespread ramifications for homeowners and investors.

Government programs and policies often serve to insulate individuals from the full consequences of their actions. For instance, subsidized federal flood insurance leads individuals to build more homes in flood plains than would otherwise be the case. The public naturally feels sympathy for homeowners who are the victims of flooding, and supports more assistance for those caught up in these dreadful situations. The “help” often exacerbates the problem, however, by removing incentives for homeowners to rebuild on higher and drier land. The general public wonders why the catastrophes appear more frequently. Pundits ascribe them to global warming, and nature is blamed for the effects of manmade policy.

Since the 1930s the federal government has insured bank deposits. That scheme inherently reduced the vigilance of bank depositors toward their banks, removing constraints on risk-taking by the insured depository institutions. The situation became acute in the 1980s and 1990s, when unconstrained risk-taking by banks and thrift institutions led to a series of banking and financial crises. Eventually the deposit-insurance system was reformed and banking put on a sounder basis. Now we are in need of a reform of monetary policy.

Crisis in the Mortgage Market

Last February the popular press discovered subprime mortgage loans (see box) when two major originators of such loans, HSBC Holdings PLC and New Century Financial, disclosed increased loan loss provisions. HSBC is a globally diversified financial company. While it was a large lender in the market, the aggregate amount of its subprime loans was not a significant portion of its total portfolio.

New Century Financial fared much less well because of the concentration of its lending in this risky category. Its stock price collapsed after problems surfaced the previous February, and the company eventually declared bankruptcy.

Other lenders in the subprime market experienced difficulties. Fears of a housing collapse and even an economic recession grew as investors gauged the size and extent of the problem in the mortgage market.

The crisis was foreseen by many. For more than a year before the bust, bankers, analysts, and even regulators knew they had a mess in the making. As John Makin of the American Enterprise Institute observed, the lending practices in the subprime market were “shoddy and absurd.”

Lewis Ranieri, former chairman of Salomon Brothers, echoed those comments: “We’re not really sure what the guy’s income is and . . . we’re not sure what the house is worth. So you can understand why some of us become a little nervous.” Ranieri helped pioneer the bundling of mortgages into marketable securities (“securitization”), so he should know!

The collapse of the subprime mortgage market is the latest in a series of financial bubbles whose existence reflects, at least in part, moral hazard in financial markets. Moral hazard is the outcome of explicit or implicit guarantees to investors. At one time, deposit insurance was a major culprit. Today, monetary policy is fostering moral hazard.

Moral hazard occurs when some action or policy alters the behavior of individuals in a counterproductive way. Specifically, a policy intending to mitigate risk causes individuals instead to assume more risk. For example, a poorly designed policy insuring against fire could lead individuals to diminish resources devoted to fire prevention. In that case, the insurance would increase the probability of the insured risk occurring. (Of course, well-designed insurance policies should reduce risk. And in competitive markets, that is what normally happens.)

Earlier financial crises were the effects of deposit insurance and bank-closure policies that effectively insulated depositors and even other bank creditors from risk in the event of the failure of depository institutions. In an October 2002 speech to economists in New York, then-Fed Governor Ben Bernanke described the savings-and-loan crisis of the 1980s as “a situation . . . in which institutions can directly or indirectly take speculative positions using funds protected by the deposit insurance safety net—the classic ‘heads I win, tails you lose’ situation.” After an intellectual and political battle of more than a decade, the deposit-insurance loophole was sealed.

To better understand moral hazard, consider the case of a gambler going to a casino. If he bears the losses, his bets will be constrained by that risk. If someone were to guarantee him against loss, but allow him to keep the profits, the gambler would have an incentive to make the riskiest possible bets. He gains all the profits but bears none of the losses. One might designate such a system as “casino capitalism.” Current Fed policy has encouraged casino capitalism in the housing market.

Monetary policy can generate moral hazard if it is conducted so as to bail investors out of risky and otherwise ill-advised financial commitments. If investors come to expect that the policy will persist, they will deliberately take on additional risk without demanding commensurately higher returns. In effect, they will lend at the risk-free interest rate on risky projects, or at least at a lower rate than would otherwise be the case. Too much risky lending and investment will take place, and capital will be misallocated.

Money and Prices

To simplify a complex theoretical issue, an ideal monetary policy is one that facilitates and does not distort economic decision-making by individuals. Market prices play a critical role in that process by signaling to everyone the relative scarcity of goods and urgency of ends.

Austrian economist and Nobel laureate in economics F. A. Hayek characterized the price system as a communications mechanism for transmitting information about economic values. By communicating that valuable information, the price system helps coordinate economic activities. In its simplest formulation, prices tend to bring about equality between supply and demand in each market.

As with any communication system, it is desirable to filter out “noise,” extraneous signals that interfere with communication. Money is indispensable to price formation, but money can generate noise along with information. The ideal monetary policy is one in which there is no noise, only valid price signals. The best possible monetary policy would maximize the signal-to-noise ratio.

Monetary noise comes about when policy changes the value of money. In economies on gold or silver standards, the discovery of new sources of the precious metal can set in motion forces leading to an expansion of the money supply and the depreciation in the value of money. In modern times, money is created by printing it, or through expansion of bank liabilities. In nearly all developed countries, the rate of that expansion is (or can be) controlled by central banks.

Changes in the value of money create monetary noise because investors and ordinary individuals mistake changes in money prices for changes in relative prices. For instance, during inflation prices will rise just to reflect the increase in money and not necessarily because there has been a shift in preferences.

Current monetary policy is much improved from the record of the late 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s. That was the era of double-digit inflation and sky-high interest rates. In a December 2002 speech to the Economic Club of New York, then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan put monetary policy in historical context:

Although the gold standard could hardly be portrayed as having produced a period of price tranquility, it was the case that the price level in 1929 was not much different, on net, from what it had been in 1800. But, in the two decades following the abandonment of the gold standard in 1933, the consumer price index in the United States nearly doubled. And, in the four decades after that, prices quintupled. Monetary policy, unleashed from the constraint of domestic gold convertibility, had allowed a persistent overissuance of money. As recently as a decade ago, central bankers, having witnessed more than a half-century of chronic inflation, appeared to confirm that a fiat currency was inherently subject to excess.

Some scholars have suggested that money influences not only the prices of consumer goods and wages, but also asset prices. They argue that money can work its mischief without showing up in consumer goods inflation. Widely used price indices, such as the consumer price index (CPI), do not include asset prices. A stable price index of consumer goods would thus not be a good measure of the value of money. Professor Charles Goodhart pointed to the two-decade experience of Japan, in which consumer prices were stable while asset prices fluctuated wildly. He asked rhetorically what the meaning of “inflation” is in such a context.

Goodhart argued that at least one category of assets figures so large in consumer purchases that it cannot be ignored: housing. Rental prices and housing prices do not always move in tandem. Home prices are affected by monetary policy in a number of ways, most notably through interest rates.

If asset prices are not incorporated into measures of inflation, their movements will not be action-forcing events for policymakers. Fed chairmen will wring their hands about “irrational exuberance,” but will be powerless to do anything until the effects of asset-price changes are manifested in undesirable changes in current prices and output.

The Greenspan Doctrine

The new moral hazard in financial markets has its source in what can be best described as the Greenspan Doctrine. It was clearly enunciated by Greenspan in his December 19, 2002, speech, in which he made an asymmetric argument leading to an asymmetric monetary policy. He argued that asset bubbles cannot be detected and monetary policy ought not in any case to be used to offset them. The collapse of bubbles can be detected, however, and monetary policy ought to be used to offset the fallout.

Two months earlier Ben Bernanke had made a similar argument. He endorsed the Greenspan Doctrine, arguing against the use of monetary policy to prevent asset bubbles: “First, the Fed cannot reliably identify bubbles in asset prices. Second, even if it could identify bubbles, monetary policy is far too blunt a tool for effective use against them.” Since Bernanke is now Fed chairman, it is reasonable for market participants to assume that the Greenspan Doctrine still governs current Fed policy.

Wrong Question

The two men were surely asking and answering the wrong question. They were implicitly treating bubbles as solely the consequences of real shocks or disturbances. (An example of a real shock is a technological innovation leading to productivity gains and higher future expected profits in a sector.) They asked whether monetary policy should be used to offset the effects of real shocks and concluded that it should not. The latter is the correct answer to the question they each posed.

A different question would be whether monetary policy should be conducted so as to create or exacerbate asset bubbles, which would not have occurred or would have been milder absent the assumed monetary policy. The answer to that question is surely no. Consider Bernanke’s apt characterization of moral hazard in the context of the deposit-insurance crisis: “When this moral hazard is present, credit flows rapidly into inelastically supplied assets, such as real estate. Rapid appreciation is the result, until the inevitable albeit belated regulatory crackdown stops the flow of credit and leads to an asset-price crash.”

Bernanke could have been talking about the subprime-mortgage market. That bubble and collapse cannot, however, be blamed on deposit insurance. First, deposit insurance is no longer systematically mispriced and banking supervision has improved. Second, the majority of mortgages are no longer made by insured depository institutions. Yet something generated the moral hazard that enabled shoddy underwriting of subprime mortgages to persist for years.

The Greenspan Doctrine helped create moral hazard in housing finance. The Fed announced that it will take no action against bubbles, but will act aggressively to offset the consequences of their collapse. In effect the central bank is promising at least a partial bailout of bad investments. The logic of the old deposit-insurance system is at work: policymakers should protect investors against losses, no matter their folly. Or, in Greenspan’s own words: monetary policy should “mitigate the fallout [of an asset bubble] when it occurs and, hopefully, ease the transition to the next expansion.”

In the present context, the “next expansion” could also be rendered as “the next asset bubble.” If the Fed promises to “mitigate the fallout” from “irrational exuberance,” then it is rational for investors to be exuberant. Investors may be at risk for some loss, as with a deductible on a conventional insurance policy, but losses are still being mitigated.

Rate Cut in 2000

The Fed cut the Fed Funds rate sharply after the bursting of the stock market bubble in March 2000. In the eyes of many, the Fed cut rates too far and held them down too long, fueling not only a vigorous economic expansion but also the housing bubble. In his December 2002 speech, Greenspan was at pains to deflect any argument that the Fed was inflating a housing bubble. “To be sure,” he acknowledged, mortgage debt was high relative to household income [remember the date] by historical norms. But “low interest rates” were keeping the servicing requirements of the mortgage debt manageable (emphasis added). “Moreover, owing to continued large gains in residential real estate values, equity in homes has continued to rise despite very large debt-financed extractions.”

How wrong the Fed chairman was! If Greenspan was not worried about interest rates resetting, why should mortgage bankers and homeowners worry? It would have been reasonable to read into the chairman’s musings an implicit guarantee of continued low rates. A homeowner is certainly entitled to bet his home on the come if he wants. Should the central bank encourage such behavior?

Monetary Policy for a Free Economy

In his 2002 speech to the Economic Club of New York, Greenspan spoke disapprovingly of a policy that permits prices to nearly double in two decades. At current CPI inflation rates, however, prices will double in less than three decades. If inflation were to rise to 3 percent and remain there, prices would double in 24 years. That is not much progress against inflation, and surely we can expect better.

In a vibrant market economy with technological innovation and ever-new profit opportunities, the monetary policy that maintains true price stability in consumer goods requires substantial monetary stimulus. That stimulus will have a number of real consequences, including asset bubbles. These asset bubbles have real costs and involve misallocations of capital. For example, by the peak of the tech and telecom boom in March 2000, too much capital had been invested in high-tech companies and too little in “old-economy firms.” Too much fiber-optic cable was laid and too few miles of railroad track were laid.

By 2002 the Fed was worried about the possibility of price deflation and introduced a strong anti-deflationary bias. A tilt to stimulus was understandable at the time. A continued bias against deflation at any cost, however, will produce a continued bias upward in price inflation. The inflation rate begins at the positive number. With the bursting of each asset bubble and the fear of deflationary pressure, Fed policy must ease. The Greenspan Doctrine prescribes a stimulative overkill that begins the cycle anew. The Greenspan-era gains against inflation will then prove to be only temporary. His doctrine will be the death of his legacy, a legacy that already includes a housing bubble and its aftermath.

Article printed from The Freeman | Ideas On Liberty: http://www.thefreemanonline.org

Why California is bust

http://www.voiceofsandiego.org/education/article_c83343e8-ddd5-11e1-bfca-001a4bcf887a.html