Presentation on Brick

http://greenbackd.com/2012/11/26/the-brick-ltd-up-118-percent-on-guy-gottfrieds-recommendation/

Gottfried_TheBrick_VICNY2011 (3) (Powerpoint)

Tap dancing to work (Buffett Interview on Charlie Rose) http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/12672

Buffett Opines on Raising Taxes (Comments in Italics)

When taxes change, would-be investors will certainly change their decisions about where to direct capital, even “though the companies’ operating economics will not have changed adversely at all.” Buffett saw this clearly in 1986, with respect to Berkshire’s own investment decisions; it’s hard to believe that Buffett no longer believes that today, with respect to private investors.

November 25, 2012

A Minimum Tax for the Wealthy By WARREN E. BUFFETT

SUPPOSE that an investor you admire and trust comes to you with an investment idea. “This is a good one,” he says enthusiastically. “I’m in it, and I think you should be, too.”

Would your reply possibly be this? “Well, it all depends on what my tax rate will be on the gain you’re saying we’re going to make. If the taxes are too high, I would rather leave the money in my savings account, earning a quarter of 1 percent.” Only in Grover Norquist’s imagination does such a response exist.

It’s a catchy opener, attracting headlines and guffaws from the expected quarters. But I’m struck by his opener because I can think of at least one real-world example in which a rich investor nearly spiked a deal due to taxes: Warren Buffett himself, as recounted in Alice Schroeder’s terrific biography, The Snowball (pages 230-232).

Early in his career, Buffett invested heavily—almost one third of his early fund’s capital—in Sanborn Map, a company that mapped utility lines and such. But he soon grew frustrated with the company’s leadership, which “operated more like a club than a business,” and which refused to return greater dividends to investors. So Buffett amassed more and more stock, and with control of the company finally in hand he pressed the board of directors to split the company in two (one for the mapping business, and one to hold the company’s other outsized investments).

Finally, the board capitulated. But with victory finally at hand, Buffett nearly scuttled the deal because of … taxes. As Schroeder recounts, quoting Buffett, one director proposed that the company just cleanly break the company, despite the tax consequences—”let’s just swallow the tax,” he suggested.

To which Buffett replied (as he recounted to Schroeder): And I said, ‘Wait a minute. Let’s — “Let’s” is a contraction. It means “let us.” But who is this us? If everyone around the table wants to do it per capita, that’s fine, but if you want to do it in a ratio of shares owned, and you get ten shares’ worth of tax and I get twenty-four thousand shares’ worth, forget it.’

Buffett was willing to walk away from a deal because the taxes would have taken too much of a bite out of it.

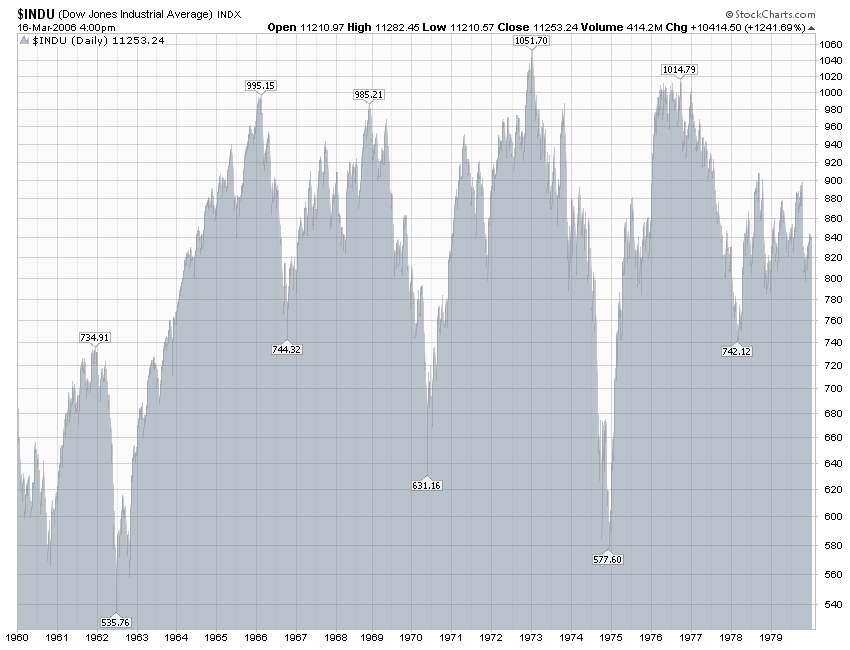

Between 1951 and 1954, when the capital gains rate was 25 percent and marginal rates on dividends reached 91 percent in extreme cases, I sold securities and did pretty well. In the years from 1956 to 1969, the top marginal rate fell modestly, but was still a lofty 70 percent — and the tax rate on capital gains inched up to 27.5 percent. I was managing funds for investors then. Never did anyone mention taxes as a reason to forgo an investment opportunity that I offered.

Under those burdensome rates, moreover, both employment and the gross domestic product (a measure of the nation’s economic output) increased at a rapid clip. The middle class and the rich alike gained ground.

So let’s forget about the rich and ultrarich going on strike and stuffing their ample funds under their mattresses if — gasp — capital gains rates and ordinary income rates are increased. The ultrarich, including me, will forever pursue investment opportunities.

That’s not the only time that taxes played a major role on Buffett’s decisions, as recounted by Schroeder. Later in the book (pp. 533-534), she recounts how Buffett chose to structure his investments under Berkshire Hathaway’s corporate umbrella, rather than as part of his hedge fund’s general portfolio, precisely because of the tax advantages.

In fact, as he explained in his 1986 letter to investors, changes in the 1986 tax reform act posed a specific threat to certain investment decisions:

If Berkshire, for example, were to be liquidated – which it most certainly won’t be — shareholders would, under the new law, receive far less from the sales of our properties than they would have if the properties had been sold in the past, assuming identical prices in each sale. Though this outcome is theoretical in our case, the change in the law will very materially affect many companies. Therefore, it also affects our evaluations of prospective investments. Take, for example, producing oil and gas businesses, selected media companies, real estate companies, etc. that might wish to sell out. The values that their shareholders can realize are likely to be significantly reduced simply because the General Utilities Doctrine has been repealed – though the companies’ operating economics will not have changed adversely at all. My impression is that this important change in the law has not yet been fully comprehended by either investors or managers.

And, wow, do we have plenty to invest. The Forbes 400, the wealthiest individuals in America, hit a new group record for wealth this year: $1.7 trillion. That’s more than five times the $300 billion total in 1992. In recent years, my gang has been leaving the middle class in the dust.

A huge tail wind from tax cuts has pushed us along. In 1992, the tax paid by the 400 highest incomes in the United States (a different universe from the Forbes list) averaged 26.4 percent of adjusted gross income. In 2009, the most recent year reported, the rate was 19.9 percent. It’s nice to have friends in high places.

The group’s average income in 2009 was $202 million — which works out to a “wage” of $97,000 per hour, based on a 40-hour workweek. (I’m assuming they’re paid during lunch hours.) Yet more than a quarter of these ultrawealthy paid less than 15 percent of their take in combined federal income and payroll taxes. Half of this crew paid less than 20 percent. And — brace yourself — a few actually paid nothing.

This outrage points to the necessity for more than a simple revision in upper-end tax rates, though that’s the place to start. I support President Obama’s proposal to eliminate the Bush tax cuts for high-income taxpayers. However, I prefer a cutoff point somewhat above $250,000 — maybe $500,000 or so.

Additionally, we need Congress, right now, to enact a minimum tax on high incomes. I would suggest 30 percent of taxable income between $1 million and $10 million, and 35 percent on amounts above that. A plain and simple rule like that will block the efforts of lobbyists, lawyers and contribution-hungry legislators to keep the ultrarich paying rates well below those incurred by people with income just a tiny fraction of ours. Only a minimum tax on very high incomes will prevent the stated tax rate from being eviscerated by these warriors for the wealthy.

Above all, we should not postpone these changes in the name of “reforming” the tax code. True, changes are badly needed. We need to get rid of arrangements like “carried interest” that enable income from labor to be magically converted into capital gains. And it’s sickening that a Cayman Islands mail drop can be central to tax maneuvering by wealthy individuals and corporations.

But the reform of such complexities should not promote delay in our correcting simple and expensive inequities. We can’t let those who want to protect the privileged get away with insisting that we do nothing until we can do everything.

Our government’s goal should be to bring in revenues of 18.5 percent of G.D.P. and spend about 21 percent of G.D.P. — levels that have been attained over extended periods in the past and can clearly be reached again. As the math makes clear, this won’t stem our budget deficits; in fact, it will continue them. But assuming even conservative projections about inflation and economic growth, this ratio of revenue to spending will keep America’s debt stable in relation to the country’s economic output.

In the last fiscal year, we were far away from this fiscal balance — bringing in 15.5 percent of G.D.P. in revenue and spending 22.4 percent. Correcting our course will require major concessions by both Republicans and Democrats.

All of America is waiting for Congress to offer a realistic and concrete plan for getting back to this fiscally sound path. Nothing less is acceptable.

In the meantime, maybe you’ll run into someone with a terrific investment idea, who won’t go forward with it because of the tax he would owe when it succeeds. Send him my way. Let me unburden him.

Warren E. Buffett is the chairman and chief executive of Berkshire Hathaway.

—

Norquist hits back against Buffett op-ed, calls argument ‘silly’

By Daniel Strauss – 11/26/12 06:12 PM ET

Americans for Tax Reform President Grover Norquist responded to an op-ed by billionaire Warren Buffett Monday, saying Buffett’s argument was “silly.”

On Monday The New York Times published an op-ed by Buffett criticizing Norquist’s anti-tax pledge and urging Congress to pass legislation rolling back the Bush-era tax rates for incomes above $500,000 a year. Later on Monday Norquist appeared on Fox News and called Buffett’s argument silly, and said Buffett got rich by “gaming the system.”

“Warren Buffett has made a lot of money, some of it off of gaming the political system. He invests in insurance companies and then lobbies to raise the death tax, which drives people to buy insurance. You can get rich playing that game but it’s all corrupt,” Norquist said. “It’s not investing; it’s playing crony politics and economics. That’s a shame. He’s done the same thing with some green investing. Shame on him for gaming the system and giving money to politicians who write rules that make your assets go up.

“The real economy, the real economy, if he thinks that the government can take a dollar and then you go to an investor who doesn’t have that dollar and it doesn’t affect investment, I’m sorry that’s just silly unless he plans on going to Obama and getting money from a stimulus package and he considers that investment. When the government takes a dollar away from the American people or a trillion dollars, that’s a trillion dollars not available to be saved and invested. I’m sorry if Buffett can’t see that but that’s kind of silly on his part.”

The back-and-forth between Norquist and Buffett comes as legislators seek to come to an agreement on a deficit-reduction package to avoid the “fiscal cliff” of spending cuts and tax increases set to hit next year.

A number of Republicans have indicated that they could disregard supporting the Americans for Tax Reform pledge in order to reach a deal.

Buffett, an outspoken supporter of President Obama, published an op-ed in the Times in 2011 arguing that the tax rates on the wealthiest Americans should be higher. The Obama administration subsequently began pushing for a “Buffett Rule” that would raise the marginal tax rate for some of the wealthiest Americans. Obama has since called for increasing the tax rate on incomes above $250,000 a year. The Buffett Rule also introduces a base 30 percent tax rate for incomes between $1 million and $10 million and a 35 percent rate for incomes over $10 million.

Source: http://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/269435-norquist-calls-buffet-argument-silly-

WHAT DO YOU, THE READERS, THINK?