http://fundooprofessor.wordpress.com/2012/07/09/flirting-with-floats-part-i/

The above blog is written by a finance professor and professional value investor. A great read.

http://fundooprofessor.wordpress.com/2012/07/09/flirting-with-floats-part-i/

The above blog is written by a finance professor and professional value investor. A great read.

The news speaks to both bull and bear market–but in a counterintuitive way. Here is a definition from Harold Ehrlich, who was with Shearson at the time and later became president and then chairman of Bernstein-Macaulay: “A bull market is when stocks don’t go down on bad news. A bear market is when stocks don’t go up on good news.”

Long cycle bottoms can be particularly hard to fathom. One famous story is that in the year 1938, when the stock market was still recovering from the crash of 1929 and had lurched along for years and years and years, essentially doing nothing, only three members of the graduating class of Harvard Business School went to work on Wall Street.

To bring this into a contemporary context (2012), my friend Dean LeBaron has said publicly, referring to the more than 100,000 members of the Financial Analysts Federation: “That’s too many analysts; by the time this is structural bar market is over, there will be only 50,000.” History thus suggest that by the time this structural bear market is all over, it may not be socially acceptable to be seeking a career on Wall Street. (Deemer on Technical Analysis by Walter Deemer)

Fairholme Stays the Course July 2012

Pzena’s 2nd Qtr. 2012 Letter:Pzena 2Q 2012

Editor: In my opinion, the edge you can gain in large-caps is in the behavioral area based on what embedded expectations are in the current market price rather than expecting an informati0nal edge. What gain can you have in understanding Coke’s operations in 150 different countries and several divisions rather than determining if you believe the market is too pessimistic or optimistic based on current prices?

Note the differences in expectations between the price of Coke in 1998 vs. 2009 or 2012. KO_VL.

A thorough discussion of the risks in Chinese stocks (investing outside your circle of competence):MW_EDU_071812_Sell Short

Use your gifts: Video http://www.foxbusiness.com/personal-finance/2012/07/18/all-have-gifts-but-question-is-are-using-them/?link=mktw

A research firm for assessing your aptitudes (natural gifts) is http://www.jocrf.org/

Herd mentality video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xU0cq3UvLaM

Barton Biggs (R.I.P.): http://www.thestreet.com/story/11618931/1/kass-rest-in-peace-barton-biggs.html

Chart Book: http://blog.haysadvisory.com/ (click on JP Morgan link for charts)

http://www.thestreet.com/story/11616900/2/melvin-the-art-of-being-cheap.html

Melvin: The Art of Being Cheap

By Tim Melvin07/14/12 – 06:00 AM EDT Real Money

Last week, a reader chided me for having an overly simplistic approach to investing. He pointed out, quite correctly, that the old Wall Street mantra of buying and holding quality stocks has not worked for investors for nearly a decade. Those who took it on faith have taken dramatic hits to their net worth.

My approach is not buy-and-hold as traditionally defined. I do not blindly buy or sell anything. I really do try to exercise the discipline to buy what is cheap and sell what is dear. I focus on valuation first — always. I use tangible book value as my chief measure of value but I also calculate intrinsic value and liquidation value for certain situations. I also do comps on takeover and merger situations by industry group to keep a constant measure of what rationale buyers are paying for companies similar to those I own. When a stock I own trades at a significant premium to its underlying value, I sell it regardless of market conditions. If the fundamentals change materially for the worse, I sell the stock. My approach is to buy what is cheap and sell what is expensive.

While it is a very simplistic strategy, that does not mean it is easy. Buying truly cheap stocks generally means you will be underinvested until the market undergoes a serious decline. You will be shopping in segments of the market that everyone hates and that attract negative commentary in the media. Your ideas will not be popular and will often be met with stunned disbelief. During those annual 10% declines and the meltdowns that occur every three years or so, your list of cheap stocks will be long and opportunities will be plentiful.

When everyone loves a stock and your nephew with the 600 SAT scores is racking up triple-digit returns by day trading, your stocks will be overvalued and there will no new opportunities. You will be selling stocks and holding a lot of cash. Even the most disciplined of us will start questioning our process when the hot stocks are jumping several points a day. I have seen the same cycle many times over my career. It always ends the same way: After a significant inventory creation event, stocks become cheap enough that I am a busy buyer once again, and the nephew goes back to waiting tables.

So, you will find yourself completely out of step with conventional wisdom. Buying a stock such as Kelly Services (KELYA) right now when the economic outlook is somewhat dire takes backbone and discipline. You have to ignore the market and focus on the fact that it is cheap. Being underinvested when the talking heads are screaming “Buy!” is not always easy. Neither is reading piles of 10-Qs and 10-Ks to find quality cheap stocks with the potential to recover. Running endless credit tests on companies that appear cheap is not exactly fun for most of us.

Buying the few stocks that are “too cheap not to own” until the stock market stages a sharp decline to create inventory requires discipline and patience. Holding stocks that are cheap when all the news appears negative requires mental toughness and belief in your approach — try being long natural gas stocks and small banks over the past year. The news flow could have you questioning your sanity if you did hold to your belief in asset-based investing.

During my lifetime, owning “too cheap not to own” stocks and waiting for inventory creation events has been exceptionally profitable for those few investors who practice the art of being an owner of assets purchased on the cheap.

Cooperman’s discussion of a Great Capital Allocator, Henry Singleton of Teledyne:Teledyne and Henry Singleton a CS of a Great Capital Allocator

June 28 (Bloomberg) — Leon Cooperman, chief executive officer of hedge fund Omega Advisors Inc., talks about his investment strategy, stock picks and the outlook for global economies. The story is featured in the August issue of Bloomberg Markets magazine. (Source: Bloomberg)

“The market is very sick,” Cooperman says. That’s not necessarily bad news for Cooperman, 69, a blustery billionaire from the South Bronx who first made his name as a stock picker during 25 years as an analyst atGoldman Sachs Group Inc. (GS) “We have to take advantage,” he says. “What’s ridiculously priced now?”

Omega, which currently invests its $6 billion in assets mainly in U.S. stocks, has returned an average of 13.3 percent annually since Cooperman founded it in 1991, compared with 11.4 percent for other equity-oriented funds, according to Chicago- based Hedge Fund Research Inc., Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its August issue.

For more than 40 years, Cooperman has earned a reputation for consistently ferreting out the most-discounted stocks — no matter what the overall market conditions.

“He’s not doing anything terribly fancy; he’s looking for stocks that are undervalued,” says Robert S. Salomon Jr., 75, an Omega client whose grandfather co-founded Salomon Brothers. “He’s had some great success in finding them.” Adds John Whitehead, 90, who was co-chairman of Goldman during Cooperman’s time there, “He’s been around a long time and seen bad markets and good markets, and he’s survived them all successfully.”

Markets on this particular day in May are being buffeted by fears about the future of the euro region, the possibility of U.S. tax cuts expiring at the end of 2012 and slowing growth in China. After the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index tumbled 6 percent in May, some money managers bet that the market would fall further. John Burbank, who runs the $3.4 billion Passport Capital LLC hedge fund, told Bloomberg News that he’s shorting stocks because he expects the U.S. and much of the rest of the world to fall back into a recession.

Cooperman is more sanguine about the future. As of June 11, his fund was up 6 percent this year–compared with 1.03 percent for hedge funds globally. He says stocks offer the best opportunities for investors, particularly in the U.S., where there are no signs of a recession. Banks are more profitable, household debt has declined and companies are increasing capital spending.

Yet stocks have remained undervalued, he says, because of economic troubles and uncertainty over the U.S. presidential election. TheS&P 500 (SPX) is trading at a price-earnings ratio of 12.5 compared with an average of 15 during the past 50 years.

“Stocks are the best house in the financial asset neighborhood,” Cooperman says, before adding a caveat: “It’s not clear whether it’s a good neighborhood or a bad neighborhood.”

Filling a large room in Cooperman’s investing house today is student loan providerSLM Corp. (SLM), better known asSallie Mae. With total educational debt in the U.S. ballooning to $904 billion as of March 31 from $241 billion a decade earlier, according to theFederal Reserve Bank of New York, some commentators have talked about a looming student-debt crisis.

Cooperman sees an opportunity. Sallie Mae throws off lots of cash, he says. Some 80 percent of its loans outstanding consist of government-backed debt issued before 2010, when Congress mandated that the government make certain college loans directly rather than subcontracting them to Sallie Mae. Since then, Sallie Mae has been expanding its private lending business, charging free-market rates that can run as high as 12.88 percent.

Cooperman started buying Sallie Mae in December 2007, after a $25 billion buyout deal with J.C. Flowers & Co.,JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM) andBank of America Corp. collapsed amid the credit crisis, sending its shares plummeting. On April 21, 2011, the company announced that it would reinstate its dividend, sending the shares up 13 percent to $16.13. Cooperman paid an average of $7.36. SLM closed at $15.20 on Wednesday, and Omega predicts that it will rise as high as $22. Omega is the eighth-largest owner of the company, with a 3.51 percent stake.

“Ultimately, it’ll work,” Cooperman says of SLM. “Lots of kids have to borrow money; their parents have to cosign the loans. It’s a profitable business.”

Not all of his bets work out. Omega had considered JPMorgan Chief Executive OfficerJamie Dimon the best in the industry, and the bank’s management had been aggressively repurchasing stock. Omega started buying shares of the New York bank in 2009 at an average cost of $37.14.

JPMorgan disclosed on May 10 that it had a $2 billion trading loss because of riskier-than-expected credit securities. Omega sold about two-thirds of its position the next day, taking a loss: The shares tumbled 9 percent on May 11, closing at $36.96. They traded at $36.78 yesterday.

At Omega’s staff meeting in May, one of the portfolio managers suggests that JPMorgan shares may now be ridiculously cheap. Cooperman launches into a tirade about how Dimon has been unfairly pilloried by Representative Barney Frank and other critics. “I’m incensed by some of the sh– you’re reading,” Cooperman tells his managers. He says he’ll hold on to his remaining shares as a vote of confidence in Dimon. Cooperman, a self-described workaholic, says there’s no magic formula to finding good stocks.

Cooperman expects stocks to return 7 to 8 percent in the future, below their historic 10 percent returns.

Barry Rosenstein, co-founder of the $3 billion Jana Partners LLC hedge fund in New York, admires Cooperman’s work ethic. Rosenstein was a teenager when he first met the fund manager at a sailing club on the Jersey Shore of which both were members. Cooperman would show up with a stack of annual reports, disappear onto his boat and read them all weekend, Rosenstein, 53, recalls.

“If Bruce Springsteen is the hardest-working man in rock ’n’ roll, Lee is the hardest-working man in the investment business,” he says. Cooperman was one of the first to invest in Jana when Rosenstein founded it in 2001.

As he scours reports and quizzes executives on earnings calls and at conferences, Cooperman is trying to discover stocks that have a low price-earnings ratio, lots of cash and decent yields and that are trading for less than their net assets are worth. He also looks for what he calls smart managers who own big stakes in their companies and for firms that buy back their own shares cheaply.

While he was at Goldman, one such hit was what’s now called Teledyne Technologies Inc. (TDY), whose founder, Henry Singleton, made acquisitions using the company’s stock when its price was high. When the share price went down, Singleton bought back shares repeatedly. Under Singleton, Teledyne expanded its defense, aerospace and industrial businesses. Cooperman recommended the stock in 1968, and for the following two decades, it generated a 23 percent annual return. Cooperman displays a framed 1982 letter in his office fromWarren Buffett congratulating him on his analysis of Teledyne.

One of Cooperman’s largest holdings today is Apple Inc. (AAPL), which Omega portfolio manager Barry Stewart says he likes because of its $110 billion cash hoard. Apple’s prospects for growth are strong, he says, with the market booming for its iPhone smartphones, MacBook computers and iPad tablets.

Cooperman pounced on the stock at an average of $376 a share starting in July 2010, around the timeConsumer Reports said a faulty iPhone 4 antenna could cause the phone to lose its signal. The problem proved to be a hiccup, and Apple shares have since risen to $574.60. Stewart projects that the stock will go as high as $710 in the next year.

Stewart is also betting that growing demand for 3G and 4G mobile phones made by Apple and others such as Samsung Electronics Co. will boost the fortunes ofQualcomm Inc. (QCOM), the largest producer of semiconductor chips for the devices. Omega began buying Qualcomm last August at an average price of $53. The shares traded at $54.91 on Wednesday, and Stewart says they could rise as high as $85 in the next 12 months.

One of Cooperman’s worst-performing holdings this year is McMoRan Exploration Co. (MMR), an oil-and-gas drilling company whose price plunged about 40 percent from a high of $14.55 on Dec. 30 after an equipment malfunction caused delays at one of its wells in the Gulf of Mexico. Cooperman is still enthusiastic about its prospects because it meets his requirement of smart management.

James “Jim Bob” Moffett, the New Orleans-based company’s CEO, is also chairman ofFreeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. (FCX), the world’s largest publicly traded copper producer, and has a track record of making deals in far-flung places. McMoRan formed a joint venture with Chevron Corp. (CVX) to drill for oil in Louisiana. Omega paid $10 on average for the shares, which traded at $12.30 on Wednesday. If the company strikes oil, Omega predicts that the stock could reach $25 to $30 within 18 months.

When a company considers its own stock a bargain, Cooperman wants in too. That was the case withAmerican International Group Inc. (AIG), the New York-based insurer majority owned by the U.S. government after its 2008 bailout. CEO Robert Benmosche has bought back shares from the U.S. Treasury and repaid funds tied to AIG’s government bailout.

When a company considers its own stock a bargain, Cooperman wants in too. That was the case withAmerican International Group Inc. (AIG), the New York-based insurer majority owned by the U.S. government after its 2008 bailout. CEO Robert Benmosche has bought back shares from the U.S. Treasury and repaid funds tied to AIG’s government bailout.

The company bought $3 billion of its stock in March, and $15 billion of planned asset sales should fuel more buybacks, Omega portfolio manager Mahmood Reza says. Omega bought the shares this year for an average of $30.47 and anticipates that the price could rise to $53 by the end of 2013. They traded at $30.82 on Wednesday.

Cooperman also hunts for takeover candidates. Omega zeroed in on Charming Shoppes Inc., the owner of plus-size-clothing retailer Lane Bryant, after visiting the company’s executives. The company’s cash exceeded debt and had the potential for higher profitability as part of a bigger group.

He started buying the shares at less than $3 each last year and added to his position after David Jaffe, CEO ofAscena Retail Group Inc. (ASNA), formerly known as Dress Barn Inc., told a conference that he was interested in buying companies. Omega amassed a 13 percent stake in Charming Shoppes. In May of this year, Ascena agreed to buy the company for $7.35 a share.

In 1998, Cooperman bet big on emerging markets — and lost. The misstep was compounded by Omega’s investment of more than $100 million with Czech financierViktor Kozeny in a plan to take over Azerbaijan’s state oil company. New York state prosecutors accuse Kozeny, who now lives in the Bahamas, of stealing Cooperman’s investment, while U.S. prosecutors say Kozeny led a multibillion-dollar bribery scheme in connection with the Azeri deal.

In 2007, Omega paid $500,000 to the U.S. to resolve the – bribery investigation. Omega didn’t admit wrongdoing while it accepted legal responsibility for the actions of an employee who admitted joining Kozeny’s bribery scheme. Kozeny denies wrongdoing.

In all, Omega lost a total of $500 million, or 13 percent of its total assets in 1998, after which Cooperman fired almost the entire emerging-markets team. (He later recovered some of the money.) He says the episode was the worst chapter of his life.

The younger of two sons of Polish immigrants, Cooperman bagged fruit and changed tires to make money as a teenager in the Bronx. He learned how to analyze securities from the late Roger Murray, a professor at Columbia Business School. Another professor’s recommendation earned Cooperman a job as a research analyst at Goldman.

Cooperman’s office is filled with mementos of his years at Goldman, for which he still manages an undisclosed amount of money. A framed copy of the company’s business principles is displayed in Cooperman’s office, near a curled-up whip — a gift from Goldman salesmen after he completed a 30-city, 20-day roadshow to market a stock fund in 1990. After years in research, Cooperman founded Goldman Sachs Asset Management in 1989.

Despite being a billionaire, Cooperman, who has three grandchildren, says he has no plans to retire soon. “He’s the first one in the office, the last one out,” says Tomas Arlia, head of hedge funds at GE Asset Management Inc., which has had money with Omega since its inception. “He loves what he does.”

A piece of paper taped to his computer monitor reminds Cooperman of the simple investing rules that have helped Omega weather market storms for the past two decades: “Buy low, sell high, cut your losses, let your profits run.”

Posted in Investing Careers, Investing Gurus

Tagged Cooperman, Henry Singleton, Teledyne, work ethic

Can anyone point out several omissions and/or fallacies in this article by the famous professor Richard Thaler? Just a sentence or two.

Prize to be emailed. (Hint: biggest bubble today)

By RICHARD H. THALER

IMAGINE a set of 65-year-old identical twins who plan to retire this summer after long careers. We’ll call them Dave and Ron. They have worked for different employers and have accumulated retirement benefits worth the same amount in dollars, but the benefits won’t be paid out the same way.

Dave can count on a traditional pension, paying $4,000 a month for the rest of his life. Ron, on the other hand, will receive his benefits in a lump sum that he must manage himself. Ron has a lot of choices, but all have consequences. For example, he could put the money into a conservative bond portfolio and by spending the interest and drawing down the principal he could also spend $4,000 a month. If Ron does that, though, he can expect to run out of money sometime around the age of 85, which the actuarial tables tell him he has a 30 percent chance of reaching. Or he could draw down only $3,000 a month. He wouldn’t have as much to live on each month, but his money should last until he reached 100.

Who is likely to be happier right now? Dave or Ron?

If this question seems a no-brainer, welcome to the club. Nearly everyone seems to prefer the certainty of Dave’s pension to Ron’s complex options.

But here’s the rub: Although people like Dave who have them tend to love them, old-fashioned “defined benefit” pensions are a vanishing breed. On the other hand, people like Ron — with defined-contribution plans like 401(k)s — can transform their uncertainty into a guaranteed monthly income stream that mirrors the payouts of a traditional pension plan. They can do so by buying an annuity — but when offered the chance, nearly everyone declines.

Economists call this the “annuity puzzle.” Using standard assumptions, economists have shown that buyers of annuities are assured more annual income for the rest of their lives, compared with people who self-manage their portfolios. One reason is that those who buy annuities and die early end up subsidizing those who die later.

So, why don’t more people buy annuities with their 401(k) dollars?

Here’s one part of the answer: Some people think that buying an annuity is in some way a bad deal for their heirs. But that need not be true. First of all, a retiree can decide to set aside some portion of a retirement nest egg for bequests, either immediately or at a later date. Second, if a retiree chooses to manage his or her own money, the heirs may face the following possibilities: Either they get financially “lucky” and the parent dies young, leaving a bequest, or they are financially “unlucky,” meaning that the parent lives a long life, and the heirs take on the burden of support. If you have aging parents, you might ask yourself how much you’d be willing to pay to insure that you will never have to figure out how to explain to your spouse, or whomever you may be living with, that your mother is moving in.

There are other explanations for the unpopularity of annuities, but I think two are especially important. The first is that buying one can be scary and complicated. Workers have become accustomed to having their employers narrow their set of choices to a manageable few, whether in their 401(k) plans or in their choice of health and life insurance providers. By contrast, very few 401(k)’s offer a specific annuity option that has been blessed by the company’s human resources department. Shopping for an annuity with hundreds of thousands of dollars at stake can be daunting, even for an economist.

The second problem is more psychological. Rather than viewing an annuity as providing insurance in the event that one lives past 85 or 90, most people seem to consider buying an annuity as a gamble, in which one has to live a certain number of years just to break even. But, as the example of Dave and Ron shows, it’s is the decision to self-manage your retirement wealth that is the risky one.

The most complex and unknowable part of that risk is in predicting how long you will live. Even if there are no medical advances in the coming years, according to the Social Security Administration, a man turning 65 now has almost a 20 percent chance of living to 90, and a woman at this age has nearly a one-third chance. This means that a husband who retires when his wife is 65 ought to include in his plans a one-third chance that his wife will live for 25 more years. (A “joint and survivor” annuity that pays until both members of a couple die is the only way I know for those who are not wealthy to confidently solve this problem.)

An annuity can also help people with another important decision: when to retire. It’s hard to have any idea of how much money is enough to finance an appropriate lifestyle in retirement. But if a lump sum is translated into a monthly income, it’s much easier to determine whether you have enough put away to afford to stop working. If you decide, for example, that you can get by on 70 percent of preretirement income, you can just keep working until you have accrued that level of benefits.

IN the absence of annuities, there is reason to worry that many workers are having trouble with this decision. Over the last 60 years, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the average age at which Americans retire has trended downward by more than five years, from 66.9 to 61.6. Of course, there is nothing wrong with choosing to retire a bit earlier, but over the same period, live expectancy has risen by four years and will likely continue to climb, meaning that retirees have to fund at least an additional nine years of retirement. Those who manage their own retirement assets can only hope that they have saved enough.

Annuities may make some of these issues easier to solve, but few Americans actually choose to buy them. Whether the cause is a possibly rational fear of the viability of insurance companies, or misconceptions about whether annuities increase rather than decrease risk, the market hasn’t figured out how to sell these products successfully. Might there be a role for government? Tune in next time for some thoughts on that question.

Richard H. Thaler is a professor of economics and behavioral science at the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago. He is also an academic adviser to the Allianz Global Investors Center for Behavioral Finance, a part of Allianz, which sells financial products including annuities. The company was not consulted for this column.

Re “Annuities and the Puzzle of Income” (Economic View, June 5), in which Richard H. Thaler described some advantages of buying annuities:

Annuities are superficially attractive, but they have important flaws the column did not discuss. People don’t tend to buy diversified sets of annuities, and because they are issued by inherently leveraged financial intermediaries, there can be material credit risks that are hard to assess over the 20- to- 40-year horizon of their payouts.

Annuity providers also incur sales charges and operating expenses, and need capital and a cushion of economic earnings. Those costs may not be incurred by someone making their own investments, or doing so through lower-cost vehicles.

Finally, inflation is an even more important consideration. Not discussing it is like playing “Hamlet” without the prince. In 30 years, the level of consumer prices in the United States might double or sextuple. The first would be painful, and the second ruinous, to someone who relied only on a fixed annuity.

Paul J. Isaac

Manhattan, June 5

The writer is the portfolio manager at Arbiter Partners, a hedge fund.

Editor:A devastating critique of annuities: Credit risk, high costs, and inflation risk. Right now might be the WORST TIME in the past 100 years to buy an annuity. Be careful out there in your search for returns.

For those who gave a good answer, claim your prize. This link will disappear in a day and the prize will go into the Value Vault (under spins). Remember just email me at aldridge56@aol.com with VALUE VAULT in the subject line (don’t write anything else). The value vault has over 200 books, videos, case studies and just plain great material for learning about investing and business analysis. Reward given ($$$) to someone who can find a better resource on the web.

Posted in Economics & Politics, Investing Gurus

Tagged annuities, Behavioural economics, richard thaler

Entrepreneurs making a new market!

http://www.designs.valueinvestorinsight.com/bonus/bonuscontent/docs/CentaurProcess.pdf

http://www.hedgefundletters.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/CVF-One-Page-Summary-July-2010.pdf

We have long been devoted to the practice of maintaining written research on each of our Fund’s investment ideas as a way to document our thoughts and expectations for each idea. Generally, our research should explain why a given investment should work, the risks that might keep it from working, and define a range of plausible scenarios that we use to formulate our valuation assumptions.

As ideas play out, we document the interim events and any decisions we make along the way. If an investment doesn’t work out, we try to determine whether there is a lesson to be learned that will benefit us in our future decisions.

While this research process is time-consuming, over the years we have come to believe in the approach even though there can be periods where the process doesn’t seem like it is helping our performance. Even worse, we occasionally succumb to mistakes that we should have recognized from prior experience, usually after sufficient time has passed to take the sting out of the prior event. Recently, however, we encountered a situation where we did benefit from having documented our experience with a similar investment many years ago.

Betting on the Jockey Rather than the Horse

As part of our search for promising investments, we look for management teams with great long term track records and that are strongly aligned with common shareholders. Over time, however, we have learned that so-called “jockey” investments can be a form of a value trap in certain conditions. Often, the reputation and track record of a manager or team can overshadow the quality and value of the underlying business. An investment based on faith that a given management will create value without careful analysis of the assets in place can be dangerous, and such stocks are prone to a “halo effect” that lasts until something goes wrong. It is easy as investors to become infatuated with a great management team to the extent that one might be willing to buy a stock without being entirely sure of getting great value for the underlying business. It is therefore quite common for businesses with well-known and well-regarded management to trade for a significant premium to comparable peers.

What we’ve learned is that while we very much prefer to have great “jockeys” directing our investment horses, it is usually a mistake to pay a premium for the privilege. It is usually far better to patiently wait until the stock gets cheap enough to eliminate any management premium. By not paying extra for management, we protect ourselves from the same types of errors in judgment that can occur when assessing business quality or business valuation. When the management team either turns out not to be as good as hoped or alternatively where good management simply makes what turns out to be a mistake that impairs investment value, capital is protected to some degree by ensuring that we do not overpay for the underlying assets or business.

Back in 2006, we decided to make an exception to the above rule of buying the assets at a discount and getting the management for free. The stock was Sears Holdings, and the “jockey” was Edward Lampert.

At the time, we wrote an internal research document arguing that Lampert’s track record was so good that we should purchase Sears Holdings even though we couldn’t make a strong and convincing case that the stock was undervalued. Rather, we made the case that the risk of missing out on the potential benefits of such an obviously great manager in his prime would be the greater sin. In essence, we were willing to pay up for value that hadn’t yet been created because we were so sure it would be. We realized our mistake a year or so later and sold the stock. We never had any real idea what Sears Holdings was worth, and we still don’t.

(CSInvesting: an honest, brave assessment of a permanent loss of capital)

Recently we were struggling with the temptation to invest in a new idea featuring many of the same ingredients: a management team with impressive credentials that is highly incentivized to create value for shareholders taking over a business that has been performing poorly relative to peers, making it ripe for a management turnaround. The stock was JC Penney, which was trading for about $35 at the time of our initial analysis.

After working through several iterations of the potential valuation case, we still couldn’t come up with a clear picture of what the business is worth with any high level of conviction. Still, the idea seemed to pull at us, until we asked ourselves a simple question: if this idea doesn’t work out, is there an obvious mistake that we will be able to point to and kick ourselves for having made? The answer was yes – that we would be making the Sears Holdings “jockey” mistake. We decided against the investment.

In any event, JCP now trades at a much lower price than when we first looked at it, and the market no longer views the management through the same rose-colored lenses it did even three months ago. While we still have a very high regard for the management team at JCP, we haven’t been able to get any more comfortable with our ability to value the business. So even at the much lower price, JC Penney is not an easy call for us.

While we won’t be surprised to see JC Penney work out as an investment – particularly from the recent $20 price – we simply have been unable to get to the point where we have great conviction in the idea. Until we do, we will leave it to others who may understand it better — and we won’t kick ourselves if it turns out to be a money maker for someone else. We are grateful, however, for the benefit of having documented a mistake we made back in 2006 so that we did not repeat it in 2012.

http://seekingalpha.com/article/598621-sell-j-c-penney-too-much-change-too-soon?source=kizur

CSInvesting: This is an example of how you can learn from your investing experience. The author recorded his investment, then honestly assessed how it developed and used what he learned to avoid a future loss.

Posted in Investing Gurus, YOU

Tagged business, Centaur Value, JCP, plausible scenarios, SHLD

Information Overload

Columbia business student to Richard Pzena of Pzena Investment (www.pzena.com) why do you think there will be value opportunities with so much more available information?

Pzena, “Because of this…as he slaps a 700-page 10-K on a desk in front of his lecturn. Nobody reads these because there is too much information. You must know what to look for.

Ben Graham meets Mises

Lessons and Ideas from Benjamin Graham by Jason Zweig:Lessons-Ideas-Benjamin-Graham_Zweig_AIMR

Value Investing from a Austrian Perspective, A paper on Ben Graham and Mises: http://mises.org/journals/scholar/Leithner.pdf

February 28, 2004 by Robert Blumen

Monday, July 11, 2011 at 8:45PM

Today we had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Chris Leithner. He has lived in Australia for the last twenty years and is the author of The Evil Princes of Martin Place. The book delineates the evils of all central banks and has some unique perspectives on Australia’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

We took this opportunity to ask Chris about his thoughts on central banking, investing and his views on the RBA, the Australian dollar and Australian stocks.

The Dollar Vigilante (TDV): Thanks for taking the time to speak with us, Chris. To begin, give us some background on yourself.

Chris LeithnerChris Leithner (CL): Sure, I came to Australia from Canada in 1987, in order to take a postgraduate degree. After a few years of further study in the UK, I returned to Oz in 1991. After a couple of years, I became a jaded academic; and after a few more I became an ex-academic. I learnt that the adage “those who can, do; and those who can’t, teach” has more than a ring of truth to it. Partly for that reason, and also because in the 1990s I also discovered Austrian School economics, Ben Graham and their commonalities, in 1999 I formed Leithner & Company (http://www.leithner.com.au). It’s a private investment company, based in Brisbane, which adheres strictly to the “value” approach to investment pioneered by Graham and to the economic insights of Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard.

Chris LeithnerChris Leithner (CL): Sure, I came to Australia from Canada in 1987, in order to take a postgraduate degree. After a few years of further study in the UK, I returned to Oz in 1991. After a couple of years, I became a jaded academic; and after a few more I became an ex-academic. I learnt that the adage “those who can, do; and those who can’t, teach” has more than a ring of truth to it. Partly for that reason, and also because in the 1990s I also discovered Austrian School economics, Ben Graham and their commonalities, in 1999 I formed Leithner & Company (http://www.leithner.com.au). It’s a private investment company, based in Brisbane, which adheres strictly to the “value” approach to investment pioneered by Graham and to the economic insights of Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard.

TDV: How did you first get exposed to Austrian economics?

CL: Increasingly repelled by the absurdities and outright falsehoods of the economic and financial mainstream, I found Austrian Economics in exactly the way that the Austrian School shows how so many things happen: by accident rather than by design. I found it almost everywhere except at university; and as I think back, the more of it that I found, the more repugnant academic life became. I read Mises, Rothbard and others on capital, value, interest rates and the business cycle. I also read Lionel Robbins, The Great Depression (1934) and Wilhelm Röpke, Crises and Cycles (1936). Although Robbins later disavowed Austrian methods and insights, I realised that both he and Röpke provided clear and forceful expositions of the mechanics of the Austrian interest-rate and business-cycle model. Amazingly, within a couple of years of the Great Depression’s nadir, they published more theoretically and empirically rigorous accounts than (for example) Ben Bernanke’s Essays on the Great Depression, Princeton University Press, 2004.

Not only has the mainstream learnt nothing since the 1930s: it has unlearnt what’s worth knowing!

TDV: Yes, it’s not what they don’t know but it is what they know that just ain’t so. So, why did you write The Evil Princes of Martin Place?

CL: I sought to demonstrate to an audience of interested laypeople, both in Australia and other countries, that there’s little new under the sun: the “Global Financial Crisis,” as the events of 2007-2009 are commonly known in Australia, is merely the latest in a long series of economic and financial crises that have punctuated the history of the past 250 or so years. Like its predecessors, three of which (namely the Panic of 1907, the Depression of 1920-1921 and the Great Depression of 1929-1946) the book analyses in detail, interventionist policies – in particular, legal tender laws, fractional reserve banking and central banking – are the GFC’s ultimate causes. Accordingly, only when we recognise that monetary central planning is the ultimate source of our financial and economic distemper, and when it either collapses or is consigned to the dustbin of history, and when 100%-reserve banking and sound money replace fractional reserve and central banking and fiat currency, will the ruinous cycle of boom and bust become as thing of the past.

TDV: Tell our audience generally what the book is about

CL: Sure, Part I (Chapters 1-5) uses basic logic and evidence to isolate the causes of the GFC, Panic of 1907, etc. It demonstrates, in short, that these crises are failures of government – and not of liberty. Following Herta de Soto, it demonstrates that deposits are not (and can never legitimately be) loans, that the history of fractional reserve banking is the history of bank crises and failures. Following Rothbard and Mises, it also shows how fractional reserve banks misappropriate and counterfeit.

Part II (Chaps. 6-9) analyses counterfeit money, the central bank and the welfare-warfare state. It demonstrates, following a long line of scholars, that fractional reserve banking is logically absurd, utterly fraudulent – and hence legally untenable. It also outlines the basic operations of central banking (e.g., open market operations, etc.). Conceiving the central bank as a monetary central planner, it also demonstrates (following Mises, who did it did for central planning generally) that monetary central planning inevitably fails. Finally, following Hoppe, who demonstrated in Democracy: The God That Failed (Transaction Books, 2002) that private property (i.e., individual ownership and rule) and democracy (i.e., collective ownership and majority rule) are incompatible, it outlines the invidious moral and ethical consequences (which it calls the “monetary roots of democratic pathologies”) of fractional reserve and central banking.

Part III (Chaps. 10-14) provides historical analyses of where we’ve been, where we are now and where we’re headed. It puts the Depression of 1920-21 and Great Depression into an Austrian context; so too with Australia’s “miracle economy” of 1991-2007 and the Commonwealth Government’s reaction to the GFC. It concludes that its reaction has merely set the stage for a later and bigger crisis.

Finally, Part IV (chaps 15-16) outlines where we should go – namely outlaw fractional reserve and central banking – and provides further reading for those who are interested.

TDV: We find all of your subject matter interesting but the main reason I wanted to interview you was to give the TDV audience some perspectives on what is going on in Australia right now. Tell us some of your thoughts about Australia’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia.

CL: Australians have become a bit cocky in recent years, to the point where “Australian Exceptionalism” or something akin to it swells many hearts; it’s not just The Lucky Country: to many people, it’s apparently The Country That Deserves to Be Lucky.

TDV: The same thing has been happening in Canada. It’s amazing what living in a place with some natural resources in the ground and a currency performing relatively well can do to puff out the chests of some people!

CL: Haha, yes. One of my intentions in The Evil Princes of Martin Place is to remind them that the laws of economics are universal across time and space – and therefore, that, just as fractional reserve and central banking inflated the booms that have burst in Europe and the U.S., so too they’ve inflated the booms that will bust in China and Australia.

TDV: Explain to us how the RBA is different, or similar, from the other central banks we are more familiar with like the Fed, BoE and BoJ

CL: For all practical purposes, it seems to me that central banks’ similarities (which The Evil Princes emphasises) are far more important than their differences. As an analogy, the Fierce Snake (Oxyuranus microlepidotus), Common Brown Snake (Pseudechis australis) and Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) are the world’s three most-venomous snakes. For all I know (I don’t), their diets, reproductive habits and habitats, among other things, differ. But what’s most relevant from my point of view is that each is very poisonous – and is an Australian native. Similarly, a mainstream economist might assert that over the past decade the RBA has targeted the CPI more formally than the Fed. Both, however, relentlessly undertake the open market ops that ignite the boom that eventually busts, and it’s that commonality that I try to keep uppermost in mind.

TDV: The Australian Dollar (AUD) has been on a wild ride the last few years… how do you explain this from your Austrian viewpoint and from what you know about the AUS central bank?

CL: Because Leithner & Co. invests almost exclusively in Australia and New Zealand, I’ve never thought about it. Well, that’s not quite true: the $A is a fiat currency; and as such, its purchasing power almost constantly falls. But I have no insight whether it will melt faster than the £, €, $US, etc. I suspect, but obviously don’t know, that taking short-term or even medium-term positions on the price of the $A vis-à-vis another currency is either a waste of time or a rod for one’s own back. Certainly I don’t know anybody who’s made a living – let along accumulated significant wealth – trading the $A or any other currency.

Your question prompts me to reflect that, when it comes to the currency, I am very Grahamite; that is, I concentrate on the micro (the security) rather than the macro. Your question also brings to mind Buffet’s observation in 1994: “If Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan were to whisper to me what his monetary policy was going to be over the next two years, it wouldn’t change one thing I do.” In effect, in 2009 Glenn Stevens, Ben Bernanke and all the sordid rest DID shout what their monetary policies were going to be, and it hasn’t changed either my approach to investment or my highly jaundiced attitude towards central bankers and central banking.

TDV: Give us an overview of the current political/central banking climate in AUS… what’s your thoughts? Should we be buying AUS stocks? AUD? Or selling?

CL: Well, let’s first take the mainstream’s prevailing attitude towards central banking in general and the RBA in particular: central planning rules! Not just in Oz, but in all Western countries (and Eastern ones, for all I know) the state has embedded its protections of fractional reserve and central banks so deeply within its legislation and regulations – in other words, it has extended such enormous privileges to these banks for such a long time – that virtually nobody now recognises bankers for what they have long been: massively featherbedded white-collar wharfies (for decades until a decade or so ago, longshoremen were the most notoriously protected, overpaid and arrogant workers in Australia). The events of the past couple of years have alerted the man in the street to the reality that something is rotten in Denmark — or, more precisely, Australian and other banks — but he can’t quite put his finger on it.

In Australia, economists, investors and journalists babble endlessly about the level at which the Reserve Bank should “set” the “official interest rate” (by which they mean the Overnight Cash Rate). Alas, almost nobody bothers to ask why it should be set, or whether it actually can be fixed. After all, the benchmark price of (say) wheat isn’t set: it’s discovered throughout the day at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Similarly, the spot price of copper is constantly discovered and rediscovered at the London Metals Exchange. More generally, the impersonal forces of supply and demand determine many prices. Yet, for reasons rarely discussed and never justified, virtually nobody baulks at the notion that a short-term money market rate of interest must be “set” by a committee of price-fixers and central planners in Martin Place, Sydney.

Hence, an inconvenient question: given that most “right thinking” people like mainstream economists and financiers (correctly) believe that the production of goods such as motor cars, frozen vegetables, etc., should occur within a régime of market competition, why do the Good and the Great insist – some of them quite vehemently – that “we” must exclude the production of money from market forces? Why, in an allegedly free society, must the government monopolise the definition of money? Why must its production and regulation be entrusted to a deified government monopolist called the central bank? Nobody in mainstream Australia is ever able to answer these questions; instead, they ridicule or simply ignore them.

Yet even to consider these questions is to grasp that the Global Financial Crisis is not a “market failure.” Rather – and in a way that parallels the collapse of Communist economies – the GFC is the inevitable consequence of the hubris of central planning. Communism epitomised general economic central planning, and it eventually collapsed. Central banking, whether in Australia, Britain, China or the U.S., is monetary central planning; as a result, it too will ultimately be consigned to the dustbin of history. From the repudiation of the gold clause and confiscation of gold in 1933 to the closing of the “gold window” in 1971, the chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, as well as his counterparts in the Reserve Bank of Australia, etc., have increasingly deprived market participants of market signals – that is, of real information in the form of unfettered rates of interest. In particular, market participants have been deprived of a key warning signal and great source of discipline (the right to exchange dollars for gold). Central bankers, in short, have caused credit markets to emit false signals; as a result, these markets don’t tell the truth about time.

TDV: We totally agree, of course. And also find it so bizarre that hardly anyone questions having communist style central planning embedded at the very heart of the so-called capitalist system. What is your take on Australian stocks?

CL: In Leithner & Co.’s current Newsletter to its shareholders, I note a paradox: those who didn’t see the GFC coming (and remained wilfully blind after it erupted) – the very people who incurred big losses in 2007-2009, which they’ve not recouped – today remain resolutely upbeat about the future. They were diametrically wrong then; why should anybody think they’re less wrong today?

In sharp contrast, the doughty few who anticipated trouble and who have consistently generated profits since 2007 remain downcast today. It’s demonstrably false to assert, as the mainstream has since 2007, that “nobody saw it coming.” What’s certainly true is that the few who foresaw the GFC and now see that we’re merely in the eye of the storm, were then and today remain, from a mainstream point of view, “nobodies.”

A second point is that in a Newsletter dated 26 June 2009, I posited assumptions and conducted an analysis that yielded nine estimates of the All Ordinaries Index’s “fair value.” If earnings fall to their long-term trend and bearish multiple emerges, then the All Ords’ fair value is 1,688 – roughly half the level of its low in March 2009 and one-third of its level (4,700) in early July 2011. If earnings remain constant and the “bullish” multiple suddenly prevails, then fair value is 5,512 – a modest 67% above the March 2009 trough. Mid-range assumptions with respect to both earnings and the multiple generate an estimate of 3,127 – just below the March low. Re-reading that analysis and considering its premises, I think its conclusions remain sound: Australian investors need to incorporate into their plans the possibility that Australian indexes fall by 50% or more.

A third point is that, recent decades in Australia, have not, in economic and financial terms – and as the Commonwealth Government, RBA and their sock-puppets in the media and universities strenuously insist – been truly stable. In The Evil Princes I noted that for seven decades Communism in the Soviet Union was apparently secure. But it was hardly durable, as its sudden and unexpected (to the Western mainstream) collapse demonstrated. I also show that since the early 1990s the much-vaunted “fundamentals” of the Australian economy have hardly – despite the mainstream’s ubiquitous and often strident insistence – been sound. Since 2007, it’s become obvious in Europe and the U.S. that the “stability” of the past few decades was – like the “strength” of the Soviet Union – apparent rather than real. The truth is that the long Australian boom since the early 1990s has not reflected the success of the mainstream’s interventionist policies. The ructions since 2007, however, have revealed the artificiality of the conditions these interventions created.

Alas, like the Bourbons of old, today’s politicians, central and fractional reserve bankers have forgotten nothing and learnt nothing from the financial and economic catastrophes they’ve repeatedly fomented – and thereby expose the rest of us to the next crisis. Unfortunately, the lesson of history seems to be that the politicians people admire most extravagantly are (like Franklin Roosevelt) the most audacious liars; conversely, the ones they erase from memory are, like Warren Harding, those who dare to tell them the truth.

Accordingly, since 2007 governments around the world have intervened massively and lied flagrantly. Their frenzied “fiscal stimulus” and hysterical “monetary stimulus” have ignored the lessons of the “Good Depression” of 1920-1921 and reprised many of the errors committed during the Great Depression of 1929-1946. Most notably, major central banks are presently moving heaven and earth to suppress market rates of interest; the appropriate course is to abandon the intervention and to let rates rise. Similarly, Western governments are increasing expenditure and incurring huge deficits; the correct policy, of course, is to slash spending, taxes and deficits, and to use the resultant surplus to retire debt. Since 2007, in short, central bankers and politicians – as much in Oz as in Europe, China and America – have been energetically inflating the next bubble and thereby stimulating the next crisis. My prognosis is therefore sombre.

TDV: We agree with you on that count as well. You certainly, more than 99.9% of money managers out there, really know what is going on thanks to your grasp of Austrian economics. For those interested, please let them know about how they can take advantage of your investment services.

CL: A short summary of our results since inception can be seen here, and an extended analysis of our results during the past decade and its strategy for the next ten years can be seen here.

Leithner & Co. accepts new investors. It caters primarily to professional and sophisticated investors as defined in sections 708(8) and 708(11) of the Australian Corporations Act. In plain English, that means investments of at least $A500,000. Also, because Leithner & Co. is a company and not a fund, its investors own shares in a private company rather than units in a unit trust (or what Americans would call a mutual fund). Unlike units, these shares are illiquid. So not just as a result of its investment philosophy, but also as a consequence of its structure, Leithner & Co. probably isn’t suitable for most people.

Learn more:http://www.leithner.com.au/archives.htm

Another Investor who combines his value investing philosophy with Austrian economics: http://www.bestinver.com/prensa.aspx?orden=estudios

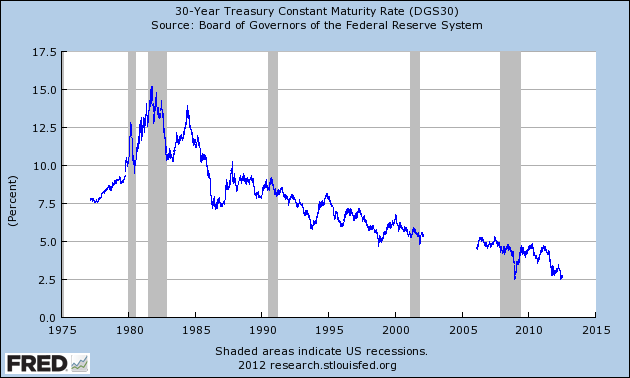

Note what Jim Grant says in the video interview, “The value that you see is the result of manipulated interest rates? We are in a BUBBLE of perceived “SAFE” Haven assets (think 30 years bonds at sub-2.5% or two year bonds at 0.003%)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mr-JHFmYT3o&feature=player_embedded

Posted in Economics & Politics, Investing Gurus, Risk Management

Tagged Ben Graham, Best Iver, James Grant, Leithner

Bubble Film (Documentary Trailer):

The characters in the documentary: Jim Grant, Jim Rogers, and many more… http://thebubblefilm.com/downloads/presskit.pdf

More here: http://www.tomwoods.com/

Who killed Kennedy?

I am not a conspiracy theorist (because the govt. is not competent to pull it off, but this is interesting.

http://www.economicpolicyjournal.com/2012/07/on-robert-wenzel-show-who-killed-jfk.html

Good articles here for students: http://www.oldschoolvalue.com/

Model of valuing stocks the Buffett way: http://www.aaii.com/computerized-investing/article/valuing-stocks-the-warren-buffett-way

How Morningstar measures moats http://news.morningstar.com/articlenet/article.aspx?id=91441&

One hundred things I have learned while investing (good read): http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2012/06/29/the-100-things-ive-learned-in-investing.aspx

An investment search process: http://www.jonesvillalta.com/process.php#anchor4

Valuation Models:Copy of Villalta_WebTool_APV and Copy of Villalta_WebTool_FCFE (see if these make sense to you or ignore)

Screening

http://blog.iii.co.uk/introducing-the-human-screen/

Investing articles: http://www.gannonandhoangoninvesting.com/

Watch MBAs present their value investing ideas to Pershing Square’s Bill Ackman at Columbia GBS: several videos links–just scroll down http://www7.gsb.columbia.edu/valueinvesting/events/pershing

More recordings/videos: Investment Lectures: (2012)http://www7.gsb.columbia.edu/valueinvesting/coursesfaculty/recordings

And even more…… http://www.bengrahaminvesting.ca/Resources/videos.htm

After decades of rising prices, hostile foreign suppliers and warnings that Americans will have to bicycle to work, the world faces the possibility of vast amounts of cheap, plentiful fuel. And the source for much of this new supply? The U.S.

After decades of rising prices, hostile foreign suppliers and warnings that Americans will have to bicycle to work, the world faces the possibility of vast amounts of cheap, plentiful fuel. And the source for much of this new supply? The U.S.

“If this is true, this could be another dominant American century,” said Brian Wesbury, chief economist at First Trust Advisors, money managers in Wheaton, Ill.

U.S. natural-gas production is growing 4% to 5% a year, driven by sharply higher shale gas output. Shale gas production is forecast at 7.609 trillion cubic feet this year, up 11.6% from 2011 and 12 times the 2004 level.

Are you a chimp? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u_9tZ3aPCFo&feature=relmfu

http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-04-12/how-to-play-the-market-irving-kahn

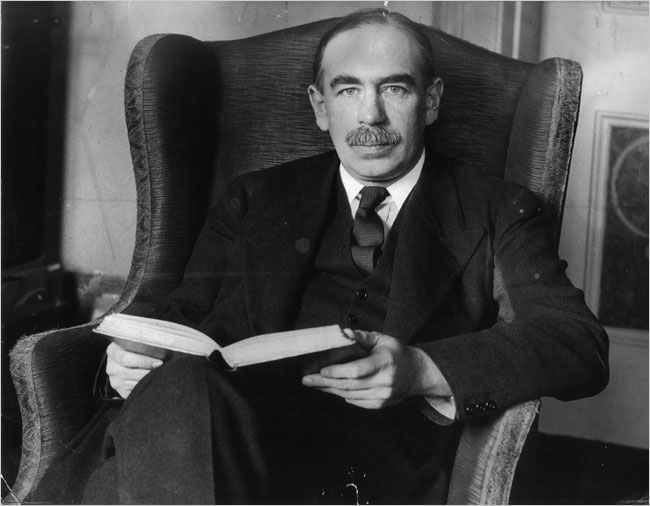

No two recoveries are alike. When I came to Wall Street in 1928, I thought the market was crazy. It hit the brakes in ’29. You have to be careful to distinguish between one recovery and the other. You stick to value, to Benjamin Graham, the man who wrote the bible for the market. It’s a mistake to believe you can do more, I warn you. John Maynard Keynes was one of the most famous economists in history. He was a genius, but he failed as a macro investor. It was hard to believe at the time. But when he became a bottom-up value guy, well, he became very successful. With value investing, you don’t have to bend the truth to accommodate periods with derivatives and manias. Value investing will almost always be right.

I’ve seen a lot of recoveries. I saw crash, recovery, World War II. A lot of economic decline and recovery. What’s different about this time is the huge amount of quote-unquote information. So many people watch financial TV—at bars, in the barber shop. This superfluity of information, all this static in the air.

There’s a huge number of people trading for themselves. You couldn’t do this before 1975, when commissions were fixed by law. It’s a hyperactivity that I never saw in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. A commission used to cost you a hell of a lot; you couldn’t buy and sell the same thing 16 times a day.

You say you feel a recovery? Your feelings don’t count. The economy, the market: They don’t care about your feelings. Leave your feelings out of it. Buy the out-of-favor, the unpopular. Nobody can predict the market. Take that premise to heart and look to invest in dollar bills selling for 50¢. If you’re going to do your own research and investing, think value. Think downside risk. Think total return, with dividends tiding you over. We’re in a period of extraordinarily low rates—be careful with fixed income. Stay away from options. Look for securities to hold for three to five years with downside protection. You hope you’re in a recovery, but you don’t know for certain. The recovery could stall. Protect yourself. — As told to Roben Farzad

Kahn Brothers Portfolio:http://www.gurufocus.com/StockBuy.php?GuruName=Irving+Kahn

Low interest rates and low volatility mean LEAPs MAY be a cheap, non-recourse loan for owning a growing business or a way to lower your over-all exposure without giving up returns.

Low interest rates and low volatility mean LEAPs MAY be a cheap, non-recourse loan for owning a growing business or a way to lower your over-all exposure without giving up returns.

Rising interest rates and volatility (all else being equal) will raise the price of your leap. If you believe a company will grow its intrinsic value 10% to 15% in the next 18 months to two years then leaps may be an attractive tool. Option traders’ models do not do as well as the cone of uncertainty increases (the time period until expiration is beyond a year).

A refresher on options:Options_Guide but the Bible on options is Options As a Strategic Investment by Lawrence G. McMillan. See Chapter 25, Leaps.

This blog discusses using Leaps for Cisco during 2011. http://www.valuewalk.com/2011/07/cisco-leaps-opportunity-lifetime/

I am not recommending that you agree, but follow the logic.

If you are new to investing then stay away, but for some, NOW may be a time to use this tool with the right company at the right price.

Good luck and be careful not to over-use options. Options, when you are successful, can become as addictive as crack–who doesn’t like making 10 times your money?

Background

Keynes’ famous Chapter 12 on speculation and the stock market (suggested reading by W. Buffett): Long-Term Expectations http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/economics/keynes/general-theory/ch12.htm

Relevance for today: A CDO Manager finds himself living in Chapter 12 of Keynes’ Chapter 12 of Keynes’ General Theory

Barry Ritholtz reprints a scary e-mail from a friend in the collaterized debt obligation business (don’t you have a friend in the CDO business?):

I was talking to CDO managers in mid-’05 that were saying how rich sub-prime MBS was and how wrong everyone was for buying that stuff at the spreads they were. To a man, they all agreed they were paying too much for the risk, they all believed that HPA [ED: home price appreciation] was going negative soon. But, sadly, they had to buy the stuff because they needed to accumulate collateral for their CDO issuance. F*&%, we all knew we were overpaying, even back in 2005. We knew it was essentially a bet that home price appreciation was going to continue at levels that couldn’t be sustained. No way that could keep going on.

So why did they keep buying?

The answer is quite simple: DEAL FEES. I gotta keep buying collateral, in order to keep issuing these transactions as a CDO manager. Its my job: I gotta keep accumulating collateral, and I gotta issue the liability against that collateral.

This is an important element of what’s called the “limits of arbitrage” (Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, Journal of Finance, March 1997) or “career risk” (Jeremy Grantham, in various investor letters) explanation for why markets get so crazy sometimes. Brad DeLong has pushed this argument lately in his blog, and I’d like to second his endorsement: The smart professionals we rely on to keep market prices sane (or “efficient”) sometimes face career incentives that make it almost impossible for them to act on their own rational judgments. The most famous and eloquent account of this can be found in Chapter 12 of John Maynard Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money:

Investment based on genuine long-term expectation is so difficult to-day as to be scarcely practicable. He who attempts it must surely lead much more laborious days and run greater risks than he who tries to guess better than the crowd how the crowd will behave; and, given equal intelligence, he may make more disastrous mistakes. There is no clear evidence from experience that the investment policy which is socially advantageous coincides with that which is most profitable. It needs more intelligence to defeat the forces of time and our ignorance of the future than to beat the gun. Moreover, life is not long enough; — human nature desires quick results, there is a peculiar zest in making money quickly, and remoter gains are discounted by the average man at a very high rate. The game of professional investment is intolerably boring and over-exacting to anyone who is entirely exempt from the gambling instinct; whilst he who has it must pay to this propensity the appropriate toll. Furthermore, an investor who proposes to ignore near-term market fluctuations needs greater resources for safety and must not operate on so large a scale, if at all, with borrowed money — a further reason for the higher return from the pastime to a given stock of intelligence and resources. Finally it is the long-term investor, he who most promotes the public interest, who will in practice come in for most criticism, wherever investment funds are managed by committees or boards or banks. For it is in the essence of his behaviour that he should be eccentric, unconventional and rash in the eyes of average opinion. If he is successful, that will only confirm the general belief in his rashness; and if in the short run he is unsuccessful, which is very likely, he will not receive much mercy. Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.

Read more: http://business.time.com/2007/08/24/a_cdo_manager_finds_himself_li/#ixzz20DMkgM8H

Keynes is considered one of the best all-time investors. Two academics analyze Keynes’ investment performance–link here:

Every 100 pounds Sterling would have grown to 1,675 – 22 years later. The same money invested in an index of UK stocks would have grown to 424 sterling. This during a period encompassing the Great Crash of 19129, the Great Depression, and the Second World War.

Keynes recognized the potential of an asset class no one wanted to invest in, equities. He took advantage of the many inefficiencies by concentrating in companies he knew best with bottom-up company-specific research. He focused his efforts and concentrated his positions. That approach sometimes left him taking a beating, suffering a 23% loss in 1938 when the stock market was down only 8.6%.

Keynes had a very rate quality. He never lost intellectual confidence needed to make contrarian investments. But he could see when he had made a mistake, deal with it, and modify his behaviour. Ironically, he ignored his macro-economic policies and forecasts which current economic policy makers can’t seem to do even after years of devastating effects.

A summary of the above academic paper is presented below.

Abstract: Keynes made a major contribution to the development of professional asset management. Combining archival research with modern investment analysis, we evaluate John Maynard Keynes’s investment philosophy, strategies, and trading record, principally in the context of the King’s College, Cambridge endowment. His portfolios were idiosyncratic and his approach unconventional. He was a leader among institutional investors in making a substantial allocation to the new asset class, equities. Furthermore, we decipher a radical change in Keynes’s approach to investment which was to the considerable benefit of subsequent performance. Overall, Keynes’s experiences in managing the endowment remain of great relevance to investors today.

Conclusion: This study of Keynes’ stock market investing offers both a reappraisal of his investment performance and an assessment of his contribution to professional asset management. The King’s College endowment permitted Keynes to give full expression to his investment abilities. We provide the first detailed analysis of his investment ability in terms of his management of the King’s portfolios. Previous studies had claimed that Keynes’s performance for his college was stellar. Our results, however, qualify this view. According to our event time analysis, the changing pattern of cumulative returns around his buy and sell decisions before and after the difficult early 1930s, provides evidence to substantiate Keynes’s own claims that he fundamentally overhauled his investment approach.

Essentially, he switched from a macro market-timing approach to bottom-up stock-picking. Furthermore, Keynes’s experience at King’s foreshadowed important developments in modern investment practice on several dimensions.

Firstly, his strategic allocation to equities was path-breaking. Not until the second half of the twentieth century did institutional fund managers follow his lead. His aggressive purchase of equities pushed the common stock weighting of the whole endowment’s security portfolio over 50% by the 1940s. This was as dramatic and far-sighted a change in the investment landscape as the shift to alternative assets in more recent times.

Secondly, his willingness to take a variety of risks in the King’s portfolio and to depart dramatically both from the market and institutional consensus exemplifies the opportunity available to long-term investors such as endowments to be unconventional in their portfolio choices.

Thirdly, the contrast between the receptive environment at King’s and the conditions he faced at other institutions reminds us of how critical, conditional on possessing investment talent, is the right organizational set-up. Talent alone is not enough. Equally, his achievements underscore the main finding of Lerner, Schoar, and Wang (2008) in their analysis, two generations later, of the leading Ivy League endowments that such idiosyncratic investment approaches are very difficult for the vast majority of managers to replicate.

Editor of CSInvesting: I may think of Keynesian Economics as daft (http://archive.mises.org/5833/the-failure-of-the-new-economics/), but we can all learn from this investor.