“If a man has a talent and cannot use it, he has failed. If he has a talent and uses only half of it, he has partly failed. If he has a talent and learns somehow to use the whole of it, he has gloriously succeeded, and won a satisfaction and a triumph few men ever know.” — Thomas Wolfe

“Work is love made visible. And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy.” –Kahlil Gibran

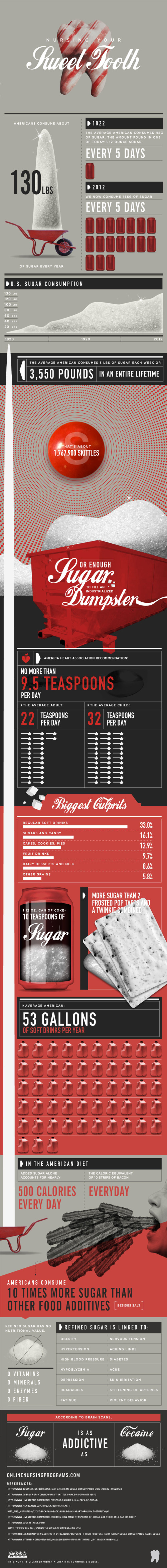

SUGAR: last mentioned http://wp.me/p1PgpH-1dr. Have a jelly donut:http://youtu.be/OhhJwJbYruA

The Future?

A day made of glass: Part 1: http://youtu.be/6Cf7IL_eZ38 Part 2: http://youtu.be/jZkHpNnXLB0

See’s Candies last discussed here: http://wp.me/p1PgpH-1bZ.

Readers did a fine job of analyzing why Buffett paid 3xs tangible book value. While cleaning out old files I came across a discussion of See’s that perhaps not many have seen, so I will post tomorrow.

What is Wrong with the Austrians?

Before you can know what is “wrong” with Austrian Business Cycle Theory (“ABCT”), you need to know about the theory.

A ten lecture series on Austrian Economic Analysis: http://mises.org/media/categories/89/Introduction-to-Austrian-Economic-Analysis

The Austrian School: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austrian_School

As a history fanatic, I am enjoying A Nation of Deadbeats: An Uncommon History of America’s Financial Disasters by Scott Reynolds Nelson.

More on the author here:http://www.wm.edu/research/ideation/social-sciences/economic-deja-vu6543.php

The book’s author has studied the Austrian approach but finds fault with it. He weaves an interesting account of the Panics of 1792, 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1907, 1920 and 1929. He says government can’t be entirely to blame for some of the overleveraging, fraud and mal-investment of the booms that lead to busts. I lack historical knowledge to completely grasp his arguments, but after finishing this book I will take another crack. I do believe that understanding where leverage has built up is crucial to understanding the effects of the bust. For example, the Internet boom occurred mostly in equities while the 2008 credit crisis developed in the banking system. Banking panics will most likely be much more severe due to the high (at least 10 to 1) leverage in our banking system. The credit contraction is quick to spread throughout the economy. The Internet bust primarily caused a bust in Internet and Telcom companies’ stock prices.

The Panic of 1873 as a model to understand 2008

The best model to understand the 2008 Crisis was the 1873 panic NOT 1929.

The author: “Everyone was talking about 1929, but I said in this article that the depression following the Panic of 1873 was much more like our current crash than 1929,” Nelson said. “1873 was a mortgage meltdown, then bank failure, which then led to stock market collapse.”

http://srnels.people.wm.edu/articles/realGrtDepr.html

Scott Nelson 1873 and 2008 and below are original source documents from the period. NYT on Panic of 1873,

Workers Riot in NYC 1874

Speculation Rampant in RR in 1873

Problems with Austrian Business Cycle Theory

Another historian’s view: Jeffrey Hummel Arguments against ABCT

I will seek out the contra-arguments to Austrian theory as a way to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of various economic theories and approaches. Is Austrian theory perfect? I don’t believe so, but it has been the best construct for me to understand how booms develop and end–so far. What do YOU think?

Business cycle theory

According to most mainstream economists, the Austrian business cycle theory is incorrect.[33]

Some mainstream economists argue that the Austrian business cycle theory requires bankers and investors to exhibit a kind of irrationality, because their theory requires bankers to be regularly fooled into making unprofitable investments by temporarily low interest rates.[5][24][117] In response, historian Thomas Woods argues that few bankers and investors are familiar enough with the Austrian business cycle theory to consistently make sound investment decisions. Austrian economists Anthony Carilli and Gregory Dempster argue that a banker or firm loses market share if it does not borrow or loan at a magnitude consistent with current interest rates, regardless of whether rates are below their natural levels. Thus businesses are forced to operate as though rates were set appropriately, because the consequence of a single entity deviating would be a loss of business.[95] Austrian economist Robert Murphy argues that it is difficult for bankers and investors to make sound business choices because they cannot know what the interest rate would be if it were set by the market.[97] Austrian economist Sean Rosenthal argues that widespread knowledge of the Austrian business cycle theory increases the amount of malinvestment during periods of artificially low interest rates.[118]

Economist Paul Krugman has argued that the theory cannot explain changes in unemployment over the business cycle. Austrian business cycle theory postulates that business cycles are caused by the misallocation of resources from consumption to investment during “booms”, and out of investment during “busts”. Krugman argues that because total spending is equal to total income in an economy, the theory implies that the reallocation of resources during “busts” would increase employment in consumption industries, whereas in reality, spending declines in all sectors of an economy during recessions. He also argues that according to the theory the initial “booms” would also cause resource reallocation, which implies an increase in unemployment during booms as well.[28] In response, Austrian economist David Gordon argues that Krugman’s argument is dependent on a misrepresentation of the theory. He furthermore argues that prices on consumption goods may go up as a result of the investment bust, which could mean that the amount spent on consumption could increase even though the quantity of goods consumed has not.[119] Furthermore, Roger Garrison argues that a false boom caused by artificially low interest rates would cause a boom in consumption goods as well as investment goods (with a decrease in “middle goods”) thus explaining the jump in unemployment at the end of a boom.[120] Many Austrians also argue that capital allocated to investment goods cannot be quickly augmented to create consumption goods.[121]

Economist Jeffery Hummel is critical of Hayek’s explanation of labor asymmetry in booms and busts. He argues that Hayek makes peculiar assumptions about demand curves for labor in his explanation of how a decrease in investment spending creates unemployment. He also argues that the labor asymmetry can be explained in terms of a change in real wages, but this explanation fails to explain the business cycle in terms of resource allocation.[122]

Hummel also argues that the Austrian explanation of the business cycle fails on empirical grounds. In particular, he notes that investment spending remained positive in all recessions where there are data, except for the Great Depression. He argues that this casts doubt on the notion that recessions are caused by a reallocation of resources from industrial production to consumption, since he argues that the Austrian business cycle theory implies that net investment should be below zero during recessions.[122] In response, Austrian economist Walter Block argues that the misallocation during booms does not preclude the possibility of demand increasing overall.[123]

Critics have also argued that, as the Austrian business cycle theory points to the actions of fractional-reserve banks and central banks to explain the business cycles, it fails to explain the severity of business cycles before the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913.[33] Supporters of the Austrian business cycle theory respond that the theory applies to the expansion of the money supply, not necessarily an expansion done by a central bank.[124] Historian Thomas Woods argues that the crashes were caused by various privately-owned banks with state charters that issued paper money, supposedly convertible to gold, in amounts greatly exceeding their gold reserves.[125]

In 1969, economist Milton Friedman, after examining the history of business cycles in the U.S., concluded that “The Hayek-Mises explanation of the business cycle is contradicted by the evidence. It is, I believe, false.”[26] He analyzed the issue using newer data in 1993, and again reached the same conclusion.[27] Austrian economist Jesus Huerta de Soto argued that Friedman’s conclusions are based on misleading data (such as GDP).[124] Austrian economist Roger Garrison argued that Friedman misinterpreted economic aggregates and how they related to the business cycles he reviewed.[126]

END

I have been finally approved as a kidney donor so I wait for the date of my surgery. More blood samples, CAT scans and X-rays have been taken of me than any lab rat. Ready to go so the recipient doesn’t have to suffer dialysis or death.

I have been finally approved as a kidney donor so I wait for the date of my surgery. More blood samples, CAT scans and X-rays have been taken of me than any lab rat. Ready to go so the recipient doesn’t have to suffer dialysis or death.