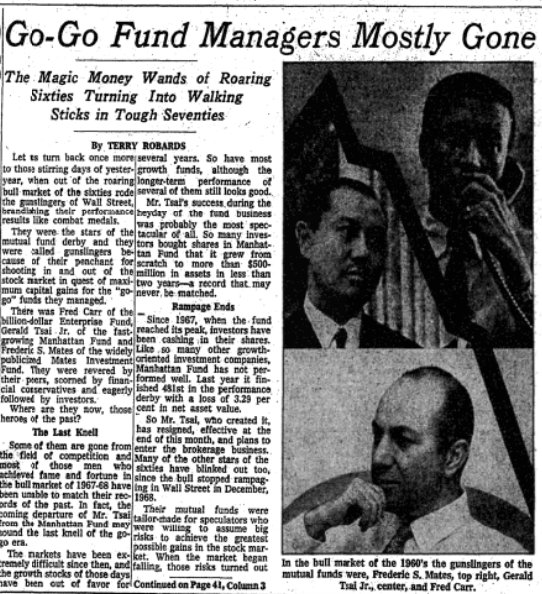

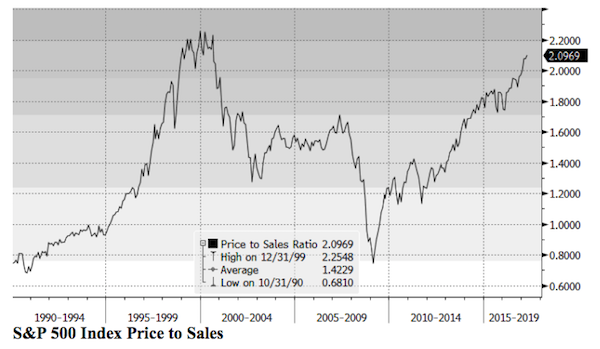

May 8, 2017This Time is Not Different, Because This Time is Always Different “History repeats – the argument for abandoning prevailing valuation methods regularly emerges late in a bull market, and typically survives until about the second down-leg (or sufficiently hard first leg) of a bear. Such arguments have included the ‘investment company’ and ‘stock scarcity’ arguments in the late 20’s, the ‘technology’ and ‘conglomerate’ arguments in the late 60’s, the nifty-fifty ‘good stocks always go up’ argument in the early 70’s, the ‘globalization’ and ‘leveraged buyout’ arguments in 1987 (and curiously, again today), and the ‘tech revolution’ and ‘knowledge-based economy’ arguments in the late 1990’s. Speculative investors regularly create ‘new era’ arguments and valuation metrics to justify their speculation.” – John P. Hussman, Ph.D., New Economy or Unfinished Cycle?, June 18, 2007. The S&P 500 would peak just 2% higher in October of that year, followed by a collapse of more than -55%. “Old ways of valuing stocks are outdated. A technological revolution has created opportunities for continued low inflation, expanding profits and rising productivity. Thanks to these factors, the United States may be able to enjoy an extended period of expanding stock prices. Jumping out now would leave you poorer than you might become if you have some faith.” – Los Angeles Times, May 11, 1999. While it’s tempting to counter that the S&P 500 would rise by more than 12% to its peak 10 months later, it’s easily forgotten that the entire gain was wiped out in the 3 weeks that followed, moving on to a 50% loss for the S&P 500 and an 83% loss for the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100.. “Stock prices returned to record levels yesterday, building on the rally that began in late trading on Wednesday… ‘It’s all real buying’ [said the head of index futures at Shearson Lehman Brothers], ‘The excitement here is unbelievable. It’s steaming.’ The continuing surge in American stock prices has produced a spate of theories. [The] chief economist of Kemper Financial Services Inc. in Chicago argued in a report that, contrary to common opinion, American equities may not be significantly overpriced. For one thing, [he] said, ‘The market may be discounting a far-larger rise in future corporate earnings than most investors realize is possible, [and foreign investment] may be altering the traditional valuation parameters used to determine share-price multiples.’ He added, ‘It is quite possible that we have entered a new era for share price evaluation.’” – The New York Times, August 21, 1987 (the S&P advanced by less than 1% over the next 3 sessions, and then crashed) “The failure of the general market to decline during the past year despite its obvious vulnerability, as well as the emergence of new investment characteristics, has caused investors to believe that the U.S. has entered a new investment era to which the old guidelines no longer apply. Many have now come to believe that market risk is no longer a realistic consideration, while the risk of being underinvested or in cash and missing opportunities exceeds any other.” – Barron’s Magazine, February 3, 1969. The bear market that had already quietly started in late-1968 would take stocks down by more than one-third over the next 18 months, and the S&P 500 Index would stand below its 1968 peak even 14 years later. “The ‘new-era’ doctrine – that ‘good’ stocks (or ‘blue chips’) were sound investments regardless of how high the price paid for them — was at bottom only a means for rationalizing under the title of ‘investment’ the well-nigh universal capitulation to the gambling fever.” – Benjamin Graham & David Dodd, Security Analysis, 1934, following the 1929-1932 collapse “The recent collapse is the climax, but not the end, of an exceptionally long, extensive and violent period of inflation in security prices and national, even world-wide, speculative fever. This is the longest period of practically uninterrupted rise in security prices in our history… The psychological illusion upon which it is based, though not essentially new, has been stronger and more widespread than has ever been the case in this country in the past. This illusion is summed up in the phrase ‘the new era.’ The phrase itself is not new. Every period of speculation rediscovers it.” – Business Week, November 1929. The market collapse would ultimately exceed -80%. See http://hussmanfunds.com/wmc/wmc170508.htm Referred to: This time seems very very different Grantham This time is not different, because this time is always different. Throwing in the towel When a boxer is taking a beating, to avoid further punishment, a towel is sometimes thrown from the corner as a token of defeat. Yet even after the towel is thrown, a judicious referee has the right to toss the towel back into the corner and allow the fight to continue. For decades, Jeremy Grantham, a value investor whom I respect tremendously, has championed the idea, recognized by legendary value investors like Ben Graham, that current profits are a poor measure of long-term cash flows, and that it is essential to adjust earnings-based valuation measures for the position of profit margins relative to their norms. In Grantham’s words, “Profit margins are probably the most mean-reverting series in finance, and if profit margins do not mean-revert, then something has gone badly wrong with capitalism.” He learned this lesson early on, during the collapse that followed the go-go years of the late-1960’s. Grantham once described his epiphany: “I got wiped out personally in 1968, which was the last really crazy, silly stock market before the Internet era… I became a great reader of history books. I was shocked and horrified to discover that I had just learned a lesson that was freely available all the way back to the South Sea Bubble.” In recent weeks, Grantham has essentially thrown in the towel, suggesting “this time is decently different”: “Stock prices are held up by abnormal profit margins, which in turn are produced mainly by lower real rates, the benefits of which are not competed away because of increased monopoly power… In conclusion, there are two important things to carry in your mind: First, the market now and in the past acts as if it believes the current higher levels of profitability are permanent; and second, a regular bear market of 15% to 20% can always occur for any one of many reasons. What I am interested in here is quite different: a more or less permanent move back to, or at least close to, the pre-1997 trends of profitability, interest rates, and pricing. And for that it seems likely that we will have a longer wait than any value manager would like (including me).” I’ve received a flurry of requests for my views on Grantham’s shift. My simple response is to very respectfully toss Grantham’s towel back into the corner. Here’s why. First, Grantham argues that much of the benefit to margins is driven by lower real interest rates. The problem here is two-fold. One is that the relationship between real interest rates and corporate profit margins is extremely tenuous in market cycles across history. Second, the fact is that debt of U.S. corporations as a ratio to revenues is more than double its historical median, leaving total interest costs, relative to corporate revenues, no lower than the post-war norm. |

—

The last three months of 1999 were just about the sickest thing I’d ever seen. It was an orgy, but I simply couldn’t bring myself to buy a stock that was up $10m, hoping it would go up $15, even though it was overvalued by $100. But by choosing to sit out most of the ramp, determined to wait for the inevitable implosion, I was the Greatest Fool of All, as those around me made mind-numbing profits as, day after day. YHOO, AMZN and CGMI would gap $10 a day, immune to gravity as the Nazz, aka NASDAQ, ripped right past 3000 and didn’t even blink rocketing past 4,000. At the end of the year, the Nazz was up 83 percent, a far cry from the 5 to 7 percent stocks had returned historically. People were too busy celebrating and shouting “It’s different this time.” to realize such an adjustment was unsustainable. It is like a guy who averages five home runs a year suddenly hitting fifty. Something is not right in Mudville. —Confessions of a Wall Street Insider: A Cautionary Tale of Rats, Feds, And Banksters by Michael Kimelman

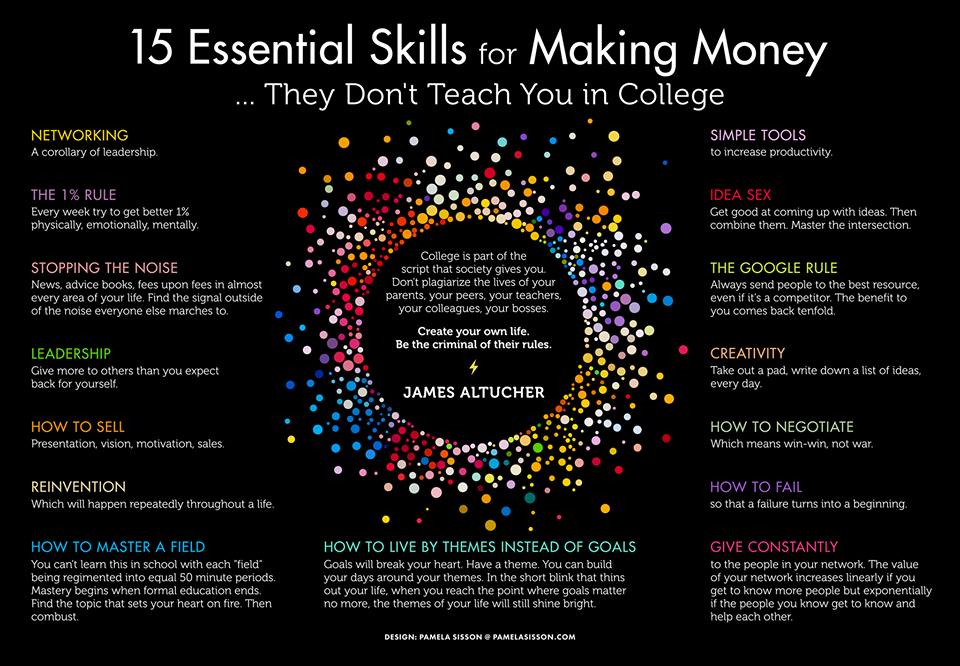

Expanding your circle of competence-Platforms and Networks

Note what Prof. Greenwald says about Amazon and Apple. If Apple is JUST a product company then I would agree, but what if Apple has network effects with its music and iPods for example?

http://csinvesting.org/2016/09/15/amazon-is-disappearing-says-prof-greenwald-of-columbia-gbs/

https://www.gurufocus.com/news/204202/professor-greenwald-thinks-apple-can-go-sonys-or-nokias-way

Don’t take expert opinion without heavily salted skepticism. What do YOU think?

SHORTING the FANGS: http://www.businessinsider.com/fang-stocks-have-cost-short-sellers-this-year-2017-5 How do you value a company with almost $0 (zero) marginal costs?

We will delve deeper in the next post.

PS: info@Santangels.com to sign up for value investing info.